“Niko? I have decided to christen this little pool Le Cagot’s Soul.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. Because it is clear and pure and lucid.”

“And treacherous and dangerous?”

“You know, Niko, I begin to suspect that you are a man of prose. It is a blemish in you.”

“No one’s perfect.”

“Speak for yourself.”

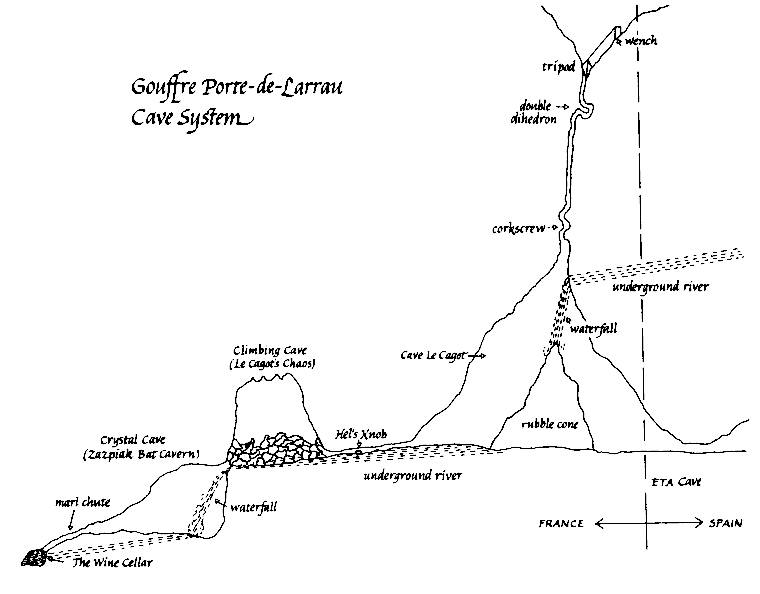

The return to the base of the rubble cone was relatively quick. Their newly discovered cave system was, after all, a clean and easy one with no long crawls through tight passages and around breakdowns, and no pits to contend with, because the underground river ran along the surface of a hard schist bed.

The Basque boys dozing up at the winch were surprised to hear their voices over the headsets of the field telephones hours before they had expected them.

“We have a surprise for you,” one lad said over the line.

“What’s that?” Le Cagot asked.

“Wait till you get up and see for yourself.”

The long haul up from the tip of the rubble cone to the first corkscrew shaft was draining for each of the men. The strain on the diaphragm and chest from banging in a parachute harness is very great, and men have been known to suffocate from it. It was such a constriction of the diaphragm that caused Christ’s death on the cross—a fact the aptness of which did not escape Le Cagot’s notice and comment.

To, shorten the torture of hanging in the straps and struggling to breathe, the lads at the low-geared winch pedaled heroically until the man below could take a purchase within the corkscrew and rest for a while, getting some oxygen back into his blood.

Hel came up last, leaving the bulk of their gear below for future explorations. After he negotiated the double dihedron with a slack cable, it was a short straight haul up to the cone point of the gouffre, and he emerged from blinding blackness… into blinding white.

While they had been below, an uncommon atmospheric inversion had seeped into the mountains, creating that most dangerous of weather phenomena: a whiteout.

