Closing scene

With his holdall slung over his back, Hao An walks over barren hills, through thin forests of scraggly trees, across a bleak and desolate snow-capped land. As he nears Knotted Peach Tree Village on Fragrant Chives Mountain he can hear sheep bleating and sees a scattering of low huts in the distance. 'Maybe I've found it,' he thinks, 'maybe this is her home.' Zhang Guilan, the Li Li of his heart.

END

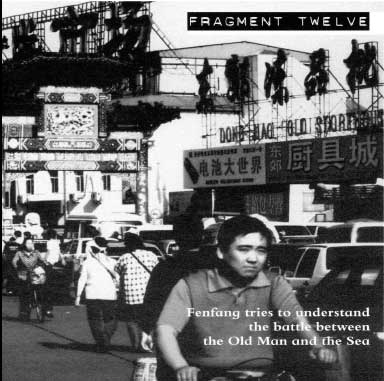

Fragment Twelve

ONCE YOU'VE SEEN A SHARK, you always take care when you walk into the sea. I was terrified Xiaolin would come round to my flat again, and that next time it might be my leg he broke, not just the light. Ever since the day I told him I was thinking of moving out, Xiaolin had been involved in a systematic process of destruction. First it was my work. He tore up scripts of films I was meant to appear in, and burnt my address book of contacts. Next were my tools. The contents of my pencil tin were repeatedly obliterated. Pencils. Rulers. Erasers crumbled. He crushed even the smallest things. I would come home to find mangled paper clips and staples strewn around the floor.

Not much escaped the shredding. Especially my photos. I loved taking pictures of Beijing. The rusty iron railings by the gates of the Forbidden City on a summer afternoon. A People's Liberation Army soldier, hunched over and shovelling snow in the winter. Beijing Canal clogged with so much rubbish it made me sad. Mao's portrait in Tiananmen Square framed by a sea of red fluttering flags. Old people playing ping pong, with their dogs fighting nearby… Each of these pictures was ripped to pieces by Xiaolin. I became a peasant again – living in a big city without any record of the past.

The teacher at my Modern American Literature evening class used to go on about Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea. He said it was one of the most important books in the history of Western literature, and we should all read it. He would hold the book above his head and talk about the battle between the Sea and the Old Man, and how it symbolised that a man can be 'destroyed but not defeated'. Somehow, whenever I thought about Xiaolin, I thought about that book. In the battle between us, Xiaolin simply refused to be defeated.

I remember a conversation Ben and I had during the one trip we made out of Beijing. We'd only been together a few weeks when Ben told me he wanted to visit this city he was studying for his PhD. Did I want to come?

It was the first time I'd been in a plane. Thin wispy clouds drifted past the window. As I watched them, I wondered whether there really was only one universe, or if in fact there were multiverses. Would life have different dimensions in another universe? Perhaps being young wouldn't mean much there, or being in love… Ben put his arm round my shoulder and pulled me back to this universe. I realised I was truly away from Beijing. Xiaolin couldn't reach me here, not unless he'd learnt to fly. I was free of the constant sense of danger. The fear that he was going to leap out at me from behind some corner.

Ben must have been thinking the same because after a while he said, 'I wish that crazy boyfriend of yours would leave us alone.'

I was quiet. Then I said, 'Maybe you can help me, Ben.'

He took his arm away. 'Oh, Fenfang. You know I want to. But I don't know how much I could offer after a while.'

What did that mean?

'Maybe we should just run away,' I said, with hope. 'Why not? China is big. We could hide ourselves in any corner, we don't have to be in Beijing. Yes?'

Ben didn't say anything.

We travelled to Changchun, a city in the north-east, in old Manchuria. When we finally unbuckled our seat-belts and got off the plane, we entered a world of ice. It was a city of heavy industry, and it seemed like it hadn't changed since 1949, the year when China became communist. The snow was black on the ground from the muck pumping out of the chimneys.

I reminded myself that this place had played such an important role in history. The Japanese had forced the last Emperor to create a fake state here in the 1930s. He'd lived in this city, surrounded by his concubines. Ben insisted we visit the Last Emperor's Palace. It was now a desolate museum. When we walked in, there was only one other visitor, a foreigner burdened by a huge backpack, squinting at obscure old photos. It's only foreigners who know about China 's history, I thought. I know nothing. But still, in that half-hour in the rotten old palace, I learnt about Pu Yi. About how he'd been crowned Emperor at the age of three. How he'd married a girl the eunuchs selected for him when he was 16. How he'd been forced to flee from the Forbidden City in Beijing. How, during the Japanese occupation of Manchuria, he tried to avoid marrying a Japanese woman imposed by the occupier. How he'd been imprisoned by Stalin in Russia. How, in 1962, Chairman Mao arranged for him to marry again, to a member of the communist party. Pu Yi. A man who had lived as a prisoner, as a citizen, as the last Emperor, and yet someone without any choice. The old man Pu Yi had obviously not defeated the sea.

Ben and I walked down a street lined with shabby shops. We ate pickled cabbage and duck-blood soup served in bowls as deep as basins. People were very generous here. It felt like any city in China was better than Beijing. We watched local teenagers skating on the frozen river, each swathed in thick padded cotton jackets. We wandered along the city's perfectly straight roads. Xiaolin couldn't reach us here. If we were to die here, in this frozen icy north, he would never know.

But the shark constantly swam back to the old man. My mobile started to ring. For some reason, I felt unable to switch the phone off. I couldn't reject Xiaolin's call. As a compromise, I turned the sound off and felt the little mobile vibrate silently. I could imagine Xiaolin, alone at home in Beijing, slamming the phone down so hard the walls shook.

That night in the Banners and Flags Guesthouse, I woke in panic. My phone had lit up. Ben could hear it vibrating against the table edge. He opened his eyes, and we both stared at it as it twinkled menacingly in the dark.

'Just leave it, Fenfang. He'll get fed up.'

'You don't know him,' I said.

Ben looked at me. 'Why can't you switch it off? I don't understand you.'

He turned his body away, exhausted.

People always say it's harder to heal a wounded heart than a wounded body. Bullshit. It's exactly the opposite – a wounded body takes much longer to heal. A wounded heart is nothing but ashes of memories. But the body is everything. The body is blood and veins and cells and nerves. A wounded body is when, after leaving a man you've lived with for three years, you curl up on your side of the bed as if there's still somebody beside you. That is a wounded body: a body that feels connected to someone who is no longer there.