Chinese democracy will share certain universal characteristics with democracies elsewhere, but will also of necessity be highly distinctive, expressive of its roots in Chinese society and traditions. Given the cultural context of Confucianism and Communism, together with the extraordinary demands of governing a continent, the invention and evolution of Chinese democracy will require enormous novelty and ingenuity. [665] There is no reason to believe, in a country which is home to the world’s oldest and most sophisticated statecraft, that this will prove impossible. But there seems little reason to believe that this process is in any way imminent. Nor will innovation in governance be a matter of one-way traffic. Just as China can learn from the American federal system and the European Union (in which it is presently showing growing interest) in governing such a vast country, so China, accounting for one-fifth of the world’s population, can also offer the rest of the world a model for large-scale governance, which is likely to become increasingly important in a globalized world.

COMMUNIST RULE

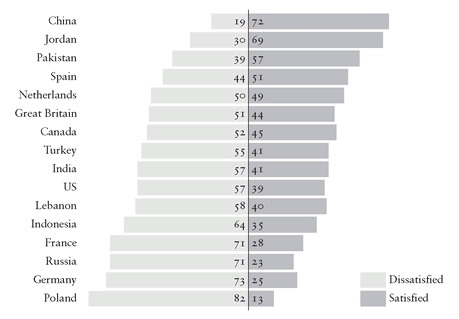

The coincidence of the collapse of Soviet Communism with the suppression in Tiananmen Square persuaded most Western observers that the Chinese Communist Party would meet a similar fate. They could not have been more wrong. In contrast to Soviet Communism, which suffered from a growing state of paralysis and ossification, the Chinese party, under Deng Xiaoping, displayed great creativity and flexibility, responding to the crisis it inherited from Mao by initiating a process of reform that has transformed the living standards of the great majority of the people. The rule of the Communist Party is no longer in doubt: it enjoys the prestige that one would expect given the transformation that it has presided over. The feel-good factor, and a concomitant mood of confidence that has been engendered, is clear from Figure 22. The uncertainties of 1989 are now a distant memory. The nature of the Party’s support and legitimacy has changed in the process: this is no longer primarily a function of ideology but depends increasingly on its ability to deliver economic growth. In that sense, China has come to resemble other East Asian developmental states, though in all these cases, as discussed in Chapter 5, the nature of governmental authority is also deeply embedded in the culture. Even though support for the Communist Party is now more contingent, there is little cause to believe that it is fragile or vulnerable. On the contrary, it is reasonable to presume that its rule is rather more secure than it has been at any time since the death of Mao, which is not surprising given its success as a governing party, and is reflected in the fact that over the last decade 20 million people have applied to join annually, even though only 2 million have been admitted each year. There is pressure for more radical political reform, as illustrated by the Charter 08 manifesto, but it remains relatively isolated and heavily policed by the state.

If the reform process has been characterized by the boldness of its economic measures, it has also been distinguished by the relative conservatism of the political changes. This is not to underestimate them. There has been the gradual spread of competitive elections to the great majority of villages and to some towns, for example in Guangdong and Fujian, where mayoral elections have been held. [666] There has been reform of the civil service, the decentralization of power to local government, and a limited rejuvenation of national and local parliaments. There has been a growing trend, largely as a result of economic necessity, towards rule by law (that is, the determination of issues according to a legal code) and, to a far lesser extent, towards the rule of law (that the law applies irrespective of the view of government), [667] which, according to one Chinese expert, applies in only 10–20 per cent of instances. [668] Given that the latter would require the Party’s power to be constitutionally limited, thereby necessitating a fundamental change in its role, its significant extension remains both problematic and unlikely. There has been a formalization of procedures such that, for example, the president can now only serve for two terms. Relations between the military and civil power have been normalized. Compared with the pre-reform period, there is far greater political space for open discussion and serious critique, [669] with the internet now the most important arena for public debate, greatly exceeding what is possible in the conventional media. [670] There have also been major reforms within the Party. Leaders are now required to retire rather than being allowed to die in office. The Sixteenth Congress in 2002 saw the first orderly transfer of power, from Jiang Zemin to Hu Jintao. Contested elections for delegates to the Party congress take place in some provinces. [671] The Party has broadened its membership, most notably, following Jiang Zemin’s Three Represents reform, to include private capitalists. And the party leadership at all levels, including the top, is more professional and better educated than it was previously. [672]

Figure 22. Percentage of population dissatisfied/satisfied with the condition of their country.

China ’s political reform has occurred gradually and incrementally. Unlike the economic reforms, the intention has never been to effect a systemic change, and certainly not to introduce Western-style democracy — rejected as incompatible with both China ’s traditions and present needs in the White Paper on Democracy published in 2005 [673] — but rather to modernize and codify political and administrative processes, thereby seeking to promote efficiency while maintaining political stability. The purpose of village elections, for example, has been good governance and functional efficiency rather than any move towards a wider process of democratization. [674] On the other hand, there has been a major expansion in civil liberties and human rights. Hong Kong opinion, which has traditionally been very sensitive to the lack of such rights in China, has become increasingly positive about trends to the north. In a 2008 survey in Hong Kong on the anniversary of the crack-down in Tiananmen Square, 85 per cent of respondents believed that human rights in China had improved since 1989, up from 78 per cent a year earlier. And the proportion who thought that they would improve further in the following three years rose to 77 per cent from 67 per cent a year earlier. Only 2 per cent thought that China ’s human rights record had worsened since 1989. [675] The boundaries of what it is now possible to say and do in China have expanded greatly, unless they concern the most sensitive subjects like Taiwan, Tibet, the Falun Gong religious sect, or the role of the Communist Party. This is most clearly apparent on the internet, which, although heavily policed in a manner that contradicts the utopian idea of the internet as a censorship-free zone, still allows a wide-ranging and frank discussion on all but the most delicate topics. [676]

[665] For an interesting discussion of some of these issues, see Bell, China ’s New Confucianism, pp. 14–18.

[666] Zheng Yongnian, Will China Become Democratic?, p. 140; and interview with Yu Zengke, Beijing, 22 May 2006.

[667] Zheng Yongnian, Will China Become Democratic?, pp. 48–70; Wang Zhengxu, ‘Understanding Democratic Thinking in China ’, seminar paper, East Asia Institute, National University of Singapore, 28 April 2006.

[669] Jude Howell, ed., Governance in China (Oxford: Roman and Littlefield, 2004), pp. 3, 8, 9.

[670] In 2006 China had 132 million internet users, the second largest number after the US.See Christopher R. Hughes and Gudrun Wacker, eds, China and the Internet: Politics of the Digital Leapforward (London: Routledge, 2003), Chapter 3; and Wang Xiaodong, ‘Chinese Nationalism under the Shadow of Globalisation’, lecture at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 7 February 2005.