The third way of hitting Kabul was by stand-off long-range rocket attacks. This was by far the most common method. Tens of thousands of rockets have fallen on the city and its environments during the war. Only for brief periods during the winter has a day passed without such an attack. Kabul is a huge place and so is virtually impossible to miss, but I would stress that we never deliberately fired indiscriminately. Our targets were always military, or associated with the Communist government in some way. I am not saying that innocent civilians or Mujahideen supporters were never killed by rockets: they were, but it was unintentional. Regrettably, no modern war can be fought without the innocent suffering. If we had ceased to attack Kabul because of the possibility of hitting civilians it would have pulled the carpet from under our fundamental strategy.

A revealing comment on the unintentional killing of civilians was made to Mark Urban, the author of War in Afghanistan, by Abdul Haq, a Commander who operated against Kabul. He said, “Their note 7 target is not the civilians … but if I hit them I don’t care…. If my family lived near the Soviet Embassy I would hit it. I wouldn’t care about them. If I am prepared to die, my son has to die for it, and my wife has to die for it.”

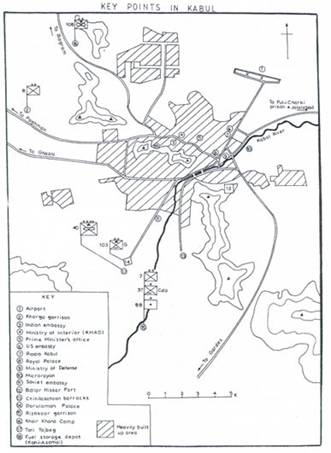

My list of potential targets suitable for rocket attack in Kabul ran to over seventy. On Map 12 I have included the important ones. The Soviet and Afghan military installations, barracks and depots were top priority. The Darulaman Palace and Tari Tajbeg Camp, which housed the headquarters of the Soviet 40th Army and Afghan Central Corps; Kabul airport, with its surrounding garrison; Chihilasatoon barracks; the camps opposite Pul-i-Charki prison; Bala Hissar Fort, with its Soviet signals regiment; Khair Khana Camp, housing a massive motor transport depot, and the 108th MRD; Rishkoor garrison, the headquarters of both the Afghan 7th Division and 37th Commando Brigade, plus the 88th Artillery Brigade; and Kargha Garrison, with its enormous ammunition depot and 8th Division headquarters, are examples of purely military targets.

First on the list of Soviet civilian establishments was their Embassy. Hardly a week went by without attempts being made to hit this building. A close second was the Microrayan district of the city. This was a sprawling, prefabricated, apartment development reserved for Soviet advisers, their families and senior Afghan Communist Party officials. KHAD headquarters buildings, all government ministries, the President’s palace, Radio Kabul (which was awkward as it was the neighbour of the US Embassy), television studios, transport pools, power stations and fuel storage tanks, all merited our attention.

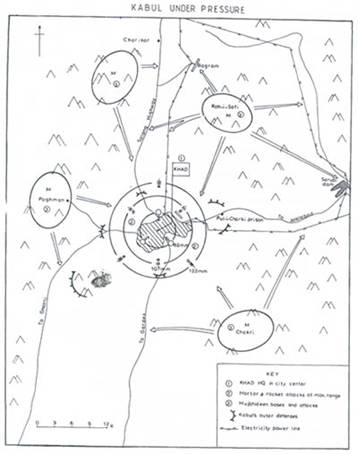

Our ability to inflict damage or casualties depended on the weapons we used and their handling by the Mujahideen. With the weapons, it was all a question of range. How far into Kabul would the bomb or rocket fall, and therefore how close to the target must the firing-point be? It was not until early 1984 that we had 107mm MBRLs with ranges of 8 to 10 kilometres. Prior to this our artillery was the 82mm mortar, so we had to get to within 3000 metres of the target which, as the ring on Map 13 illustrates, often meant a firing point inside the city. As time passed, and the Kabul defences were pushed steadily further out from the centre, these short-range attacks became impossible to mount. The arrival of the Chinese MBRL gave us the breakthrough we needed. Although it was a cumbersome and weighty weapon it had the necessary range, accuracy and firepower. With its twelve barrels we were able literally to rain rockets on a target, provided we could hump sufficient ammunition to the firing point. This enabled us to mount truly stand-off attacks throughout the remainder of the war. Some 500 of these weapons were obtained during my time at ISI, of which 75 per cent were deployed against Kabul.