For several days, Hel and his mountaineer companions had known that conditions were developing toward a whiteout because, like all Basques from Haute Soule, they were constantly if subliminally attuned to the weather patterns that could be read in the eloquent Basque sky as the dominant winds circled in their ancient and regular boxing of the compass. First Ipharra, the north wind, sweeps the sky clear of clouds and brings a cold, greenish-blue light to the Basque sky, tinting and hazing the distant mountains. Ipharra weather is brief, for soon the wind swings to the east and becomes the cool Iduzki-haizea, “the sunny wind,” which rises each morning and falls at sunset, producing the paradox of cool afternoons with warm evenings. The atmosphere is both moist and clear, making the contours of the countryside sharp, particularly when the sun is low and its oblique light picks out the textures of bush and tree; but the moisture blues and blurs details on the distant mountains, softening their outlines, smudging the border between mountain and sky. Then one morning one looks out to find that the atmosphere has become crystalline, and distant mountains have lost their blue haze, have closed in around the valley, their razor outlines acid-etched into the ardent blue of the sky. This is the time of Hego-churia, “the white southeast wind.” In autumn, Hego-churia often dominates the weather for weeks on end, bringing the Pays Basque’s grandest season. With a kind of karma justice, the glory of Hego-churia is followed by the fury of Haize-hegoa, the bone-dry south wind that roars around the flanks of the mountains, crashing shutters in the villages, ripping roof tiles off, cracking weak trees, scudding blinding swirls of dust along the ground. In true Basque fashion, paradox being the normal way of things, this dangerous south wind is warm velvet to the touch. Even while it roars down valleys and clutches at houses all through the night, the stars remain sharp and close overhead. It is a capricious wind, suddenly relenting into silences that ring like the silence after a gunshot, then returning with full fury, destroying the things that man makes, testing and shaping the things that God makes, shortening tempers and fraying nerve ends with its constant screaming around corners and reedy moaning down chimneys. Because the Haize-hegoa is capricious and dangerous, beautiful and pitiless, nerve-racking and sensual, it is often used in Basque sayings as a symbol of Woman. Finally spent, the south wind veers around to the west, bringing rain and heavy clouds that billow gray in their bellies but glisten silver around the edges. There is—as there always is in Basqueland—an old saying to cover the phenomenon: Hegoak hegala urean du, “The south wind flies with one wing in the water.” The rain of the southwest wind falls plump and vertically and is good for the land. But it veers again and brings the Haize-belza, “the black wind,” with its streaming squalls that drive rain horizontally, making umbrellas useless, indeed, comically treacherous. Then one evening, unexpectedly, the sky lightens and the surface wind falls off, although high altitude streams continue to rush cloud layers overhead, tugging them apart into wisps. As the sun sets, chimerical archipelagos of fleece are scudded southward where they pile up in gold and russet against the flanks of the high mountains.

This beauty lasts only one evening. The next morning brings the greenish light of Ipharra. The north wind has returned. The cycle begins again.

Although the winds regularly cycle around the compass, each with its distinctive personality, it is not possible to say that Basque weather is predictable; for in some years there are three or four such cycles, and in other years only one. Also, within the context of each prevailing wind there are vagaries of force and longevity. Indeed, sometimes the wind turns through a complete personality during a night, and the next morning it seems that one of the dominant phases has been skipped. Too, there are the balance times between the dominance of two winds, when neither is strong enough to dictate. At such times, the mountain Basque say, “There is no weather today.”

And when there is no weather, no motion of wind in the mountains, then sometimes comes the beautiful killer: the whiteout. Thick blankets of mist develop, dazzling white because they are lighted by the brilliant sun above the layer. Eye-stinging, impenetrable, so dense and bright that the extended hand is a faint ghost and the feet are lost in milky glare, a major whiteout produces conditions more dangerous than simple blindness; it produces vertigo and sensory inversion. A man experienced in the ways of the Basque mountains can move through the darkest night. His blindness triggers off a compensating heightening of other senses; the movement of wind on his cheek tells him that he is approaching an obstacle; small sounds of rolling pebbles give him the slant of the ground and the distance below. And the black is never complete; there is always some skyglow picked up by widely dilated eyes.

But in a whiteout, none of these compensating sensory reactions obtains. The dumb nerves of the eyes, flooded and stung with light, persist in telling the central nervous system that they can see, and the hearing and tactile systems relax, slumber. There is no wind to offer subtle indications of distance, for wind and whiteout cannot coexist. And all sound is perfidious, for it carries far and crisp through the moisture-laden air, but seems to come from all directions at once, like sound under water.

And it was into a blinding whiteout that Hel emerged from the black of the cave shaft. As be unbuckled his parachute harness, Le Cagot’s voice came from somewhere up on the rim of the gouffre.