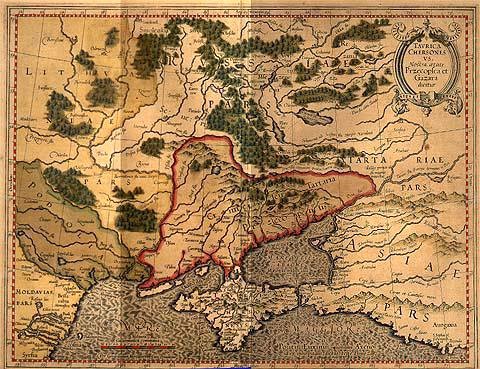

4. Gerard Mercator. 1595. Ukraine, Russia, Tartaria.

На карте Тартария находится на землях казаков.

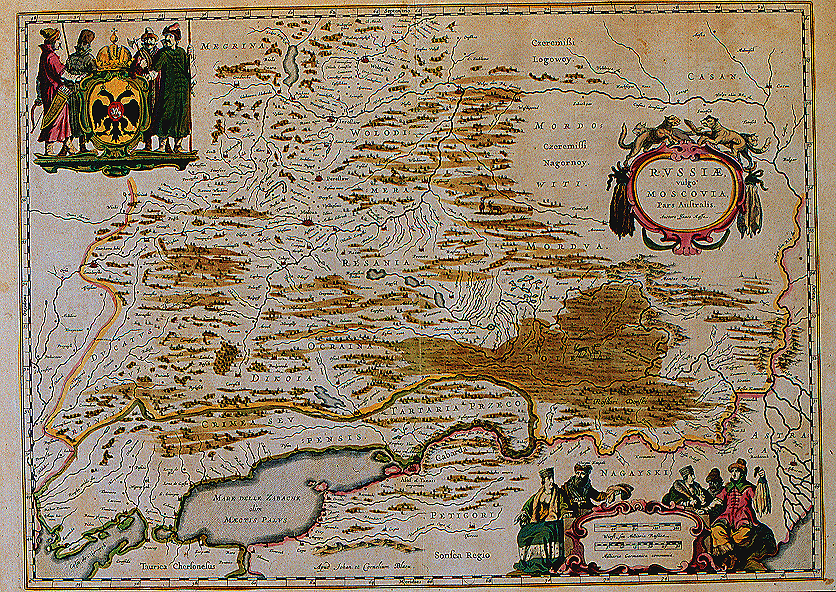

5. Isaac Massa. 1620. Russiae vulgo Moscovia, Pars Australis, Paris.

Над рекой Дон выделена область с названием Pole. На карте в п. З здесь была Тартария. Pole есть и на карте 1678 года, причем чуть выше живут татары.

From the Atlas of Johannes and Cornelius Blaeu. The figures at the bottom are dressed in furs, reflecting the contemporary interest in Russia as a fur-producing region.

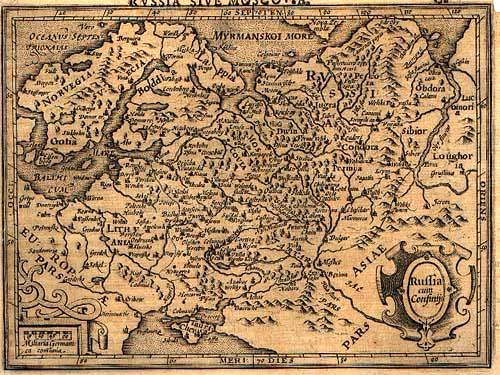

6. Mercator. Russia. 1621. Avery early map of European Russia.

Тартария на Дону, Готия в Швеции.

