No technique will magically and automatically bring about change. There are many, many conditions brought to bear on the process and results of a therapeutic interaction. It will be an absolute necessity for you to continually check your work at each step of the way. We have said before that the meaning of your communication is the response that you elicit, regardless of what you actually intend. You should never presuppose your behavior will always have the same effect. An anchor that you have established in one context may be inoperative in a different context. Constantly use your sensory awareness to test the outcomes of your communication in your client. If you find that what you are doing is not working, try something else. If you have proved to yourself that it won't work, why repeat it? There will always be another resource you can elicit, or another strategy to try. If you find that you are running into resistances, interference or incongruence, re–establish rapport and gather more information. (For other methods of dealing with interference phenomena, see the Installation Section of this book.)

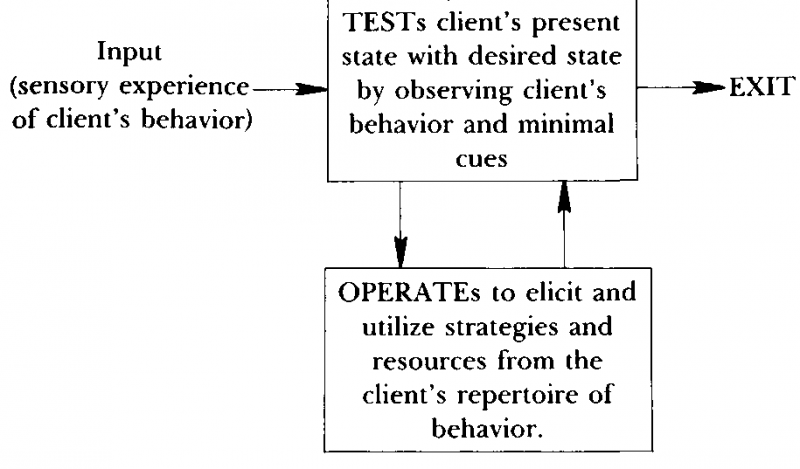

We can represent the behavior of the client and programmer, involved in a successful interaction, as two TOTEs:

This shows that the programmer is continually testing the client's present state against the desired outcome and operating to access more resources in the client until the present state and desired state are finally one and the same (that is, until the client has exhibited the desired outcome). The programmer's tests are based on sensory information gathered and stored through all of his/her representational systems.

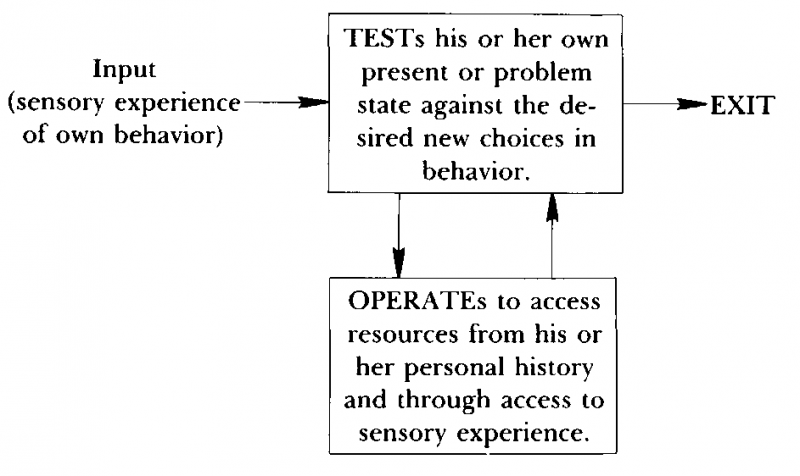

2) Client's TOTE:

The client must also have a way to test his own progress so that he may continue or initiate the process if necessary at some point when the programmer is not around. Also the client may need to access and utilize information concerning his present state and desired state (perhaps at the unconscious level), information that is not necessary for the programmer to know. All that the programmer needs to know is the result of the test. The client's representation of his present and desired states will consist of 4–tuples and strategies that compose the two states. The client operates to access personal resources until the desired outcome is reached.

