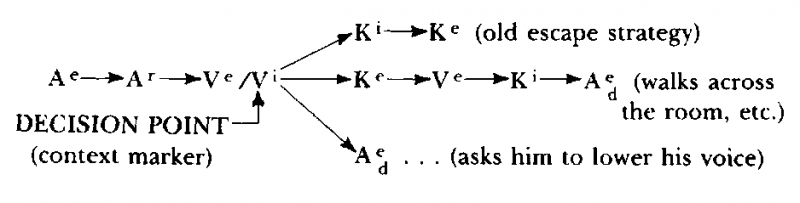

The author designed and installed a new strategy in which, as soon as she heard the volume of her partner's voice approaching that of her father, she would immediately look at him and compare the look on his face to the remembered threatening look of her father (Ve/Vr). If the two matched, then she could legitimately feel in danger and access her old response. If the two did not match (which was, of course, almost always the case) then she was to ask her partner to lower his voice (Aed) so it would be easier for her to communicate with him. If she wasn't sure, she was to walk across the room until she could look at him and feel that there was a safe distance between them (Ke→Ve→Ki), and ask him to lower his voice (Aed). A certain pairing between tonality and facial expression, then, was used as a context marker or decision criterion to choose which operation or strategy to access. Another way to think about this is that certain combinations of tonality and facial expression are programmed as anchors for different responses. We can show the newly designed strategy as follows:

5.3 Artificial Design.

The purpose of artificial design is to create a strategy that will secure the designated outcome or outcomes in the most efficient and effective manner when there is no appropriate strategy immediately available. This requires that the strategy contain all of the necessary tests and operations needed to sequence the behavior and gather the information and feedback involved in obtaining the desired outcome.

One useful method of designing effective strategies is to find a person, group or organization (depending on which you are dealing with) that already has the ability to achieve the outcome you desire to attain, and to use their strategy as a model for your design task. If you want to be able to do well in physics, find someone who already has that ability and use his strategy as a model from which to design your own. If you want to be able to get outcomes in the fields of therapy, management or law, find the people who are already able to do this and use their strategies as a model.[24] This way you will be assured that the strategy you are designing will be effective.

This method of design has many implications for the field of education. We have pointed out before that many teachers don't actually have a good strategy for the subject they are teaching. A creative writing teacher, for instance, may have a good strategy for reading and criticizing literature, but not for generating it. By finding the the strategies of a number of people who are good creative writers, the teacher could improve the quality of his course, beginning each term by teaching and installing, during the first few days of the class, the effective creative writing strategies. Once she has done this, the teacher would then proceed with the content of the course. This will increase the effectiveness of students' writing abilities. The same procedure will work for all subjects — if the strategy for incorporating and handling the material is taught first, the learning of the content will be more easily and effectively accomplished.

When consulting for educational institutions we have often organized a series of study groups for students set up in the following way. Students are covertly divided up on the basis of their ability to achieve outcomes in the particular subject in question, into fast, medium and slow students. Each study group is composed of two students from each division (two fast, two medium, and two slow). After we teach them about representational systems, pacing and accessing cues, the students elicit and swap strategies with one another for a number of subjects. Invariably, students who are slow in one task have a better strategy for some other task, and each of the students is able to offer a resource to the group. Because each benefits from the others a support network with mutual rapport tends to be built. The process of eliciting and swapping strategies is also fun. And this kind of grouping will keep students, especially of grammar school age, from being labeled and reinforced as "slow" or "stupid." In many of the places where we have set up such a program there have been dramatic improvements in the performances of the "slow" students within a matter of days.

One should be careful, of course, when designing strategies through modeling, that you don't get stuck or stagnated with one particular model for doing things. Challenging the old limitations and models and creating new ones is the basic means for improvement available to us as a species. The neurolinguistic programming model itself is continually changing, transforming and improving itself.

In designing strategies there will be some cases where any new sequence of representations you design will be more effective than the existing one. You may even wish to experiment by changing around various sequences for a particular strategy just to find out how the outcome will be affected.

When you are trying to tailor a specific strategy for a specific task and for a specific client it will be important, in addition to taking into account which kinds of discriminations in which representational systems are required for the task, to take into account the natural abilities of the client to access, gather information, and make discriminations in the various represntational systems. The design of your strategy will have to take into consideration which resources are missing and which are present in your client's existing repertoire of strategies and abilities. Some individuals, for instance, may have very limited abilities for accessing and making discriminations in one of their representational systems, and the programmer may have to first help the individual develop the representational system so that it is useful, before he can design it into a strategy. Such training may sometimes consume a considerable amount of time and energy, and the programmer may want to make a "cost–benefit" analysis as to whether it will be more beneficial to develop a particular representational system or synesthesia pattern to fit the requirements of a strategy, or to redesign the strategy to fit the existing resources of the individual.

Some people have strong and inflexible synesthesia patterns that divert or interfere with a designed strategy sequence. An individual, for example, who has a highly developed visual–to–kinesthetic synesthesia pattern may have a very difficult time performing that operation in reverse — that is, going from feelings to images. In such cases much time may have to be spent interrupting the inflexible synesthesia pattern and rehearsing and developing the new one(s).

The time spent on developing representational systems and flexibility in synesthesia patterns, however, is generally well worth the trouble. Teaching somebody to access and gather information through an underdeveloped representational system can bring about dramatic changes.

One of the authors was once working with a person who had been diagnosed and institutionalized as a paranoid schizophrenic. The author quickly noticed that the person had one essential strategy for decision making, motivation, remembering, etc. This strategy was to take any of the experiences in his other representational systems and transform them into internal kinesthetic sensations. Although this was limiting in itself, it was complicated by the fact that the person was only able to make three basic distinctions in his kinesthetic experience — "anger", a kind of neutral calmness and a kind of "fear/paranoia". All of the person's ongoing experience was interpreted and boiled down into one of these three categories, with a primary emphasis on "fear/paranoia," of course. As therapy, the person was simply taught to make more and more distinctions in his kinesthetic experience and to practice different synesthesia patterns. As his ability to discriminate feelings improved, his repertoire of behavior increased rapidly (much to the surprise of the hospital staff) because it was no longer always channeled through the previous kinesthetic bottleneck of three feelings. As the person's feelings and choices of behavior expanded so did his ability to get along with the staff, and he was eventually discharged from the hospital.

24

We have been making plans for some time to organize a project in which the twelve people who are best able to achieve outcomes in each of the major divisions of the sciences and the arts will be modeled for their strategies. This would result in a battery of the most effective strategies for many fields or sectors of organized human behavior.