It is important, in this context, to distinguish between a land-based expansion like China ’s and a maritime-based expansion such as those of the European empires of Britain and France. The European colonies never acquired any degree of permanence because, except in those cases where there was overwhelming white settlement, as for example in Australia and North America, it was impossible to assimilate races and cultures which, by virtue of place and distance, were entirely alien. This was quite different from China, which, because of its land-based expansion, always enjoyed the advantage of proximity, thereby enabling, if need be, the process of absorption and incorporation to take thousands of years. [736] As a consequence, in terms of the consciousness of its multitudinous component groups, the Chinese empire is no longer an empire, except at its northern and especially north-western and western edges, with the population of these areas representing only 6 per cent of China ’s total. [737] China thus only confronts difference, for the most part, at its perimeter. On the other hand, in terms of land these regions are extremely important, accounting for around 64 per cent of China ’s land mass. Territorially speaking, China remains an empire.

FROM UNIVERSE TO NATION-STATE

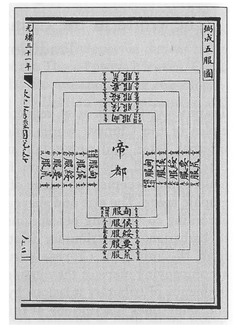

Until its engagement with Europe in the nineteenth century, China saw itself in terms quite different from those of a nation-state. China believed that it was the centre of the world, the Middle Kingdom, the ‘land under Heaven’ ( tianxia), on an entirely different plane from other kingdoms and countries, not even requiring a name. [738] It was the chosen land not by virtue of God, as in the case of Israel or the United States, but by the sheer brilliance of its civilization. Perhaps the best way to illustrate imperial China’s mentality is by the maps of the period. These consisted of a series of concentric circles or rectangles, with Beijing at the epicentre, the core formed by the northern Chinese, then progressively moving outwards across China, from those fully accepted as Chinese, to the inner barbarians, the outer barbarians, the tributary states, and finally to those condemned to outer darkness, deemed incapable of being civilized, who lived in distant lands and continents (see illustration on p. 242). [739] Imperial China, in short, embraced an utterly Sinocentric view of its place in the global order. This was not a world with a common measure, as in a system of nation-states, but instead a bifurcated world, consisting of a single ‘civilization’ surrounded by many ‘barbarians’, the latter arranged according to their cultural proximity to civilization, as in a spectrum of deepening shadows. As the ‘land under Heaven’, imperial China was a universe in its own right, above and distinct from the rest of the world, superior in every respect, a higher form of civilization achieved by virtue of the values, morals and teachings of Confucianism and the dynastic state that embodied them. Its ideal was universalism, which was the rationale for its expansion. [740]

Unlike a nation-state, its frontiers were neither carefully drawn nor copiously policed, but were more like zones, tapering off from civilization through the various states of barbarianism. [741] It is not surprising that the centre of the world did not require a name, for the Middle Kingdom needed no further explanation or description. Its mode of expansion was a combination of conquest and cultural example, its ideological justification that of a ‘civilizing mission’. [742] The Chinese system exercised an extraordinary hegemonic influence on the entire surrounding region: on the distant island of Japan and on the Korean Peninsula, which, as we have seen, both adopted Chinese characters for their writing systems and used a form of Confucianism for their moral tenets and system of governance; on the tribal nomads of the northern steppes, most of whom, when circumstances enabled or dictated, came under the Confucian spell; on what we now know as Vietnam, which was thoroughly Confucianized while fiercely defending its independence from the Chinese over many centuries; and finally, as we have seen, on the progressive Sinicization of the diverse peoples that comprise what we know as China today. Whatever the role of force, and it was fundamental, there is no brooking the huge power, influence and prestige of Chinese thinking and practice.

The Ancient Chinese view of the world

The classic ancient Chinese account of the world, dating from the sixth century BC, was the Yugong, a chapter of the Shujing (Classic of History). This highly influential document describes five major concentric geographical zones emanating outwards from the capital: royal domains, princely domains, a pacification zone, the zone of allied barbarians, and the zone of savagery. These zones have conventionally been portrayed in rectangular form, in line with the cosmological notion of a square earth.

Traditional Western political theory has been at pains to draw a firm and categoric distinction between agrarian-based dynastic regimes and nation-states. China, which has adopted many of the key characteristics of a nation-state while remaining essentially a civilization-state, confounds these kinds of traditional distinctions, as the lines of continuity between the Celestial Kingdom and modern China as a civilization-cum-nation-state indicate. [743] Thus imperial China already enjoyed, in elemental form, some of what we understand, in a broader comparative context, to be the crucial building blocks and incipient characteristics of a nation-state. In Confucianism, for example, it possessed a state ideology par excellence, by far the most advanced of its time, which imbued the outlook of the elite and also influenced the wider population. [744] The mandarin bureaucracy — schooled in the precepts of Confucianism, devoted to the idea of service and endowed with a powerful credo of administration — was the most sophisticated civil service of its time. And the country already enjoyed a shared written language: many dialects may have been spoken across China, most of which could be understood only by their own speakers, but all the spoken versions shared a common written script and this acted as a source of affinity, identity and cohesion across the population. [745] Finally, Sinocentrism — the idea of the Middle Kingdom, the view that China was the centre of the world, the belief that Chinese civilization was the most advanced in the world — provided what might be described as a primordial form of patriotism. [746] This was not the kind of patriotism that we associate with the nationalism of the modern nation-state, but rather a belief in their own universalism, the relevance and applicability of their culture to all peoples and societies, and its inherent superiority in relation to others. Implicit in this feeling of pre-eminence, as we shall see, was an inchoate notion of racial, as well as cultural, superiority, such that the two became intimately entwined.

[736] David S. Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations (London: Little, Brown, 1998), p. 425.

[741] R. Bin Wong, China Transformed: Historical Change and the Limits of European Experience (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2000), p. 103; Peter C. Perdue, ‘Why Do Empires Expand?’, workshop on ‘Asian Expansions: The Historical Processes of Polity Expansion in Asia’, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, 12–13 May 2006; and Callahan, Contingent States, p. 87.

[744] Wang Gungwu, China and the Chinese Overseas (Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1991), pp. 259-61.