'I'm in Xi'an.'

' Xi'an?'

' Xi'an, you know. The ancient city of warriors made from cooked earth. I'm just having barbecue fish.'

'What? Cooked warriors and barbecued fish?'

I listened to Ben's slow voice on the other side of the Pacific. It sounded as if he were on tiptoes in front of a large map of China trying to locate me.

'Yes, I'm in Xi'an, Ben, and everything's fine. Do you want to hear the wind?'

I lifted my phone to the night sky, high up to the wind and the dust.

Soothed by the familiarity of Ben's voice, I stood up from the fish-stall bench and called a taxi. The driver was the same maniac as before and he soon deposited me outside the Just Like Home.

Back in Room 402 I climbed into the unpredictable bed and lay there listening to the sound of the woman weeping. It was like a tide coming ever closer. Suddenly I felt terribly alone. I longed to be back in Beijing. The city that had become my home. The city where I had fallen in love for the first time. The city where rice and noodles awaited me in a kitchen cupboard. I thought about Xiaolin. Beijing was where Xiaolin and I had bought orange curtains together. A 1.8 x 2-metre red bedspread for a double bed. Where we'd held hands in the cinemas in Xiaoxitan. Where we'd eaten barbecued squid from street stalls. The city where we'd argued on street corners and eventually tried to forget each other.

I thought about the days when Xiaolin and I had lived together. His tiny apartment with the two old brown cats and the white dog that was always shitting beside our bed. And I thought about his immortal old grandmother and the bottle of Eight Dragons Soy Sauce that sat on the kitchen table, 24 hours a day, four seasons a year. Thinking of that flat made me feel like crying.

I recalled what Huizi said to me: 'Fenfang, never look back to the past, never regret, even if there is emptiness ahead.' But I couldn't help it. Sometimes I would rather look back if it meant that I could feel something in my heart, even something sad. Sadness was better than emptiness.

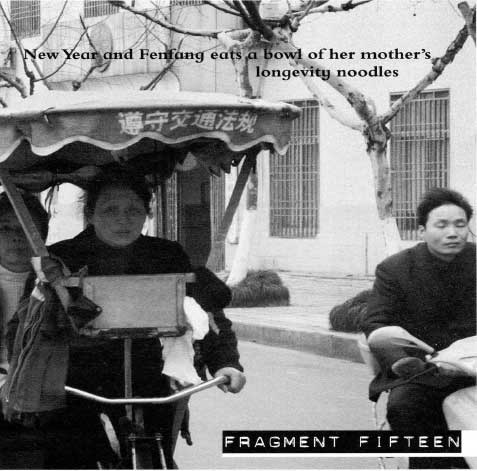

Fragment Fifteen

THE IDEA HAD BEEN GROWING quietly inside me for some time, the idea of returning. Back to the place I had run from at 17. I'd heard the village had been transformed – like so many other quiet corners of China. Hillsides had been flattened, supermarkets had been built, roads had been laid through the sweet-potato fields. The forgotten village of my childhood had become a bustling town. Even the name had changed. It wasn't Ginger Hill Village any more, it had been renamed Great Ginger Township. My father had retired from his travelling salesman job, and my mother didn't work in the fields any more, but was running a shop instead.

It was a bitter winter day and Beijing was being battered by a violent dust storm when I wrote to my parents:

Father, Mother,

I'm coming to visit. I think New Year's Day is on February 5th. So I will probably arrive on the 4th.

Your daughter Fenfang

I wrote my telephone number at the bottom and posted the letter.

Five days later I got a call from my father – the father who was absent from my childhood. His voice was hoarse and croaky, as though he hadn't spoken since I last saw him.

'Fenfang, this is your father. We'll have the New Year's Eve meal ready for you when you arrive.'

After that call, I went straight to the train station to buy my ticket.

The train journey took three days and three nights. Oh, Heavenly Bastard in the Sky, I had forgotten how long that journey was. I thought about the first time I made it, and how it had seemed as if it would never end. I had said to myself at the time, I'll only return when I'm rich or famous. But look at where I'd got to now: as poor and anonymous as all the other nobodies in bastard China.

I watched the countless cities and small towns passing outside my train window, Lang Fang, Cang Zhou, Ji Nan, Xu Zhou, Wu Xi, Hang Zhou… I smelled the dry Hua Bei Plains, saw the muddy Yellow River, and my favourite Yangzi River. In my memory, the Yangzi was light green, but this time it was grey. Construction sites full of concrete blocks lined its banks, one after another. It seemed to me that all the rivers had become much smaller and narrower. Perhaps the next time I returned home, they would have dried up altogether like the Gobi Desert.

Throughout the journey, I could see fireworks in the sky and hear the constant bang of firecrackers. I suddenly realised how long I'd spent in Beijing – cold, serious, restricted Beijing. I had forgotten how joyous New Year celebrations were. Was I really going home? I felt as if I were travelling through a dream.

As I was dragging my suitcase off the train, I saw an old woman with a decayed body and awful clothes. It was my mother.

I felt a knot in my throat. Before I could put my suitcase down, the tears started to come.

Mother watched me. She was surprised. She had never seen me cry before. She had no idea what was going on in my heart, and in my Beijing life. She had no idea why I suddenly wanted to visit them. Neither could she have known that I'd once moved six times in one year, that on one of these occasions I'd had all my belongings thrown out on the street for not paying my rent on time.

Mother, Mother, you know none of this.

My parents and I sat together at the round table, having our New Year meal. The TV was on in the background and the official national Spring Festival evening show was being broadcast on the state-run channel. I realised my parents had a new, 'Future'-brand TV set. It seemed much too modern and high-tech for their house. My mother explained that they'd bought it right after they'd got my letter. She said I'd need a large TV during my stay. Oh, that TV made my heart heavy.

It felt like a scene from a film, a typical Chinese family scene. I could almost feel the Director hovering in the background, overseeing the set-up. Father, mother, daughter, sitting together on New Year's Eve, eating and watching a famous actress singing communist songs on their newly bought TV. I couldn't care less about the show. I watched my father instead. He no longer looked like a travelling salesman. He looked old. It had never occurred to me that my father would get old. But here he was, shrinking, like all the other dried-up old people in the village. He had become even smaller than me. It clutched at my heart. I lowered my head and just kept eating the food my mother put in front of me. I lifted piece after piece into my mouth. I stared down at the bowl and worried that tears might fall into it.

My parents said nothing. They were as silent as they always had been. Only the food kept coming: endless clams. People here believed eating clams brought good fortune. If women ate them, they became fertile. On the table there was every type of clam you could fish from the East China Sea: Razor Clams, Turtle Clams, Hairy Clams. Heavenly Bastard in the Sky, I would become so fertile I could give birth to 10 children, and I didn't even know if I wanted one.

My mother broke the silence.

'Fenfang, have some more Turtle Clams. They're good for your blood. Do you still sometimes faint when you stand up?'

I looked up at her, my mouth full of fresh clam meat.

'Don't worry, Mother, that's over. In Beijing, I eat loads of strong meat. Lamb, beef, even donkey. And I eat loads of garlic too. I'm much stronger than I was before.'

'Oh?' She looked at me. 'If you're so strong, why is your face so yellow?'

I couldn't answer. Why was my face so yellow? Because I breathed in too much of Beijing 's polluted air? Because I couldn't sleep at night? Or just because I had bad Chi in my stomach? What should I say?