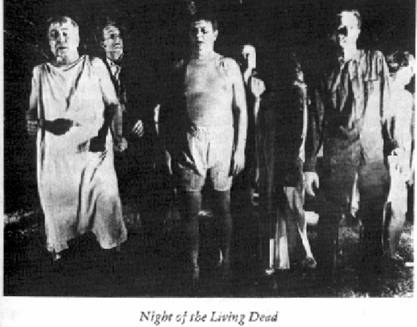

Even Night of the Living Dead has a techno-horror aspect, a fact that may be overlooked as the zombies move in on the lonely Pennsylvania farmhouse where the "good guys" are holed up. There is nothing really supernatural about all those dead folks getting up and walking; it hap pened because a space probe to Venus picked up some weird corpsereviving radiation on its way back home. One suspects that chunks of such a satellite would be eagerly sought-after artifacts in Palm Springs and Fort Lauderdale.

The barometer effect of the subtexts of techno-horror films can be seen by comparing films of this type from the fifties, sixties, and seventies. In the fifties, the terror of the Bomb and of fallout was a real and terrifying thing, and it left a scar on those children who wanted to be good just as the depression of the thirties left a scar on their elders. A newer generation-now still teenagers, with no memory of either the Cuban missile crisis or of the Kennedy assassination in Dallas, raised on the milk of détente-may find it hard to comprehend the terror of these things, but they will undoubtedly have a chance to discover it in the years of tightening belts and heightening tensions which lie ahead . . . and the movies will be there to give their vague fears concrete focusing points in the horror movies yet to come.

It may be that nothing in the world is so hard to comprehend as a terror whose time has come and gone-which may be why parents can scold their children for their fear of the boogeyman, when as children themselves they had to cope with exactly the same fears (and the same sympathetic but uncomprehending parents). That may be why one generation's nightmare becomes the next generation's sociology, and even those who have walked through the fire have trouble remembering exactly what those burning coals felt like.

I can remember, for instance, that in 1968, when I was twenty-one, the issue of long hair was an extremely nasty, extremely explosive one. That seems as hard to believe now as the idea of people killing each other over whether the sun went around the earth or the earth went around the sun, but that happened, too.

I was thrown out of a bar called the Stardust in Brewer, Maine, by a construction worker back in that happy year of 1968. The guy had muscles on his muscles and told me I could come back and finish my beer "after you get a haircut, you faggot fairy." There were the standard catcalls thrown from passing cars (usually old cars with fins and cancer of the rocker panels) : Are you a boy or are you a girl? Do you give head, honey? When was the last time you had a bath? And so on, as Father Kurt so rightly says.

I can remember such things in an intellectual, even analytical way, as I can remember having a dressing that had actually grown into the tissue yanked from the site of a cyst-removal operation that occurred when I was twelve. I screamed from the pain and then fainted dead away. I can remember the pulling sensation as the gauze tore free of the new, healthy tissue (the dressing removal was performed by a nurse's aide who apparently had no idea what she was doing), I can remember the scream, and I can remember the faint. What I can't remember is the pain itself. It's the same with the hair thing, and in a larger sense, all the other pains associated with coming of age in the decade of napalm and the Nehru jacket. I've purposely avoided writing a novel with a 1960s' time setting because all of that seems, like the pulling of that surgical dressing, very distant to me now-almost as if it had happened to another person. But those things did happen; the hate, paranoia, and fear on both sides were all too real. If we doubt it, we only need re-view that quintessential sixties counterculture horror film, Easy Rider , where Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper end up being blown away by a couple of rednecks in a pickup truck as Roger McGuinn sings Bob Dylan's "It's All Right, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding) " on the soundtrack.

Similarly, it is difficult to remember in any gut way the fears that came with those boom years of atomic technology twenty-five years ago. The technology itself was strictly Apollonian; as Apollonian as nice-guy Larry Talbot, who "said his prayers at night." The atom was not split by a gibbering Colin Clive or Boris Karloff in some Eastern European Mad Lab; it was not done by alchemy and moonlight in the center of a rune-struck circle; it was done by a lot of little guys at Oak Ridge and White Sands who wore tweed jackets and smoked Luckies, guys who worried about dandruff and psoriasis and whether or not they could afford a new car and how to get rid of the goddam crabgrass on the lawn. Splitting the atom, producing fission, opening that door on a new world that the old scientist speaks of at the end of Them! -these things were accomplished on a business-as-usual basis.