It was not only the range of the weapon that was critical for successful attacks, but the suitability of the ammunition. It was useless to hit a target if it was not damaged, destroyed or casualties inflicted. Often this meant the strike had to cause a secondary explosion or fire. We had a number of disappointments. The largest petrol storage reservoir in Kabul is located in a re-entrant on the northern side of the Koh-i-Azamai feature (see Map 12). It was an obvious objective. Our first attempt was a mortar attack which scored a direct hit, but the fuel did not burn. Perhaps the tanks were not full or there were insufficient fumes to ignite. The high-explosive mortar bomb would penetrate the tank’s cover but would not start a fire. A white phosphorous (smoke) bomb could be used for its excellent incendiary effects, but it would not pierce the top of the tank.

The next try involved three Mujahideen creeping to within a hundred metres at night before firing two rockets from a RPG-2 anti-tank launcher into the reservoir and escaping in a car. Again a direct hit, but again no fire. I had long discussions with CIA technicians on this problem, but they could not come up with a direct-fire weapon to do the job. Meanwhile local defences were strengthened, making a close approach impossible. Although it remained a target for long-range stand-off attacks, it survived the war.

By April, 1985, the Soviets had established an outer ring of defences around Kabul that extended up to 10 to 12 kilometres from the centre. This caused us grave problems in mounting rocket attacks, even with the MBRLs. The difficulties were weight and range. The MBRL was too heavy to manpack over long distances, and its range of 9 kilometres meant immunity for most targets deep in the city. As there was, at that time, no prospect of a longer-range weapon, I resorted to self-help to give us a lighter launcher.

What was needed was a single-barrel rocket-launcher (SBRL) that coma De easily manhandled by one man, at night, between hostile posts.

We obtained a ‘tube’ from a partially destroyed MBRL which the Pakistan Army converted into a workable weapon—an SBRL. It was demonstrated to the CIA and I asked them to provide this weapon in large quantities. Meanwhile, I met the Chinese military attache and asked him if he could manufacture this weapon. To my surprise he said that the SBRL used to be issued to the Chinese Army, but that it was now obsolete. It would take some time to get it back into production, but it could be done. The CIA and the Chinese cooperated fully on this project. I placed orders for 500 in 1985, and by early the following year the first consignment was flown to Rawalpindi. We had received 1,000 by late 1987. This weapon greatly enhanced our ability to hit Kabul.

The problem of range was partially overcome when we obtained the Egyptian 122mm rocket launcher which could fire out to 11 kilometres. It was not the complete answer, as, although it only had a single barrel, it was long and unwieldy, making it a difficult horse– or mule-load. Like the MBRL, it was far too heavy for manpacking. Only about 100 were obtained, and I restricted their issue to those Commanders able to fire on Kabul or major airfields.

For two hours from 9.00 pm the sky over Kabul was normally the backdrop for a spectacular firework display, with dozens of rockets roaring through the darkness, Soviet flares and searchlights, and their responding rockets and artillery fire. As most of the city’s street lights had long since broken down this duel was the only illumination in an otherwise blacked-out metropolis. By eleven o’clock most Mujahideen firing points had run out of rockets so their firing died away, but not so the Soviets. Their flares and guns kept going until morning. At 5.30 am gunships and fighter bombers would scramble to carry out sweeps over suspected Mujahideen positions. It all became an accepted routine for Kabulis, Soviets and ourselves.

Note7

the Mujahideen