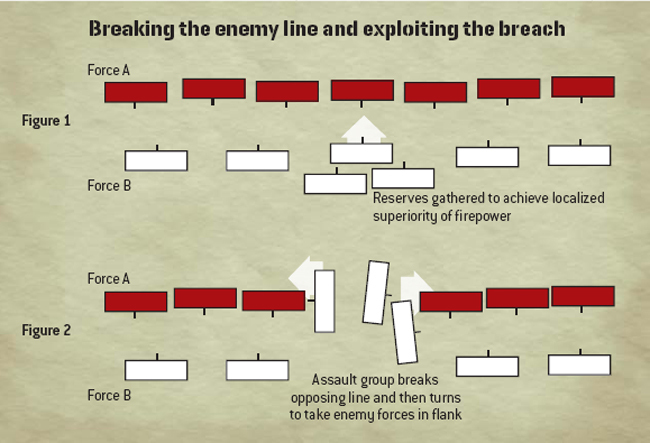

Imagine you were part of a dozen riflemen laid in a line shooting at another line of a dozen men just beyond the accurate range of your rifles – say 300–400 yards. If you each fire at your opposite number then you are all going to have about an even number of bullets cracking round your heads and be pretty much evenly matched. The odd man will get hit and each survivor will keep shooting. But if, say, eight of you all start firing at one or two men on the left of the opposite line something different happens – these guys have so much lead coming at them they put their heads down and stop shooting. If you are lucky you might even hit them. This is localized superiority of firepower. OK, in this case nothing much comes of it but the idea can be used to force a breakthrough in the enemy position as you can see below.

The word ‘localized’ is included because where two large groups are in contact – say two lines of troops facing one another – one group could thicken their line with reserves in one place to achieve a localized superiority there and use that point to break the enemy’s line. Once through the enemy line the assault group would turn left or right and ‘take the enemy in flank’. This means attack from the side where the enemy are less well defended and are confronted by a stronger assaulting force able to take them piecemeal.

As a general rule of thumb there should be three times the number of men attacking as defending to take a prepared position successfully. This is because it is generally considered much easier to defend than attack as the attackers must often cross open ground to reach the enemy and when there they must overwhelm him quickly to minimize losses. By ‘firepower’, however, I don’t just mean more rifles. If you can bring in gunships or artillery to pin down the enemy while you advance then this has, in theory, the same effect as covering fire from your own machine guns. In practice it is far better.

This is the simplest way I can describe this situation but you will understand the same thing is happening when one side is dug in and an equal-sized force is attacking them – because the defender has the advantage of firepower and cover. The same again in an ambush, the same when an artillery unit delivers a load of HE onto a position and the same when an aircraft drops its load of napalm on an artillery battery. Every situation is the same: the attacker is focusing a lot of ordnance onto a small point, the defender has no reply and is destroyed.

This is why in, say, Afghanistan, your boss flies a few dozen soldiers to attack a small group of insurgents and overwhelm them at that place with a localized superiority of firepower while there are countless thousands of insurgents elsewhere not even engaged in the fight.

Of course, the insurgent leader is trying to gather 200 of his men together without you knowing and then he will attack a little outpost of yours with a dozen of your men in it...

Does that mean soldiers are all the same?

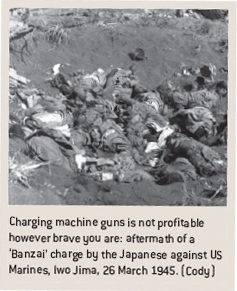

However brave, tough, fit and skilful you are personally, the outcome of almost every contact with the enemy is dependant upon who has the drop on the other and thereby achieves a localized superiority of firepower. This is what tactics is all about – getting that drop – and it is the responsibility of the officers and NCOs at their relevant level.

But to bring about a localized superiority of firepower, and even more to exploit one, requires a team of highly trained, disciplined soldiers who will move on command and work as a team. This is your contribution to the victory. That is why soldiers always win out over mobs and gangs of drug dealers etc. Because of the organization and discipline. And when two armies clash, as a rule the best trained soldiers win...

At least they do when they are lead properly. Someone once said that ‘War is a series of errors and he who makes the least errors wins’. Someone also said that ‘No battle plan survives contact with the enemy’. So when the shit hits the fan, and it will happen that you end up outnumbered 20 to one and with no support, that is when you need the tough guys with the guts and the weapons skills. And if they are tough enough they just might hold out till the cavalry arrive.

THE PATROL

What is a patrol?

The word ‘patrol’ is used to describe a force of between four men and generally less than battalion strength (750 men) given a specific operational task. This task might be to seek out and engage the enemy, to blow up a bridge, scout an area or just show the locals you are there and controlling the area. The patrol may last anything from a few minutes for a clearing patrol checking the perimeter of your camp in the morning to some weeks for a reconnaissance patrol. According to the circumstances and operational requirements patrols may be on foot, motorized or placed into area by aircraft.

All patrols are more or less aggressive acts as opposed to defensive. The idea is that you are either setting off to attack the enemy somewhere or going sneakily to do something unpleasant to him like blow up his bridge or similar. For convenience, patrols are usually described by their mission type as this is an obvious guide to their composition.

Patrols are given different names in different armies and some missions can cloud the definition of patrol so bear with me. This list will get the idea across:

The preparation for all patrols is essentially the same so we will look at this first then I will cover the differences in turn.

Necessary knowledge

The basic knowledge and soldiering skills required to perform these patrol functions will have been taught to you in basic training and supplemented by further training in your unit and other sections of this book. The actual techniques, equipment and tactics required will depend to a great extent upon the individual task and the plan of the originating officer.

A very general but useful tip is to make sure that every man in the unit understands the overall plan and aim of the patrol. Then have the men physically practice any significant or unusual actions required to complete the task – such as abseiling down a cliff, crossing a river on floats or the placing of demolition charges. A large proportion of men learn better by ‘doing’ than ‘hearing’.

Minor tactics (tactics involving infantry only as opposed to an all-arms battle group)

Spacing: It is most common to walk in a well spaced single file on patrol. This configuration has several advantages including walking in one set of tracks to reduce the chance of mine injury, lengthening the patrol to make an ambush less effective and ensuring that a mortar bomb, mine blast or whatever will catch the minimum number of men.

Too extended spacing can result in loss of contact and cohesion. The patrol might be difficult to manoeuvre in case of attack. Too close and the problems enumerated above apply. During daylight five yards is normally about right but less may be better to maintain contact in close bush or darkness.