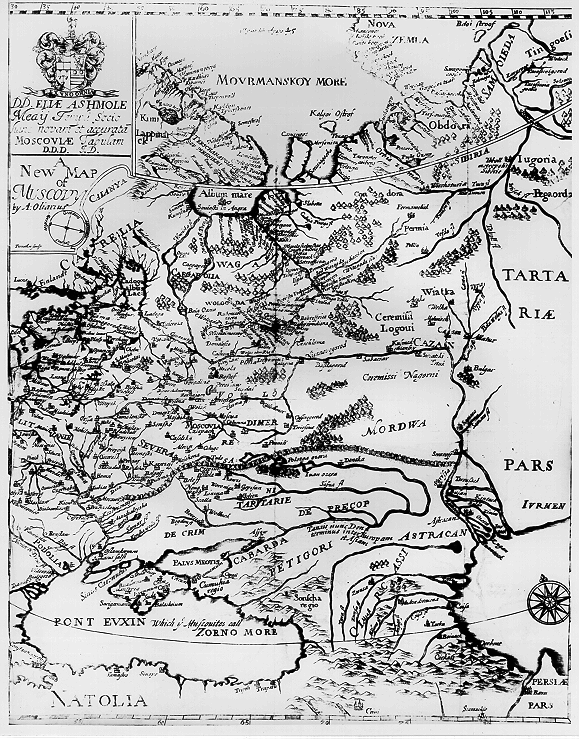

7. Olearius, Adam 1669. A new map of Muscovy.

На землях донских казаков живут перикопские татары.

The voyages and travels of the ambassadors sent by Frederic Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy and the King of Persia. London, For John Starkey and Thomas Basset, 1669.

Olearius was secretary to the embassy sent out by the duke of Holstein in 1633 to explore commercial opportunities in Persia and Russia. This map portrays much of the area traversed by the embassy, showing western Russia from the Murmansk to the Black and Caspian Seas, the river systems being dominant features.

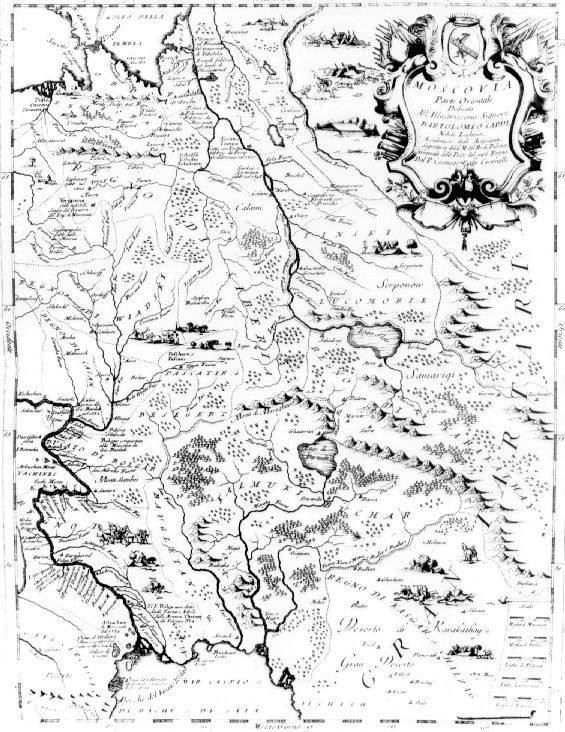

8. Coronelli, Vincenzo. 1690.

Сибирь между Волгой и Уралом, Великая Тартария, Regno di Kasgak Chaizag (?)).

Atlante Veneto, nel quale si contiene la descrittione geografica, storica, sacra, profana, e politica. Venice, Domenico Padoueani, 1690. This map includes that part of Russia north of the Caspian Sea and somewhat to the east.

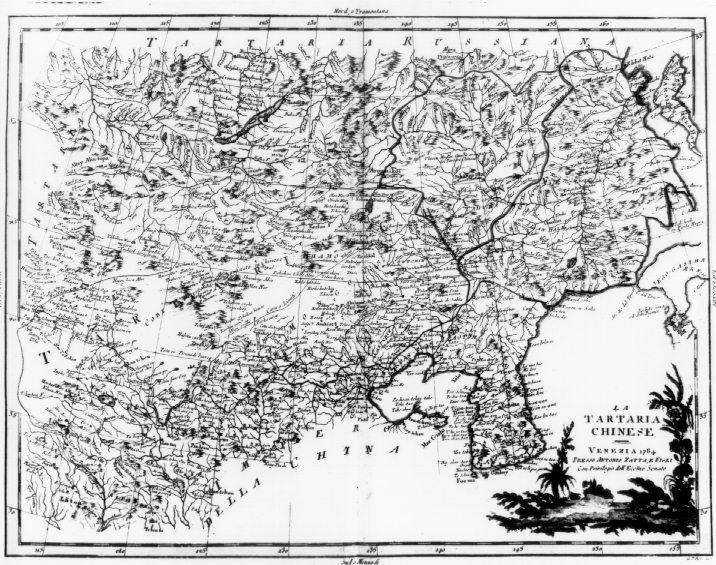

9. Zatta, Antoneo. 1779–85. Китайская Тартария.

Zatta is not well known as a map publisher although his four-volume atlas contains 214 maps. They are distinguished more for their clarity and artistic quality than for originality. Two of the maps portray Asiatic Russia including this one of Independent Tartary which was nominally a part of the Russian empire

10. Другие карты.

