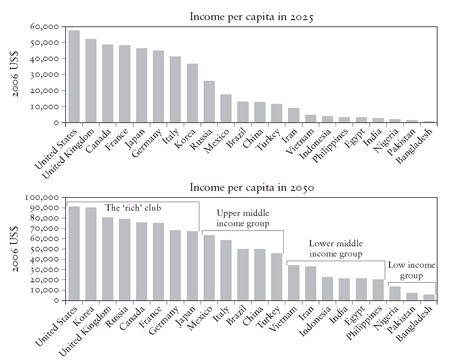

There is one other aspect of China’s emergence as a global power that is also novel. Hitherto, ever since the onset of industrialization in the late eighteenth century, the most powerful countries in the world have shared two characteristics. First, they have enjoyed one of the highest (if not the highest) GDPs of their time. Second, they have also had an extremely high GDP per head: the richest nations have also had the richest populations. That was true — in rough chronological order — of Britain, France, Germany, the United States and Japan. The only exception, arguably, was the USSR. That situation is about to change: China will share only one of these characteristics, not both. It already has a high GDP — the third highest in the world measured by market exchange rates. But even when it overtakes the United States in 2027, as predicted by Goldman Sachs, it will still have a relatively low GDP per head, and even in 2050 it will still only belong to the ‘upper middle group’ rather than the ‘rich club’ (see Figure 23). Welcome to a new kind of global power, which is, at one and the same time, both a developed — by virtue of the size of its GDP — and a developing country — by virtue of its GDP per capita.

Figure 23. Future income per capita of major countries.

The implications of a potential superpower being both a developed and a developing country are profound and multifarious. Previously the distinction between developed and developing countries was clear and unambiguous. Indeed between 1900 and 1960 there was a fundamental cleavage between those countries that industrialized in the nineteenth century and those that did not, a situation which persisted until the rise of the Asian tigers from the late fifties. This distinction between developing and developed will in future be more shaded. The continental-sized states, namely China and India, are likely to belong to both categories for many decades: their huge populations mean that they will continue to embrace very diverse levels of development and living standards within their borders. And they are in the process of being joined by other more populous developing countries such as Brazil and Indonesia, with Russia already belonging in this category.

The fact that China and India will be both developed and developing countries suggests that they will also enjoy diverse interests, namely the motives and concerns of both developed and developing countries: in effect, they will have a foot in both camps. Hitherto, trade relations have been dominated by the interests of the developed world on the one hand and the developing world on the other. Where will China and India fit in this game? Will they lean towards the developed world or the developing world, or both, depending on the issue involved? [701] It is reasonable to assume that over the next twenty years or so, both will frequently make common cause with the developing world: this can already be seen in the role of and cooperation between China, India, Brazil and South Africa in the World Trade Organization.

In the longer run, though, this will change. Assuming that both China and India continue to enjoy rapid growth for some time to come, the centre of gravity of their interests and concerns is likely to shift steadily over time from the ‘developing’ sectors of their economies to the ‘developed’, a process which will be accompanied by the growing power of those associated with the more modern parts of their economies. This is already evident in China with the increasing power of entrepreneurs and the steady decline of the farmers. A byproduct of these trends might be to embed fundamental divisions in these countries between the developed and developing parts, disparities that are a function of historic differences, reinforced and accentuated by their relationship to the inequalities and dynamics of the global economy.

China will also share another characteristic with India as a major power. China was partially colonized and India was completely colonized. The club of advanced countries — those that began their industrialization in the nineteenth century or, in the case of Britain, earlier — were those that did the colonizing. The United States, of course, also started life as a colony, but because its settler population consisted of migrants from Europe, especially Britain, its relationship to Britain as an imperial power was very different to those colonies whose people were of a different race and culture. [702] The US, moreover, was also later to acquire its own colonies. China and India will be the first major powers that were previously colonized and are composed of non-white races and cultures. In other words, China and India can identify with those who have been colonized in a way that the imperialist powers obviously cannot. This has greatly assisted China in its courtship of Africa, as we shall see in Chapter 9. Here is another powerful change in the texture and symbolism of global politics represented by the rise of China and, in this case, especially India. [703]

8. The Middle Kingdom Mentality

The journey from Fudan University on the north side of Shanghai to the Shanghai Museum in the centre must have taken the best part of an hour, perhaps longer. A decade ago the roads were not only congested but also in variable states of repair. Quite frequently in the course of my city travels, I found that taxi drivers had only a rather vague idea of where my destination might be and it was not entirely unusual to be left high and dry in what one hoped was the general vicinity of it: the city was changing so quickly that road maps were out of date before they were published, giving a whole different meaning to what in London the cabbies call ‘the knowledge’. On this occasion, though, there was no such problem; being a famous landmark in the central area of Shanghai assured familiarity.

My companion on the journey to interview the founder of the magnificent Shanghai Museum was a sociology student, Gao, who was in her final year at Fudan University before leaving to pursue a doctorate at one of the top American universities. She had been asked by her professor to assist me during my month’s stay at Fudan and she had proved wonderfully supportive. She was one of the most intelligent and committed undergraduates I had ever met and was extraordinarily well read. More than that, she was very pleasant and agreeable company, full of suggestions, always prepared to meet my requests, as well as having plenty of ideas of her own. She helped to make my stay in Shanghai a real pleasure. On this occasion she was coming with me to help with any translating that might be required during the interview.

In the taxi we talked about the interview, the Museum, which I had visited on a couple of previous occasions, and the interviews planned before my return home to Hong Kong in just over a week’s time. Then our conversation drifted on to other subjects. Gao was naturally excited about the prospect of studying in the United States and suddenly said: ‘Did you know that some Chinese students that go to America marry Americans?’ I told her about the television programme I had made the previous year about the overseas Chinese, including an interview with such a mixed-race couple living in San Francisco. ‘Actually, three weeks ago I saw a mixed couple at the supermarket checkout at the end of our road,’ I said. ‘A Chinese woman and an American guy.’ Then I added after a pause: ‘He was black.’ Why did I say that to her? I guess there were several reasons. In Hong Kong such a couple was a rare sight — indeed it was the only time I had ever seen one, and it had stuck in my mind. And my wife was Indian-Malaysian, possessed of the most beautiful dark brown skin, but I was painfully aware that not everyone perceived her colour in the way that I did, especially the Hong Kong Chinese.