One interesting phenomenon we have noticed about many therapists who have participated in our seminars is that, though they have a good TOTE for therapy and can help other people to access resources, they have difficulty accessing resources in themselves when it comes to dealing with their own problems. This is because most of the strategies they have developed for accessing and utilizing resources are triggered by their external auditory and visual experience of their clients' states (a valid strategy for working with other people). Their experience of their own problems, however, is primarily in terms of internal kinesthetic, auditory and visual representations, and fails to trigger their programs and strategies for accessing resources. We humorously refer to this as phenomenon as "therapist's syndrome." When confronted with their own internal experience therapists often have no ready resource programs with which to deal with them. This leads to other negative kinesthetic experiences like "guilt" and "frustration" because the therapist thinks if he can't even handle his own problems, how can he reasonably presume to be assisting someone else?

A good example of how NLP utilization procedures may be used therapeutically is provided by the following account of how one of the authors assisted a therapist in overcoming such a situation during one of his workshops. Outside the therapeutic context of her office when she was working with her clients, this particular therapist would have a strong phobic response to any mention of blood or gore, or in response to any threatening gesture or tonality regardless of whether the gesture was feigned or an actual threat. The response was so strong that she would actually keel over forward, holding her face in her hands. This response had been accidentally elicited a number of times by the other participants in the workshop as they went through exercises, and it was greatly interfering with her ability to participate and learn in the context of the workshop. Because of the severity of the problem the author decided to work with her in a demonstration during the workshop.

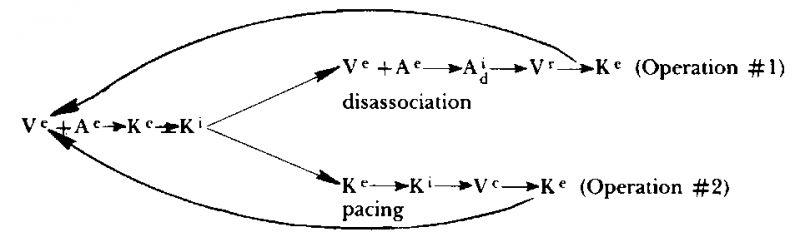

The author began by first eliciting a resource strategy — specifically, the strategy that she used to work with her clients. It was a fine strategy for therapeutic work which included two basic subroutines. When a client would come in the therapist would first carefully observe him visually and auditorily (Ve +Ae). As she observed, she would begin to pace him posturally, gesturally, and with her breathing (Ke). As she did so, she would begin to get internal feelings about the client and would have the experience of somehow stepping into the client's body (Ki). If the feelings she got from this were too negative or too intense, she would access an operation that involved a dissociation from her feelings by refocusing her attention completely on external visual and auditory experience (Vc→Ae). She would then ask herself or talk to herself about what could be done with this client (Aid) and begin to remember images of what she had done with previous clients (Vr). When the image reached a certain degree of clarity she would implement physically with the client (Ke) what she had seen. She would then test the result of her actions through her external sensory channels and repeat the process of pacing as a test to find if the intense kinesthetic feelings had begun to subside. If they hadn't she would repeat this subroutine. If the feelings had lessened enough she would begin a second operation which involved a continued pacing of the client's posture, gestures and breathing (K e) and would start to operate on the feelings she got from them (K1). These feelings would access constructed images of possible interventions she could make (Vc) which she would immediately implement (Ke). She would then return again to the beginning of the strategy and test the results of her intervention by observing the client's response through her external sensory channels. In her estimation, this operation was much more creative than the other. Represented in its entirety, we could show this strategy as:

The author noted that as the therapist discussed this strategy her posture was erect and her shoulders were thrown back. Her head was tilted slightly upward and she breathed evenly from her chest.

The strategy in operation during her phobic response was a simple but powerful Vi-→Ki synesthesia. The external triggers would access a rapid internal visual image which would immediately anchor a strong kinesthetic reaction. In this state the posture of the therapist was slumped forward, head to her knees, eyes closed and watery with her hands covering her face. The elicitation procedures uncovered that the image was one of herself as a child, where she had been consistently and severely mistreated and beaten by her parents.

The following is a transcript of how the author ("A") utilized the therapist's ("T") resource strategy to help her overcome the phobic response. The transcript begins after the author has re–elicited the phobic response so that he may work with it. He has previously established a resource anchor with the therapist (self–initiated) in which the tighter she squeezes his wrist the more she can access a particularly positive reference experience.