People understood this and could live with it (fifties science books extolled the wonderful world the Friendly Atom would produce, a world refueled by nice safe nuclear reactors, and grammar school kids got free comic books produced by the power companies), but they suspected and feared the hairy, simian face on the other side of the coin as well: they feared that the atom might be, for a number of reasons both technological and political, essentially uncontrollable. These feelings of deep unease came out in movies such as The Beginning of the End, Them!, Tarantula, The Incredible Shrinking Man (where radiation combined with a pesticide causes a very personal horror for one man, Scott Carey), The H-Men , and Four-D Man . The entire cycle reaches its supreme pinnacle of absurdity in Night of the Lepus , where the world is menaced by sixty-foot bunnies.*

The concerns of the techno-horror films of the sixties and seventies change with the concerns of the people who lived through those times; the big bug movies give way to pictures such as The Forbin Project (The Software that Conquered the World) and 2001, which both offer us the possibility of the computer as God, or the even nastier idea (ludicrously executed, I'll readily admit) of the computer as satyr, which is laboriously produced in Demon Seed and Saturn 3 . In the sixties, horror proceeds from a vision of technology as an octopus-perhaps sentientburying us alive in red tape and information-retrieval systems which are terrible when they work (The Forbin Project ) and even more terrible when they don't: In The Andromeda Strain , for instance, a small scrap of paper gets caught in the striker of a teletype machine, keeps the bell from ringing, and thereby (in a fashion Rube Goldberg certainly would have approved of ) nearly causes the end of the world.

*And a host of others, many of them Japanese imports, all linked by either long-term radiation or nuclear blast as first cause: Godzilla, Gorgo, Rodan, Mothra, and Ghidrah, the Three-Headed Monster . The idea was even played for laughs once before Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove, in an odd little fifties picture called The Atomic Kid, starring Mickey Rooney.

Finally there are the seventies, culminating in Frankenheimer's notvery-good but certainly well-meant film Prophecy , which is so strikingly similar to those fifties big bug movies (only the first cause has changed), and The China Syndrome , a horror movie which synthesizes all three of these major technological fears: fears of radiation, fears for the ecology, fears of the machinery gone out of control, run wild.

Before leaving this all too brief look at pictures which depend on some mass unease over matters technological to provide the equivalent of The Hook (pictures which appeal to the Luddite hiding inside all of us), we should mention some of the films dealing with space travel which fall into this category . . . but we'll exclude such xenophobic pictures as Earth vs. the Flying Saucers and The Mysterians from our view. Pictures which focus on the possible Dionysian side of space exploration (such as The Andromeda Strain and Night of the Living Dead , where satellites bring back dangerous but nonsentient organisms from the void) ought to be differentiated from those purely xenophobic movies dealing with invasion from outer space-films where the human race is viewed in an essentially passive role, attacked by the equivalent of muggers from the stars. In pictures of this type, technology is often seen as the savior (as it is in Earth vs. the Flying Saucers , where Hugh Marlowe uses his sonic gun to interrupt the saucers' electromagnetic drive, or in The Thing , where Tobey and his men use electricity to barbecue the interstellar vegetable)-Apollonian science vanquishing the Dionysian bad guys from Planet X.

Although both The Andromeda Strain and Night of the Living Dead present space travel itself as an active danger, perhaps the best example of that idea combined with the brilliant mind dangerously hypnotized by the siren song of technology comes in The Creeping Unknown , a film that predates both of the former. In that film, the first of the critically acclaimed Quatermass series, the viewer is originally presented with one of the creepiest locked-room mysteries ever posited: three scientist-astronauts are sent into space, but only one returns . . . and he is catatonic. Telemetry and the presence of all three spacesuits seem to prove that the two missing spacemen never left the ship. So where did they go?

What happened, apparently, is that they picked up an interstellar hitchhiker, a plot device we see again in It.! The Terror from Beyond Space and, of course, in Alien . This hitchhiker has consumed the survivor's two mates, leaving only a mass of sludgy gray stuff behind . . . and, of course, the hitchhiker (a kind of space spore) is now busily at work in the body of the survivor, Victor Carune, who is played with skull-like, spooky believability by Richard Wordsworth. Poor Carune ends up degenerating into a spongy, many-tentacled horror which is finally spotted clinging to a scaffolding in Westminster Abbey and dispatched (just in the nick of time; it is about to sporulate and create billions of these things) by a big jolt of electricity which sets it on fire.

All of this is fairly standard monster-movie fare. What elevates The Creeping Unknown to levels undreamed of in the philosophies of the creators of The Horror of Party Beach is Val Guest's somber, atmospheric direction, and the character of Quatermass himself, played by Brian Donlevy (other actors have since played Quatermass in other films, softening the interpretation a bit). Quatermass is a scientist who may or may not be mad, depending on your own views of technology. Certainly if he is nuts, there is enough Apollonian method in his madness to make him every bit as scary (and every bit as dangerous) as that blob of tentacle-waving goo that was once Victor Carune. "I'm a scientist, not a fortune-teller,” Quatermass grunts contemptuously at a timid doctor who asks him what he thinks might happen next; when a fellow scientist tells him that if he tries to open the hatch of the crashed rocket he will roast the space travelers inside, Quatermass storms at him: "Don't tell me what I can and can't do!” His attitude toward Carune himself is the cold-blooded attitude which a biologist might adopt toward a hamster or a Rhesus monkey. "He's coming along fine," Quatermass says of the catatonic Carune, who is sitting in something which vaguely resembles a dentist's chair and staring out at the world with eyes as black and dead as cinders coughed up from hell. "He knows we're trying to help him.” Yet in the end it is Quatermass triumphant-if only through blind luck. After the monster is destroyed, Quatermass brushes rudely by a police officer who is trying to tell him in a halting way that he prayed they would be successful. "One world at a time is enough for me," the policeman says; Quatermass ignores him.