All of which brings us to an interesting borderline that I want to point out but not step over- this is the point at which the country of the horror film touches the country of the black comedy.

Stanley Kubrick has been a resident of this borderline area for quite some time. A perfectly good case could be made for classing Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb as a political horror film without monsters (a guy needs a dime to phone Washington and stop World War III before it can get started; Keenan Wynn grudgingly obliges by blowing a Coke machine to smithereens with his burpgun so our hero can get at the change; but he tells this would-be savior of the human race that "you're going to have to answer to the Coca-Cola Company of America for this"); for A Clockwork Orange as a political horror film with human monsters (Malcolm McDowell stomping a hapless passerby to the tune of "Singin' in the Rain"); and for 2001: A Space Odyssey as a political horror film with an inhuman monster ("Please don't turn me off," the murderous computer HAL 9000 begs as the Jupiter probe's one remaining crewman pulls its memory modules one by one) that ends its cybernetic life by singing "A Bicycle Built for Two." Kubrick has consistently been the only American film director to understand that stepping over the borderline into taboo country is as often apt to cause wild laughter as it is horror, but any ten-year-old who ever laughed hysterically at a traveling-salesman joke would agree that it is so. Or it may simply be that only Kubrick has been smart enough (or brave enough) to go back to this country more than once.

6

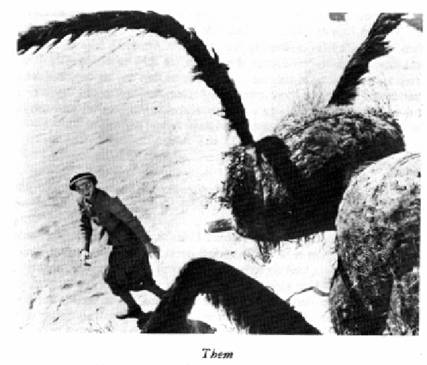

"We have opened a door on an unimaginable power," the old scientists says gloomily at the conclusion of Them! , "and there will be no closing it now.” At the end of D. F. Jones's novel Colossus (filmed as The Forbin Project ), the computer which has taken over everything tells Forbin, its creator, that people will do more than learn to accept its rule; they will come to accept it as a god. "Never!" Forbin responds in ringing tones that would do the hero of a Robert Heinlein space opera proud. But it is Jones himself who has the final word-and it's not a reassuring one. "Never?" reads the final paragraph of his cautionary tale. *

In the Richard Egan film Gog (directed by Mr. Flipper himself, Ivan Toss), the equipment of an entire space-research station seems to go mad. A solar mirror twirls erratically, pursuing the heroine with what amounts to a lethal heat ray; a centrifuge designed to test would-be astronauts for their responses to heavy g-loads speeds up until the two test subjects are literally accelerated to death; and at the conclusion, the two BEM-like robots, Gog and Magog, go totally out of control, snapping their Waldo-like pincers and making weird Geiger-counter-like sounds as they roll forward on various errands of destruction ("I can control him," the cold-fish scientist says confidently only moments before Magog crushes his neck with one of those pincers).

"We grow them big out here," the old Indian in Prophecy says complacently to Robert Foxworth and Talia Shire as a tadpole as big as a salmon jumps out of a lake in northern Maine and flops around on the shore. Indeed they do; Foxworth also sees a salmon as big as a porpoise, and by the conclusion of the film, one is grateful that whales are not fresh-water mammals.

*D. F. Jones could hardly be classed as the Pollyanna of the science fiction world; in his followup to Colossus , a newly developed birth control pill that you only have to take once results in worldwide sterility and the slow death of the human race. Cheery stuff, but Jones is not alone in his gloomy distrust of a technological world; there is J. G. Ballard, author of such grim tales as Crash, Concrete Island, and High-Rise ; not to mention Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (whom my wife fondly calls "Father Kurt"), who has given us such novels as Cat's Cradle and Player Piano .

All of the foregoing are examples of the horror film with a technological subtext… sometimes referred to as the "nature run amok" sort of horror picture (not that there's much natural about Gog and Magog, with their tractor treads and their forests of radio aerials). In all of them, it is mankind and mankind's technology which must bear the blame; "You brought it on yourselves," they all say; a fitting epitaph for the mass grave of mankind, I think, when the big balloon finally goes up and the ICBMs start to fly.

In Them! it is nuclear testing at White Sands that has produced the giant ants; the Cold War has spawned dat ole binary debbil Colossus; ditto the machines that have gone nuts in Gog ; and it's mercury in the water, a side-effect of a paper-making process, that has produced the giant tadpoles and the mutant monstrosities in the John Frankenheimer film Prophecy .