Moscovia.1621 — http://users.univer.omsk.su/~guts/History/Mercator_Moscovy1621.jpg (89 K).

Russia 1651 — http://users.univer.omsk.su/~guts/History/russ1651.gif (407 K)

Russia 1678 — http://users.univer.omsk.su/~guts/History/russ1678.gif (357 K)

Crim http://users.univer.omsk.su/~guts/History/crim17xx.gif (441K)

Tartaria 1570 — http://users.univer.omsk.su/~guts/History/tartar1570.GIF (469 K)

Tartaria 1600 — http://users.univer.omsk.su/~guts/History/asia1600.gif (888 K)

Tartaria 1612 — http://users.univer.omsk.su/~guts/History/asia1612.gif (387 K)

Tartaria 1660 — http://users.univer.omsk.su/~guts/History/tart1660.gif (434 K)

И это далеко не полный перечень. Таким образом, западные европейцы старательно составляли карты России и тиражировали их. Но в самой России это предприятие «не имело успеха», несмотря на указания царей. Хотя если вспомнить о «дивных» сибирских находках В. Н. Татищева, то следует предположить, что карты все-таки выпускались (из слов Татищева трудно понять, печатные это карты или ручной работы). Но затем карты «исчезали сами собой».

Что можно сказать о западноевропейских старых картах России? Фактически два основных обстоятельства становятся заметными:

• разделяются Московия и Тартария; последняя расположена и в Европе, и в Азии в степных зонах (стоит заметить, что еще в XVII в. Азия начиналась от Дона и Волги, т. е. Тартария — азиатская страна, но при этом были и «татарове европския» (Лызлов, 1990. С. 8));

• Тартария захватывает в XVII в. донские земли, где уже вроде как давно живут донские казаки.

Наконец, полезно привести мнение В. Н. Татищева о западноевропейских картах: «…все в Германии и Голандии печатанные ландкарты руские неисправны и, сколько я оных имею, все негодны, кроме Страленбергом, а потом Генсием поправленной, и с описанием весьма неисправным изданых, в которых нечто ближе к истинне находится, да сие им в вину причесть неможно, потому что правильных ихвестий получить не могут, да и мы сами никакого достаточного и правильного пределов описания не имеем» (Татищев, Т. 1. С. 346). Кстати, Страленберг — швед, долго находившийся в русском плену. Вернулся он на родину лишь в 1722 году.

Карты в древней России называли чертежами. Карта имеет военное значение. Поэтому, без всякого сомнения, чертежи в России делали! Где же они? «В результате многолетних поисков в различных картохранилищах, архивах, библиотеках удалось выявить и описать 935 русских географических чертежей. К этому числу можно прибавить еще 238 учтенных чертежей сибиряка С. У. Ремизова, созданных в период с. 1697 по 1730 г.» (Кусов, с. 7). Причем самый ранний чертеж относиться к 1536 г. Увы, это всего лишь план участка земли вдоль реки. В архивах есть упоминания в многочисленных древних чертежах XV–XVII вв. (Кусов, с. 6–7; Рыбаков, 1974). Но все карты, по которым можно было бы ознакомиться с Русью и ее соседями исчезли. Мы ничего не можем сказать об Орде, ее городах и территории. Не потому ли карты исчезли? Думается, что их уничтожили или спрятали, причем очень далеко. Но рано или поздно мы о них еще услышим.

В Англии в 1983 г. вышла книга «Древние карты», авторы которой также не могут назвать каких-либо древних русских карт, более ранних, чем «Большой чертеж». Ниже мы приводим соответствующий фрагмент из этой английской книги в том виде, как он опубликован в Интернете:

Antique Maps by Carl Moreland and David Bannister

Phaidon Press Limited, London,

Originally published by Longman 1983

Third edition 1989. First paperback edition 1993

http://www.antiquemaps.со.uk/book/chapterl9.html

RUSSIA

It is scarcely necessary to look at a map of Russia — with which we must include Siberia — to visualize the daunting task facing Russian map makers. Indeed, considering the vastness of their territory and the lack of skilled cartographers, it is surprising that relatively good maps were available for engraving and printing in most of the well known sixteenth and seventeenth century atlases. Generally, maps of that time were based on material brought back from Moscow by visitors from the West. Notable among these were the following:

PAOLO GIOVIO (1483–1552)

Map of European Russia (1525) based on detail provided by a Muscovite ambassador to Rome, Demetrius Gerasimov (c. 1465 — c. 1525). It appeared in manuscript form and was subsequently used by Giacomo Gastaldi in his 1548 edition of Ptolemy's Geographia and also by later publishers.

