The strategy was installed and tested on the spot by having the woman utilize it to make an important decision that she had been putting off for weeks.

5.311 OUTCOME SEQUITUR.

In many cases where a person is looping in a strategy between a number of possible alternatives, as in the instance just cited, or when a person is having motivational problems, we will design into his strategy a representation we call the "outcome sequitur." The term means that which follows the outcome — what happens after the outcome has been achieved.

For instance, rather than simply designing and installing a strategy for a student to achieve the outcome of writing a term paper, we might also include a representation of what his experience would be like after the paper is finished as part of the outcome. Similarly, instead of having an alcoholic concentrate on the outcome of stopping his drinking habit, we would have him consider what he would be doing if he weren't drinking — as part of his outcome. This type of maneuver can often automatically positively reframe the person's experience of the specific task he is trying to accomplish by putting it into perspective with a larger train of events.

Considering the implications or outcomes of a particular outcome you are attempting to secure also has important ecological value especially if you are involved in working with businesses, organizations, families or in political situations where every outcome will propagate a series of responses from others involved in the system. The ability or inability to achieve an outcome may be based on secondary gains or contextual conditions that are not uncovered until the outcome sequitur is explored. These ecological considerations will be covered in more detail in the next section of this book.

5.312 RULES OF THUMB IN DESIGN

The purpose of design is to maximize efficiency and ease in achieving a particular outcome. There are other considerations that, although they are not well–formedness conditions, you should keep in mind while designing strategies: 1) When possible, choose the strategy that has the fewest steps — this is the modeling elegance rule again; don't complicate the strategy if you don't need to. 2) Having a choice is, in general, better than not having a choice — this goes back to the law of requisite variety mentioned earlier; variability in behavior is essential to adaptation. This also refers to the point we made earlier that the old strategies you are redesigning may still be useful in some contexts. When working with NLP you should never have to "get rid" of anything, only contextualize maladaptive behavior and design and install effective strategies. 3) When possible, opt for positive motivation when designing strategies. This is essentially an ecological consideration. Many individuals, and some institutions and organizations, have strategies that utilize negative motivation for achieving outcomes. Some people, for instance, have motivation or decision strategies that have tests that require a certain level of stress to be reached before the person will operate to access resources. The strategy keeps looping until enough stress is built up to anchor in a resource strategy. Others use punishment systems and aversive conditioning methods as motivators. And, although these methods are sometimes quite efficient and effective in securing outcomes in the short run, ecologically, because of the physiological effects of prolonged stress, pain, anger, and other negative visceral representations, they will often end up being detrimental to the health of the person or system. Also, we have found that negative anchors have a propensity to extinguish if not reinforced. Positive anchors, on the other hand, build in their own reinforcement.

5.313 Meta–Outcomes.

The topics of negative motivation and requisite variety are only two of a number important ecological considerations that occur in strategy design. One of the most important questions to ask yourself when designing a strategy or choosing an outcome is, "Will it violate personal or organizational ecology?" Make sure that the strategy you design does not go directly against any other strategies that the client has. Sometimes there will be important reasons why an individual or organization hasn't achieved some particular outcome or developed a particular strategy.

Any given specific outcome or task is framed within the context of a higher order outcome, an organizing principle or "meta–outcome" for the system (ie., the individual or organization). A meta–outcome is one that organizes the behavior of the system in terms of general goals like the preservation and survival, growth and evolution, protection, betterment, adaptation, etc. of the system. To be ecological, any other outcome or strategy must contribute to these basic outcomes. Most naturally occurring strategies and outcomes are geared for achieving the adaptive meta–outcomes, but it will be important to test to make sure those that are artificially designed are congruent with these meta–outcomes. Gregory Bateson in Steps to an Ecology of Mind discusses some of the dangers of what can happen if outcome oriented behavior is not kept ecological. (See his article, "Conscious Purpose versus Nature" pp. 426–439)

One should take note, that, as with the case of the phobic response discussed earlier in this section, some strategies and outcomes which contributed to one of these meta–outcomes at one point in time and/or in a particular context may actually be counterproductive to the achievement of that outcome in other circumstances, and it will important to include specific context markers in your design.

Often, establishing the meta–outcome first will help you in the choice and design of specific outcomes and strategies.

5.32 Applying Artificial Design in a Group Situation.

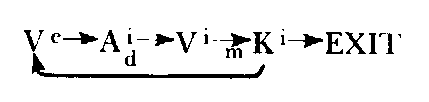

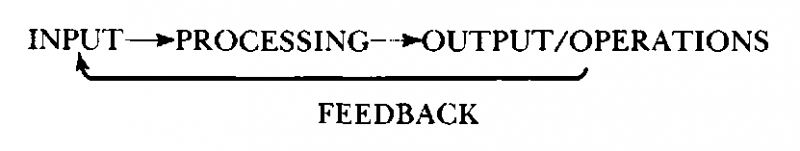

Designing a strategy for a group or organization draws from the same basic principles as individual strategy design. The purpose is to accomplish an outcome in the most effective manner possible. In an individual's strategy, the elements that you sequence to perform tests and operations are the representational systems — in an organization the elements that you sequence to perform the various tests and operations are the people. As in a strategy for an individual, a strategy for an organization will be composed of the following parts: 1) gathering and inputting information, 2) processing that information by making tests, associations, generalizations and discriminations, 3) operating and outputting in response to the outcome of this processing, and 4) gathering feedback on the effects of the operations and outputs. We can diagram these visually in the following way:

An organization is in essence a TOTE in which people are the elements that perform the test 8c operate functions instead of representational systems. In designing a strategy for an organization you will need to take the same things into account that you do when designing a strategy for an individual:

a) What is the desired outcome of the strategy? DESIRED STATE

b) How will you know if you have achieved it? FEEDBACK

c) What specific elements and functions are required to achieve the outcome? REQUIRED RESOURCES (division of labor)

d) Which of these are already available in the organization you are working with and which are missing? PRESENT STATE (Cost–benefit analysis: Should you try to obtain the missing resources, or design the strategy with what you already have?)