The Soviets were equally touchy about the Parrot’s Beak peninsula which outflanked both Jalalabad to its north and Khost to its south. The Mujahideen dumps concentrated in this area were closer to Kabul than either of these two Afghan towns. We despatched nearly 40 per cent of our supplies for the entire guerrilla war effort from this area around Parachinar. The cork intended to stem the flow was the Afghan garrison at Ali Khel, 12 kilometres from the border.

Of similar significance to Jalalabad, but south of Parrot’s Beak, was the town of Khost. Its garrison, from the Afghan 25th Division and 2nd Border Brigade, was responsible for maintaining the small border posts facing Miram Shah in Pakistan. Through Miram Shah ran another branch of our supply pipeline, carrying a good 20 per cent of the Mujahideen’s arms requirements.

Soviet border strategy was based on maintaining a multitude of posts, large and small, close to Pakistan. They were intended to seal the border and interdict our supply routes. It was rather like a person trying to shut off a large tap by putting his hand over it. Throughout the war the majority of these garrisons have been under at least partial siege, and many times small posts have fallen to attack. These eastern provinces have seen some of the fiercest fighting of the campaign, with battles resembling conventional war being fought in several instances. In fact, with hindsight, these towns and posts probably diverted our efforts too much from Kabul and other more suitable guerrilla targets. It was tempting to try to take isolated garrisons adjacent to the border. They were close to our main base with all the advantages that gave; small successes were not difficult to achieve and Commanders could be certain of recognition for their victories. Plunder and publicity were the rewards of some comparatively easy, low-risk triumphs.

In strictly military terms an isolated fort is only beneficial if it ties down more enemy in besieging it than its own garrison, or it threatens a supply line which necessitates a strong enemy masking force to prevent forays. Judged by these criteria perhaps the continuous and costly efforts of the Soviets and Afghans to maintain these posts was worthwhile. There is little doubt they tied down large numbers of Mujahideen. Two examples of this were the garrisons at Ali Khel and Khost, both of which were under continuous siege from early in the war. At both these locations operations alternated, with the Mujahideen concentrating up to 5,000 active fighters, cutting off supplies to the garrisons, seizing outlying posts and threatening to capture the town, followed by a major Soviet/Afghan thrust to break the investment. These were usually successful, with the Mujahideen melting back into the mountains along the border, only to return again when the enemy columns withdrew. In 1983 it looked for a while as if Khost would fall. At the end of August, with the situation critical, the Kabul regime flew in Colonel Shahnawaz Tani’s 37th Commando Brigade by helicopter. This forced us back after bitter fighting. By October the commandos were back in Kabul and we were closing in again.

By 1985 the Mujahideen Leaders and senior Commanders were determined that Khost should fall, and a major offensive was mooted to this end. To take a strongly-held town such as Khost was not really a task for a guerrilla force. It would require the cooperation of at least two parties and their Commanders to mobilize sufficient men. Even then, the militarily desirable ratio of 3:1 in favour of the attacker could not be achieved. Couple this with the Mujahideen’s exposure to air attack and the likely massive Soviet/Afghan response that would be provoked, and the doubtful wisdom of such an assault is apparent.

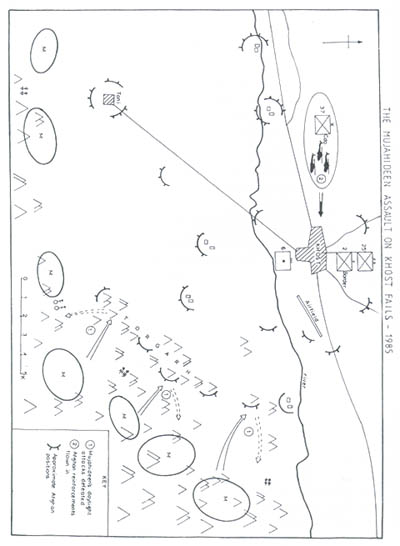

I called a conference in Peshawar to discuss the problems. It was to be a combined effort between Khalis’ and Gailani’s Parties, with Jalaluddin Haqqani, a renowned Khalis Commander, playing a leading role from his forward base at Zhawar only 6 kilometres over the border opposite Miram Shah, and some 20 kilometres south of Khost. I found that Gailani was not ready, while Khalis pressed me hard to give the go-ahead, and issue the necessary heavy weapons and ammunition. Although I had misgivings I had previously decided I would give this operation my full support provided the Commanders would mount a joint attack in accordance with a sound tactical plan. I had resolved to go into Afghanistan myself to coordinate the assault, and to send in several Pakistani teams of advisers with various Commanders. On Map 14 I have shown the tactical situation.