SIGISMUND HERBERSTEIN (1486–1566)

Map of Muscovia (1549) compiled by Herberstein, who was ambassador from the Habsburg Emperor, Maximilian I to Moscow. The map, based on material by a Lithuanian, Ivan Lyatsky fl. c. 1526–1555) was used by Sebastian Munster and others. Lyatsky himself also produced a map of Russia dated 1555.

ANTHONY JENKINSON (fl. 1545–1577)

The first English ambassador to Russia, Jenkinson made a remarkable journey as far as Bokhara in Asiatic Russia and subsequently compiled a famous map of his travels. Unfortunately, no actual copy of the map has survived but it was used by Ortelius in 1570 and Gerard de Jode in 1578 as the basis for maps in their atlases.

ISAAC MASSA (1587–1635)

A Dutch traveller, Massa compiled a map of Russia (c. 1612) which was used in the Blaeu/Jansson atlases.

CORNELIS CRUYS (1657–1727)

A Dutch Admiral, in the service of Peter the Great, compiled and published an atlas of the River Don and the Sea of Asov (c. 1704).

The first map of any real importance known to have been produced in Russia was the manuscript 'Great Map' compiled in the time of Tsar Boris Godunov (1598–1605), followed by later versions covering the expansion of the Empire southwards and eastwards. In the second half of the seventeenth century a start was made on the mapping of Siberia (1667) by Peter Godunov (fl. 1667–69) and an atlas of Siberia was published (c. 1698–1701) by Semyon Ulanovitch Remezov (1642–1720). Evidently the printing of maps in Russia presented difficulties which Peter the Great (1689–1725) attempted to overcome by licensing a Dutch publisher in Amsterdam specifically to print Russian maps. This was about 1699 but soon afterwards a private printing house was established in Moscow by the cartographer, Vasily Kiprianov (fl. 1706–17) who published maps of Russia and the World.

Plate: R.and J. OTIENS / JOH. CASPAR SCHEUCHZER Het Konink-ryk Japan Amsterdam (1728) c. 1740. Based on a work by the Swiss scholar Scheuchzer, this map is one of the few to use Japanese names as well as their westernized forms.

During this same period, Peter the Great ordered a comprehensive survey of his country and the training of a corps of professional surveyors. In charge of this immense undertaking was an employee of the State Chancellry, Ivan Kyrilov (1689–1737). He planned a 3 volume atlas of Imperial Russia to consist of something like 300 to 400 maps, but it soon became evident that advice and assistance by foreign cartographers was required if the project was to be completed in a reasonable time. In consequence, following a visit to France by the Tsar and the subsequent founding of the Imperial Academy of Sciences in 1724, the French cartographers Joseph Nicolas and Louis Delisle (brothers of Guillaume Delisle) were invited to St Petersburg to set up a School of Astronomy and to train teams of surveyors. Unfortunately, Kyrilov and the De-lisles totally disagreed on the methods of surveying needed to map the country and, in the event, Kyrilov pursued his own course and, in 1734, published the first part of his planned atlas consisting of a general map of Russia and 14 regional maps. Meanwhile, the Delisles travelled throughout Russia and Siberia gathering geographical data, compiling maps with the assistance of Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler (1707–83) and the Danish explorer Vitus Joh. Bering (1680–1741) who traversed Siberia on at least two occasions and explored the Northern Pacific. No doubt the Delisles also used much of Kyri-lov's material for, after Kyrilov's death in 1737, his atlas was suppressed, possibly because of inaccuracies but more likely as a result of jealousies and intrigue; only two copies of the atlas are known to exist. Eventually, in 1745, following further disagreements between Joseph Nicolas Delisle (who felt the work was still incomplete) and the Academy of Sciences the Atlas Russicus was published containing a general map and 19 regional maps. Thereafter, further work and revision of the atlas was in the hands of Michael Lomonosov (1711–65), director of the Geographical Department of the Academy. In due course, as in so many countries, official mapping was taken over by the military and, in 1816, a new survey by triangulation was undertaken, which eventually included Poland, most of which country was then occupied by Russia.