It is here, in the techno-horror film, that we really strike the mother lode. No more panning for the occasional nugget, as in the case of the economic horror film or the political horror film; pard, we could dig the gold right out of the ground with our bare hands here, if we wanted to.

Here is a corner of the old horror-film corral where even such an abysmal little wet fart of a picture as The Horror of Party Beach will yield a technological aspect upon analysis-you see, all those beach blanket boppers in their bikinis and ball-huggers are being menaced by monsters that were created when drums of radioactive waste leaked. But not to worry; although a few girls get carved up, all comes right in the end in time for one last wiener roast before school starts again.

Once more, these things happen only rarely because directors, writers, and producers want them to happen; they happen on their own. The producers of The Horror of Party Beach, for example, were two Connecticut drive-in owners who saw a chance to turn a quick buck in the low-budget horror-movie game (the reasoning seeming to be that if Nicholson and Arkoff of AIP could make X amount of dollars churning out B-pictures, then they might be able to make X2 amount of dollars by turning out Z-pictures). The fact that they created a film which foresaw a problem that would become very real ten years down the road was only an accident . . . but an accident, like Three Mile Island, that perhaps had to happen, sooner or later. I find it quite amusing that this grainy, low-budget rock 'n' roll horror picture arrived at ground zero with its Geiger counters clicking long before The China Syndrome was even a twinkle in anyone's eye.

By now it must be obvious that all of these circles intersect, that sooner or later we always arrive back at the same terminus-the terminus which gives upon the land of the mass American nightmare. These are nightmares for profit, granted, but nightmares is nightmares, and in the last analysis it is the profit motive that becomes unimportant and the nightmare itself which remains of interest.

The producers of The Horror of Party Beach never sat down, I'm sure (just as I'm sure the producers of The China Syndrome did), and said to each other: "Look-we're going to warn the people of America about the dangers of nuclear reactors, and we will sugar-coat the pill of this vital message with an entertaining story line." No, the line of discussion would have been more apt to go like this: Because our target audience is young, we'll feature young people, and because our target audience is interested in sex, we'll site it on a sun-and-surf-type beach, which allows us to show all the flesh the censors will allow. And because our target audience likes grue, we'll give them these gross monsters. It must have looked like boffo box-office stuff: a hybrid of AIP's most consistently lucrative genre pictures-the monster movie and the beach-party movie.

But because any horror film (with the possible exception of the German expressionist films of the 1930s) has got to at least pay lip service to credibility, there had to be some reason for these monsters to suddenly come out of the ocean and start doing all these antisocial things (one of the film's highlights-maybe lowlights would be better-comes when the creatures invade a slumber party and kill ten or twenty nubile young things . . . talk about party -poopers!). What the producers decided upon was nuclear waste, leaking from those dumped cannisters. I'm sure it was one of the least important points in their preproduction discussions, and for that very reason it becomes very important to our discussions here.

The reason for the monsters most likely came about in a kind of freeassociation process, the sort of test psychiatrists use to discover points of anxiety in their patients. And although The Horror of Party Beach has long since been consigned to oblivion, that image of the canisters marked with radiation symbols sinking slowly to the bottom of the ocean lingers in the memory.

What in Christ's name are we really doing with all that nuclear sludge? the mind enquires uneasily-the burnoff, the dreck, the used plutonium slugs, and the worn-out parts that are as hot as a nickelplated revolver and apt to stay that way for the next six hundred years or so?

Does anybody know what in Christ's name we're doing with those things?

Any thoughtful consideration of techno-horror films-those films whose subtexts suggest that we have been betrayed by our own machines and processes of mass production-reveals very quickly another face in that dark Tarot hand we dealt out earlier: this time it's the face of the Werewolf. In talking about the Werewolf in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde I used the terms Apollonian (to suggest reason and the power of the mind) and Dionysian (to suggest emotion, sensuality, and chaotic action). Most films which express technological fears have a similar dual nature. Grasshoppers, Beginning of the End suggests, are Apollonian creatures, going about their business of hopping, eating, spitting tobacco juice, and making little grasshoppers.

But following an infusion of nuclear wolfsbane, they grow to the size of Cadillacs, become Dionysian and disruptive, and attack Chicago. It is their very Dionysian tendencies-in this case, their sex drive-that spells the end for them. Peter Graves (as the Brave Young Scientist) rigs up a mating-call tape that is broadcast through loudspeakers from a number of boats circling on Lake Michigan, and the grasshoppers all rush to their deaths, believing themselves to be on their way to a really good fuck. A bit of a cautionary tale, you understand. I bet D. F. Jones loved it.