It is important, then, for the physician to establish rapport with patients and gather information about patients' strategies before presenting them with consequential information. It is always a good idea to elicit and anchor a resource strategy with the patient. The strategy may then be reaccessed and utilized in situations that may be difficult or important.

4.44 Law

One of the primary tasks of an attorney is representation. The attorney's ability to gather information and establish rapport with clients, witnesses and judges will determine to a large degree his professional success. If a lawyer needs to present a brief or a case to a judge for a decision, for example, it will be extremely useful to know that judge's decision making strategy. By packaging your presentation so that it paces the judge's strategy, it will be easier for him to appreciate the value of your argument. The same principle applies, of course, to juries.

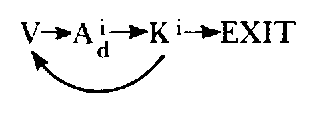

Because of their training in the use of language, we have found most lawyers and judges to be remarkably (though unconsciously) explicit in describing their internal processes through their speech. One of the authors was recently a plaintiff at a small claims trial. As the author waited for his case to be called, he listened to the judge and identified his decision making strategy. Every time the judge decided a case he would give an account of how he came to the decision, describing the form of his internal processes each time. For example, the judge might say, "Well, Mr. X, as I look over these records I see that this is not your first time in this courtroom, and I have to ask myself "How much longer will this go on? … How many more times?" I really feel that it's my responsibility to make sure that this doesn't happen again." This indicates a decision strategy of:

When it came time for the author to present his case, he packaged his presentation to pace this strategy. A skeletal paraphrasing of this presentation might go — "Your Honor, as you look over the case in front of you, you will clearly see that the defendant did not complete the work he contracted to do … And you'll have to ask yourself, 'Given the available information about the amount of work completed and the agreement made by the defendant, what is the best course of action?' … And I'm sure you will feel, as I do, that this matter should be decided in my favor."

After hearing the arguments the judge favored the author but questioned the amount of the claim presented (the author was asking for a full return of what he had paid the defendant even though the defendant had completed half of the work). The author again presented his argument in a way that paced the judge's strategy. The appeal was to the following effect: "Your Honor, I had to look at the amount of work the defendant did in perspective with the amount of time, difficulty and delay it cost me personally … and I had to ask myself, 'Is it fair to ask for compensation for all of the extra trouble I've been put through?' And I felt that the claim I was making was a reasonable compensation for all of the tension and frustration I had to go through."

The judge agreed and decided the case in the author's favor— for the full amount of the claim. Note that even though the author used himself as the referential index in this last argument — he talked about his own internal processes rather than directing the judge as he did earlier — it still served to pace the judge. The judge had to access the same sequence of representational systems to make sense of what the author was saying.

The arguments in this last example were paraphrased simply, and most of the content details were left out so that the form of what was being done would be more obvious. Most of the content involved in this kind of utilization will be provided by the situation, and, of course, should be fed back into the appropriate slots. Content considerations like picking up and pacing the appropriate legal terms and vocabulary, and relevant precedents, will also be extremely helpful, but as we have pointed out many times, the packaging is more influential than the content.

The same tactics used by the salesperson for a multi–person presentation, described earlier in this chapter, can be utilized by an attorney making a presentation to a jury. Information about the strategies of each individual jury member may be gathered through questioning during jury selection and by observing their eye movements and other accessing cues as they respond during trial proceedings. Then, by using analogue (nonverbal) markings, minimal cues and embedded commands (see Patterns I and II), direct your presentation at individual members of the jury and pace their strategies. In some cases you can be as direct as walking up to a jury member and talking directly to him.

If you want to convince them of a particular point, package your communication to match their belief strategies. If you want to influence their decision, utilize their decision making strategies. If you know their strategies well enough, you will know what conclusion they will arrive at, given the available information, so that you can predict and to some degree control what will happen when they are no longer in your presence. You will be able to predict how people of various strategies will interact with one another. And by observing accessing cues and other minimal cues (slight unconscious head shakes or nods, sighs, breathing changes, etc.) you will get feedback for how individual members are responding to your presentation and that of your opposition. You may know that person 1 responded positively to verbalization "X", and will probably be arguing in its favor; person 2 got feeling "Y" from the verbalization and will probably be leaning in a different direction and so on.

It will make your utilization a lot less complicated if you are able to select jury members who all share the same strategy — preferably your own. (Background, sex, political beliefs, and other content differences should be secondary to strategies as selection criteria.) If the opposing attorney shares your strategy, however, it may be better to select a jury of different strategies and rely on your own flexibility in pacing. It may also be to your benefit to hang a jury. In such a case you would want to select jury members of widely varying or opposing strategies. It would be possible to accomplish this by selecting part of the jury to have strategies which pace that of the prosecuting attorney, and the other part to have strategies pacing those of the defense attorney.

Covert anchoring and nonverbal communication can be extremely effective in courtroom situations. Courtrooms are a unique environment for communications because conscious attention is placed overwhelmingly on the digital (verbal) content of the communication (for instance, only the verbal portions of a trial are recorded and later considered). This leaves most of the nonverbal interchanges to take place covertly. Although a great deal of nonverbal intimidation and rapport building occurs in courtrooms, it is generally consciously ignored as significant to the final decision making process. Intimidation or rapport can be strengthened by covertly establishing negative or positive anchors. For example, one of the authors once accompanied a friend to a hearing (a jury was not involved) to observe the proceedings. During a few relaxed moments before the official proceedings had begun, the judge knocked over some objects on his desk accidentally. The court recorder made a witty remark about the judge's "heavy handedness" which immediately set the judge back at ease and even induced genuine laughter from him. The author seized the opportunity to establish a covert anchor for the positive experience by clearing his throat in a unique but innocuous manner that was loud enough to be within the audible range of the judge. A number of other cases were called before that of the author's friend, which gave the author time to reinforce the positive anchor by reproducing the unique clearing of the throat anytime the judge exhibited a noticeable positive response during the proceedings. When the author's friend's case was called the author cleared his throat a number of times as his friend was being initially questioned and inspected by the judge, and frequently during the court proceedings (although not so frequently as to seem out of the ordinary). A quick rapport was established between the judge and the author's friend which lasted throughout the proceedings, which were eventually settled in favor of the author's friend.