The ground cover was moderately dense bush and there were no locals in the patrol area. The ground we were to cover was a huge game park the size of a small country and which had had no visitors for 15 years despite the presence of rhino, elephants and leopards. So the only people who were likely to cross the river were insurgents and poachers coming for the ivory on the elephants and rhino. It was difficult in these circumstances to tell insurgents and poachers apart – but, being fond of animals, I was not inclined to take the trouble.

The routine I set up was to simply mount an ambush on the river each night, shoot anything that came across and then move during the day to a new position. Doing this safely and tactically was a more complex issue.

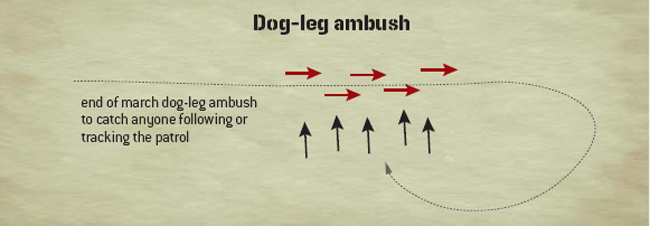

Each day we would walk down the river for 8 hours or so. Just before dark we would ‘dog-leg’ back on ourselves to ambush anyone following us and then settle down for a meal – always a mile or so from the river so as not to give away our ambush position. One man would be despatched as a scout to find a good ambush position. The scout would return after dark and lead us into the ambush position he had selected.

The reason for lying up away from the ambush position at last light was to prevent anyone following us into the ambush position and turning the tables on us.

Sundown was at 1830 and then dark followed in 5 minutes. This meant that the scout often had a difficult job to lead the team to the correct place. Sometimes it was a case of holding on to the guy in front. One night we were being led into position in this way amongst bushes when one of the bushes got up and screamed at us. It was an elephant. We turned and ran – straight into another elephant. We turned and ran again into another – we had wandered into the middle of a herd of sleeping elephants. It was so funny – afterwards.

Close by the ambush position four men would set out their light-weight sleeping bags in a cross, heads together, a few yards in from the river bank. This allowed for quiet communication amongst them. The remaining man would be on stag watching the river. Quite a nice job sat in the warm evening – watching the river flow and listening to the creatures making their noises.

A large hippo stumbled on our position one night and managed to hook one of its tusks in my mate Yves Debay’s sleeping bag. He shouted in surprise and startled the animal which let out a bellow and set off at a trot. Dragging Yves in his sleeping bag behind it. We almost laughed ourselves sick. Each environment will have its own localized dangers!

One particular night the sentry woke us to say two small boats were coming over the river. We formed up in a line on a cliff some 10ft above the water – four rifles and a machine gun – and riddled the boats from a range of some 15ft in a few seconds. Do you remember what I said about a good ambush being over in 2 seconds? Four rifles and a gun fire over 3,000 rounds per minute – that’s 54 rounds per second – and can decimate the enemy.

Then we picked up our kit and ran for a good mile. Mortar fire came over the river onto the site we had ambushed but we were well out of it. The next day we did a recce of the position but all we found was one canoe full of holes washed up on the river bank. The crocodiles had eaten well that night.

THE AMBUSH

An ambush is using the element of surprise to force a contact on the enemy at a place and time of your choosing and then, hopefully, killing him quickly while minimizing your own casualties.

We have already seen how unpleasant being ambushed can be – even when it is not done properly – so now we are going to learn how to set an ambush efficiently and make it much worse for the enemy. An ambush is particularly useful in counter-insurgency operations when the enemy generally does not want to meet you face to face. It may be the only time you get the chance to kill any of them and do so without the usual required numerical advantage.

The Author and a buddy (photographed left) sat with a radio for three weeks on this hill waiting for someone to ambush. We watched this scene every day for three weeks. And nobody came... Sometimes soldiering really is 99% boredom and 1% sheer terror. (Author’s Collection)

The simplest ambush is just waiting, hidden by a track, for the enemy to come along and shooting him when he turns up – but there are quite a number of little tricks I can show you which will make your ambushes a lot more successful and deadly. And deadly for the opposition means safer for you. As a bonus for you, the more you know about setting up ambushes the more chance you will have of spotting the ones set against you. This can only be a good thing.

Every ambush is going to be different according to the terrain, the enemy target and the forces at your disposal to set it up but we will begin by looking at the principles of the perfect ambush.

The perfect ambush

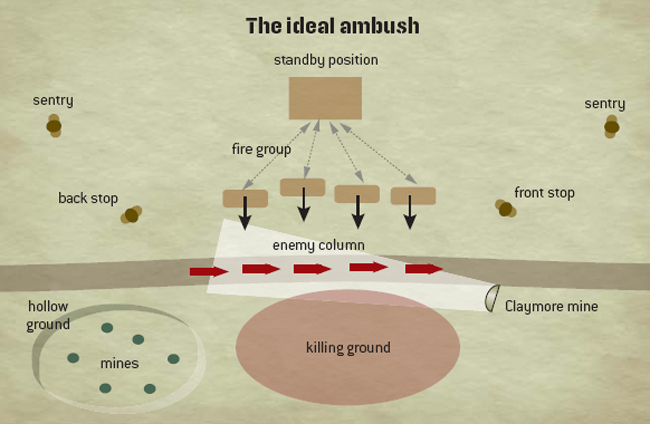

An ambush consists of a number of component parts. The diagram of a foot ambush below has them all, aside from heavy weapons, while an ambush put together on the spur of the moment may have only a few. If you know and understand the use of all the potential parts you can put together to increase your effectiveness then you can decide, rather like a good chef, when and where to use the ingredients.

In this perfect ambush there is a ‘killing ground’ behind the enemy so they cannot usefully run away, the ground rises to your position to make it difficult for them to come at you, landmines and Claymores are laid, everyone has been to their positions and can find them in the dark. The main ambush party are waiting, resting, in the Standby Position while a series of sentries watch for the approach of the quarry.

When the enemy are sighted the officer commanding confirms the intention of springing the ambush – as the enemy may be too small or large – then the main party take up their positions.

When the enemy column has moved into the ideal ambush position the commander will give the signal to spring the ambush – usually with a burst of fire. Immediately the front and rear stops fire their Claymores then rake the length of the column with small-arms fire. The main party open up at the same time with their weapons.

Should the enemy column take cover they will either be in the open and easy to hit or trigger the landmines placed in the hollow. If they break and run away from the ambush site the ground has been selected so that they cannot find cover in the open killing ground before they are killed. If the enemy choose to rush the main fire group this should be strong enough to destroy them all.

Terrain

If you are going to sit and wait in an ambush it makes sense to wait where the enemy are likely to pass. You are most likely to catch people walking along tracks or roads but where these are missing from the landscape look for river crossings, passes between mountains and similar features which might be expected to funnel the enemy in front of your sights.

Killing ground

This should be flat and open wherever possible so as to give a clear view of the enemy as they try to escape.

Fire group

The position of this should be on higher ground if possible both to give a better fire position and to make an assault difficult for the enemy.

Front stop

The task of the ‘front stop’ is to act as a cut-off to prevent the main part of the enemy escaping along their line of march. He should wait off the track in case the commander decides to let people through the ambush site. They may be civilians, or too small or too large a target. When the ambush is activated he should move into position. The front stop may also activate Claymores or other assets with an arc of fire directed back towards the enemy.