Khost was surrounded by mountains in which sat the Mujahideen. All around were a series of defensive posts and minefields, with a substantial garrison at Tani. The Mujahideen were particularly strong to the south and SE of the town, with their outposts overlooking the plain along the line shown on the map. The only feature that they did not occupy, as it was held by the enemy, was Torgarh. This mountain ridge was about 9 kilometres from Khost, with its northern end curling round to within 4 kilometres of the totally exposed airfield. In fact this strip was seldom used by the Afghans as we could bring it under fire so easily that they often resorted to parachute dropping of supplies. Torgarh was what the military term vital ground for any force wishing to defend or attack Khost.

I explained to the assembled Commanders that phase one of any assault on Khost must be the taking of Torgarh by night. To my dismay they all wanted a daytime attack. For hours I tried to convince them that this would be folly, with the Mujahideen exposed to heavy fire from the air and artillery long before they could reach Torgarh itself. The principal Commander, Haqqani, would not budge. My attempts to enlist the support of ax-Colonel Wardak, the military representative from Gailani’s Party, failed, as he was reluctant to oppose Haqqani for political reasons. Haqqani argued that by day everybody would do their best, nobody would hold back in front of his comrades, while in a night attack nobody would cooperate and everybody would blame each other for failure. He believed that only by day could Commanders exercise control. He assured me of success, and accepted full, personal responsibility for the operation.

At the end of a day of fruitless discussions I said to Haqqani, “I am not prepared to be a party to a plan which I know for certain will not only fail, but result in heavy casualties.” I withdrew Pakistani adviser support, but later relented and allowed two teams to go in.

The Torgarh attack was timed to start at 10.00 am (H-hour), but the inevitable delays meant that it was midday before the Mujahideen started moving forward. Regrettably, as I had forecast, the attack was broken up by concentrated fire. The Mujahideen suffered numerous unnecessary casualties. After dark some progress was made up the slopes of Torgarh, but, with the exception of taking a few bunkers, little could be achieved. By midnight they had had enough and fell back, carrying their dead and wounded with them.

After two weeks Haqqani came to me to apologize for rejecting my advice. He admitted his error, and in the same breath urged me to allocate him more weapons and ammunition. He wanted to try again—by night. But by, then the Afghan hold on Torgarh had been consolidated. I declined a second attempt. Reinforcing failure has never been a sensible military tactic.

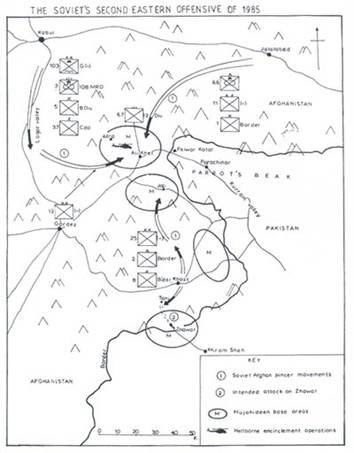

My prediction that such a large-scale attack would provoke a correspondingly strong retaliation was also proved correct. On 20 August the enemy launched their second eastern offensive of 1985, involving some 20,000 men. A series of pincer movements (shown on Map 15) were aimed at flushing out the Mujahideen from their strongholds west of the Parrot’s Beak around Azra, Ali Khel and Khost. From the latter their intention was also to move south, up to the border, and demolish the Zhawar base area. Considerable use was made of heliborne encirclement, particularly around Azra. No less than nine landing zones were used to position the cordon troops of Soviet air assault units around guerrilla bases or villages. It was a similar story around Ali Khel, with the attackers able to secure several small arms caches and inflict losses on the Mujahideen.