The situation at Zhawar was identical. The Mujahideen worked enthusiastically at tunnel-building, using bulldozers and explosives to produce seven tunnels dug into the side of a wide, dried-up nullah. They included shelter for a mosque, garage, armourers’ shop, small medical aid post, radio station, kitchen, guest house and stores. A generator provided power for the aid post, mosque and guests’ tunnel. It was even possible to watch video films at the base. This work always had priority over the tactical defences facing the enemy. The Parties and Commanders were eager to have an impressive ‘showpiece’ for visiting journalists. The fact that the previous attempt to reach Zhawar in September had petered out gave them a false sense of security.

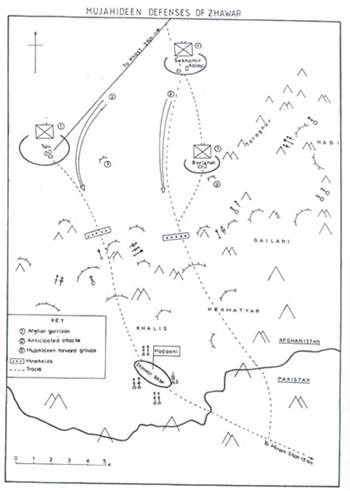

Map 16 shows the approximate defensive deployment for the battle of Zhawar, which took place in April, 1986. Zhawar was a substantial administrative base. From there operations against Khost were planned and conducted; it was a Mujahideen centre for training recruits on both small arms and heavy weapons; it was the focal point of what was regarded as a liberated area, where a sort of mini-government had been set up, courts were held and delegations and journalists were received. The principal Commander was the tall, blackbearded, 50-year-old Haqqani from Khalis’ Party, although Hekmatyar, Nabi and Gailani also had Commanders in the vicinity. Haqqani had some forty to fifty subordinates under his direction, with probably 10,000 Mujahideen spread over the border district between Ali Khel and Zhawar. I have shown the line of the forward defences at Zhawar as following the foothills of the mountains up to 10 kilometres from the frontier, although smaller outlying groups were located on the Khost plain.

The AA defences were dependent on three Oerlikon guns, the 12.7mm and 14.5mm machine guns, and shoulder-fired SA-7s, which were often sited up to 7 kilometres forward of Zhawar itself. Likely ground approaches for armour or infantry were protected by anti-tank minefields, mortars, recoilless rifles and RPGs. Some positions were connected by field telephone or walkie-talkie radios. While, in theory, the tactical handling of the defence was Haqqani’s responsibility, in practice individual Commanders would fight their own battles, with Haqqani devoting his efforts to coordinating logistic support. The weapon positions shown on the map are not completely accurate but are indicative of the layout and type used.

In Zhawar base itself, in and around the tunnels, about 400 men were deployed for its close protection, or to work on administrative support. Here also was Haqqani’s headquarters. These Mujahideen lived in or near the tunnels, while those in the forward positions lived, ate and slept at their posts. Food was often prepared centrally, operations permitting, or even cooked in Pakistan and carried forward to the Commanders. Once fighting started everybody survived on what he carried.

Although the Soviets masterminded the attack on Zhawar, they only deployed one Soviet air assault regiment from the 103rd GAAD at Darulaman, the remainder of the 12,000 men assembled for the advance being Afghans. Tactical control was to be exercised by the staff of Major-General Shahnawaz Tani, who four years later, as Defence Minister, was to launch a coup attempt against the Kabul regime, and then flee to join the Mujahideen. The Afghan Army commander on the spot was Tani’s deputy, a talented officer of Baluchi origins, Brigadier Abdol Gafur.

