Paul Rusesabagina, Tom Zoellner

An Ordinary Man

To all the victims of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide,

to their widows and orphans, to the survivors.

To Tatiana, my wife and right hand;

to Lys, Roger, Diane and Tresor Rusesabagina

as well as Anaise and Carine Karimba.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Kathryn Court, Jill Kneerim, Alexis Washam, and Paul Buckley for their invaluable assistance in the production of this book.

“Many fledging moralists in those days were going about our town proclaiming that there was nothing to be done about it and we should bow to the inevitable. And Tarrou, Rieux, and their friends might give one answer or another, but its conclusion was always the same, their certitude that a fight must be put up, in this way or that, and there must be no bowing down. The essential thing was to save the greatest possible number of persons from dying and being doomed to unending separation. And to do this there was only one resource: to fight the plague. There was nothing admirable about this attitude; it was merely logical.”

– From The Plague, by Albert Camus

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This is a work of nonfiction. All of the people and events described herein are true as I remember them. For legal and ethical reasons, I have given pseudonyms to a handful of private Rwandan citizens. Each time this is done, the change is noted in the text.

Paul Rusesabagina

INTRODUCTION

My name is Paul Rusesabagina. I am a hotel manager. In April 1994, when a wave of mass murder broke out in my country, I was able to hide 1, 268 people inside the hotel where I worked.

When the militia and the Army came with orders to kill my guests, I took them into my office, treated them like friends, offered them beer and cognac, and then persuaded them to neglect their task that day. And when they came back, I poured more drinks and kept telling them they should leave in peace once again. It went on like this for seventy-six days. I was not particularly eloquent in these conversations. They were no different from the words I would have used in saner times to order a shipment of pillowcases, for example, or tell the shuttle van driver to pick up a guest at the airport. I still don’t understand why those men in the militias didn’t just put a bullet in my head and execute every last person in the rooms upstairs but they didn’t. None of the refugees in my hotel were killed. Nobody was beaten. Nobody was taken away and made to disappear. People were being hacked to death with machetes all over Rwanda, but that five-story building became a refuge for anyone who could make it to our doors. The hotel could offer only an illusion of safety, but for whatever reason, the illusion prevailed and I survived to tell the story, along with those I sheltered. There was nothing particularly heroic about it. My only pride in the matter is that I stayed at my post and continued to do my job as manager when all other aspects of decent life vanished. I kept the Hotel Mille Collines open, even as the nation descended into chaos and eight hundred thousand people were butchered by their friends, neighbors, and countrymen.

It happened because of racial hatred. Most of the people hiding in my hotel were Tutsis, descendants of what had once been the ruling class of Rwanda. The people who wanted to kill them were mostly Hutus, who were traditionally farmers. The usual stereotype is that Tutsis are tall and thin with delicate noses, and Hutus are short and stocky with wider noses, but most people in Rwanda fit neither description. This divide is mostly artificial, a leftover from history, but people take it very seriously, and the two groups have been living uneasily alongside each other for more than five hundred years.

You might say the divide also lives inside me. I am the son of a Hutu farmer and his Tutsi wife. My family cared not the least bit about this when I was growing up, but since bloodlines are passed through the father in Rwanda, I am technically a Hutu. I married a Tutsi woman, whom I love with a fierce passion, and we had a child of mixed descent together. This type of blended family is typical in Rwanda, even with our long history of racial prejudice. Very often we can’t tell each other apart just by looking at one another. But the difference between Hutu and Tutsi means everything in Rwanda. In the late spring and early summer of 1994 it meant the difference between life and death.

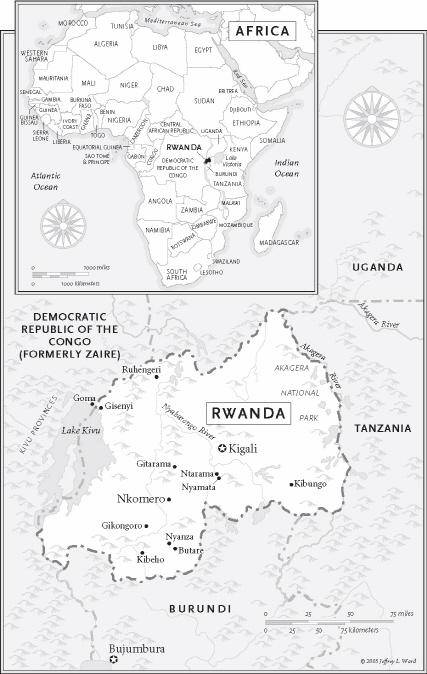

Between April 6, when the plane of President Juvenal Habyarimana was shot down with a missile, and July 4, when the Tutsi rebel army captured the capital of Kigali, approximately eight hundred thousand Rwandans were slaughtered. This is a number that cannot be grasped with the rational mind. It is like trying-all at once-to understand that the earth is surrounded by billions of balls of gas just like our sun across a vast blackness. You cannot understand the magnitude. Just try! Eight hundred thousand lives snuffed out in one hundred days. That’s eight thousand lives a day. More than five lives per minute. Each one of those lives was like a little world in itself. Some person who laughed and cried and ate and thought and felt and hurt just like any other person, just like you and me. A mother’s child, every one irreplaceable.

And the way they died… I can’t bear to think about it for long. Many went slowly from slash wounds, watching their own blood gather in pools in the dirt, perhaps looking at their own severed limbs, oftentimes with the screams of their parents or their children or their husbands in their ears. Their bodies were cast aside like garbage, left to rot in the sun, shoveled into mass graves with bulldozers when it was all over. It was not the largest genocide in the history of the world, but it was the fastest and most efficient.

At the end, the best you can say is that my hotel saved about four hours’ worth of people. Take four hours away from one hundred days and you have an idea of just how little I was able to accomplish against the grand design.

What did I have to work with? I had a five-story building. I had a cooler full of drinks. I had a small stack of cash in the safe. And I had a working telephone and I had my tongue. It wasn’t much. Anybody with a gun or a machete could have taken these things away from me quite easily. My disappearance-and that of my family-would have barely been noticed in the torrents of blood coursing through Rwanda in those months. Our bodies would have joined the thousands in the east-running rivers floating toward Lake Victoria, their skins turning white with water rot.

I wonder today what exactly it was that allowed me to stop the killing clock for four hours.

There were a few things in my favor, but they do not explain everything. I was a Hutu because my father was Hutu, and this gave me a certain amount of protection against immediate execution. But it was not only Tutsis who were slaughtered in the genocide; it was also the thousands of moderate Hutus who were suspected of sympathizing with or even helping the Tutsi “cockroaches”. I was certainly one of these cockroach-lovers. Under the standards of mad extremism at work then I was a prime candidate for a beheading.

Another surface advantage: I had control of a luxury hotel, which was one of the few places during the genocide that had the image of being protected by soldiers. But the important word in that sentence is image. In the opening days of the slaughter, the United Nations had left four unarmed soldiers staying at the hotel as guests. This was a symbolic gesture. I was also able to bargain for the service of five Kigali policemen. But I knew these men were like a wall of tissue paper standing between us and a flash flood.