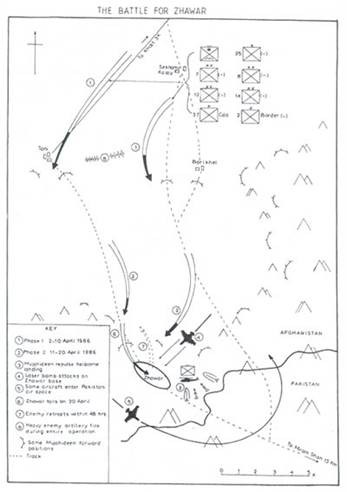

The Soviet/Afghan objective was to smash the guerrilla base infrastructure around Zhawar, occupy the area and seal off this important Mujahideen supply route (see Map 17). It was an ambitious undertaking. The operation was certain to involve tough fighting, with the Mujahideen able to call in reinforcements quickly from Pakistan. There was no way that the Khost garrison of the 25th Division and 2nd Border Brigade could undertake a mission of this size. Khost would provide a convenient jump-off point, but the bulk of the troops would have come from elsewhere. Showing a remarkable display of staff work, Gafur used the month of March to assemble his task force. Units from the 7th and 8th Divisions in Kabul, the 12th at Gardez and 14th at Ghazni were concentrated at Khost. Three battalions (1,500 men) of the 37th Commando Brigade and the Soviet AAR (2,200 men) were flown in to spearhead the offensive into the mountains. The entire operation would have the usual air umbrella, artillery and rocket support, together with scores of transport and gunship helicopters. That the Afghan Army was able to put together such an operation was striking evidence of how it had regained much of its military competence. Such an undertaking would have been unthinkable three years earlier.

As the winter weather abated in the first week of April the advance began, under cover of air-strikes and gunfire, led by Soviet and Afghan commandos in helicopters. Immediately, the ground columns came under fire from pockets of Mujahideen south of Khost and around Tani, which slowed progress to a crawl. South of Tani the operation bogged down for several days as the leading elements of the enemy came up against stiffer resistance from the mountains north of Zhawar, and groups of Mujahideen fired hundreds of 107mm rockets into Khost airfield to disrupt helicopter sorties. The second phase from Tani to Zhawar was going to require rethinking and reorganizing, so Gafur paused until 11 April.

His final plan envisaged the bold use of heliborne commandos to seize dominating ground in a coup-de-main operation close to Zhawar base, the extensive use of airpower to smash the Mujahideen positions, and the use of ground forces to link up with the commandos, and mop up what was left.

For ten days Gafur struggled to get from Tani to Zhawar, ten days of heavy fighting in which the Mujahideen resistance took a severe pounding, but during which they proved they could hold their ground even in adverse circumstances. Their outstanding triumph of this battle was the complete destruction of a battalion from 37 Commando Brigade, which was a part of Gafur’s plan to land troops behind the Mujahideen positions. In this instance they miscalculated badly in selecting as a landing zone (LZ) a flat, open plateau close to the base, but within range of higher ground held by some of Haqqani’s and Hekmatyar’s men. In broad daylight ten or more helicopters came in in waves to set down the 400 commandos. As they flew overhead they were met by a barrage of fire from SA-7s and heavy machine guns. Three helicopters crashed, while the others disgorged their troops under intense cross-fire from both Mujahideen positions. In the open ground the commandos were badly cut up and demoralized. By nightfall there was nothing left of this battalion: all were either killed or captured. Had we had the Stinger missile I doubt if any helicopter could have escaped.

From 11 to 22 April Zhawar was isolated from the rest of the area by artillery and air strikes. Pakistani air space was violated countless times as enemy aircraft wheeled overhead before diving down on their targets. Some used laser-guided bombs for pinpoint accuracy in taking out the Zhawar tunnels. A direct hit on one tunnel caused it to collapse, crushing many of its occupants, including Haqqani who was injured, but survived. Back at Rawalpindi I received frantic calls from the Parties to do something to alleviate the rain of rockets and bombs from the air. In desperation I briefed General Akhtar that I proposed asking for Pakistani volunteers from my staff to take in some more Blowpipe missiles. My logistics colonel, who had been in the anti-aircraft artillery, offered his services. He was to be accompanied by several others, including a young captain. General Akhtar agreed, so the team was rushed to the frontier. Within 24 hours they were in Zhawar.