"What do you mean I sound just like Dad?" "He used to say things like that." "Like what?" "Oh, like nothing is so-and-so. Or everything is so-and-so. Or obviously." She laughed. "He was always very definitive." "What's 'definitive'?" "It means certain. It comes from 'definite.'" "What's wrong with definitivity?" "Dad sometimes missed the forest for the trees." "What forest?" "Nothing."

"Mom?" "Yes?" "It doesn't make me feel good when you say that something I do reminds you of Dad." "Oh. I'm sorry. Do I do that a lot?" "You do it all the time." "I can see why that wouldn't feel good." "And Grandma always says that things I do remind her of Grandpa. It makes me feel weird, because they're gone. And it also makes me feel unspecial." "That's the last thing that either Grandma or I would want. You know you're the most special thing to us, don't you?" "I guess so." "The most."

She petted my head for a while, and her fingers went behind my ear to that place that's almost never touched.

I asked if I could zip her dress up again. She said, "Sure," and turned around. She said, "I think it would be good if you tried to go to school." I said, "I am trying." "Maybe if you just went for first period." "I can't even get out of bed." Lie #6. "And Dr. Fein said I should listen to my feelings. He said I should give myself a break sometimes." That wasn't a lie, exactly, although it wasn't exactly the truth, either. "I just don't want it to become a habit," she said. "It won't," I said. When she put her hand on the covers, she must have felt how puffy they were, because she asked if I had my clothes on in bed. I told her, "I do, and the reason is because I am cold." #7. "I mean, in addition to being hot."

As soon as she left, I got my things together and went downstairs. "You look better than yesterday," Stan said. I told him to mind his own business. He said, "Jeez." I told him, "It's just that I'm feeling worse than yesterday."

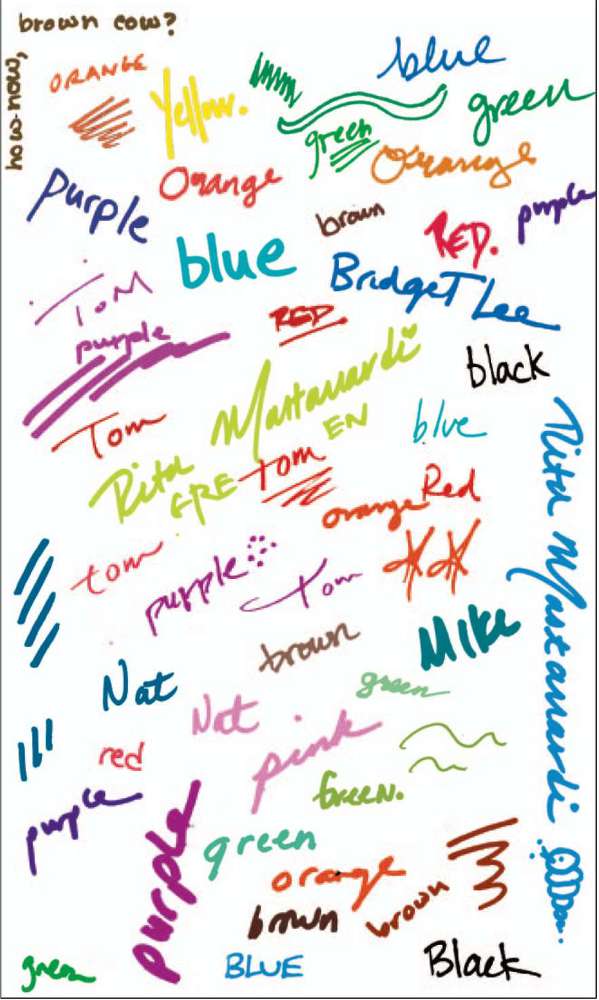

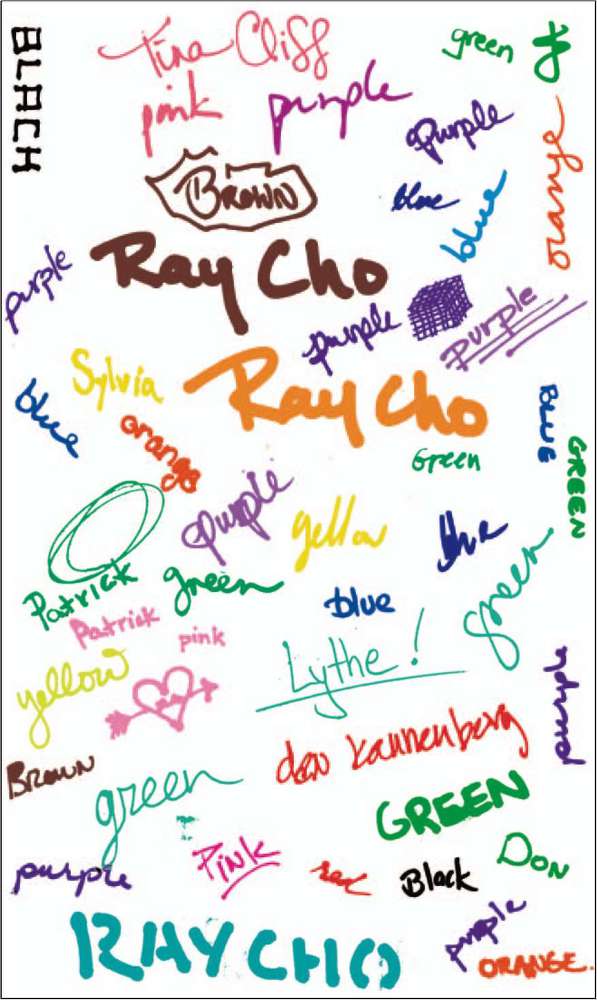

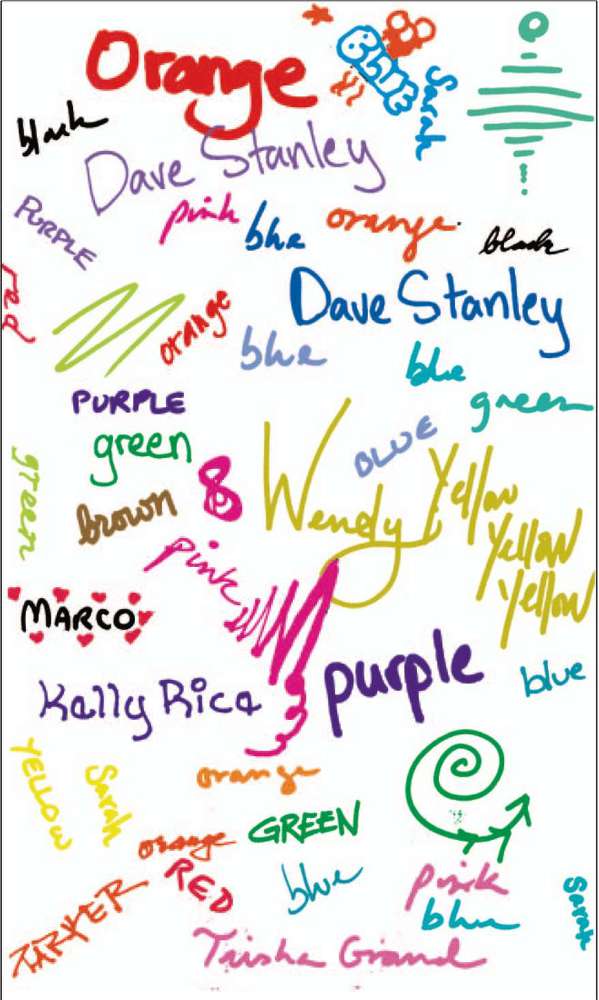

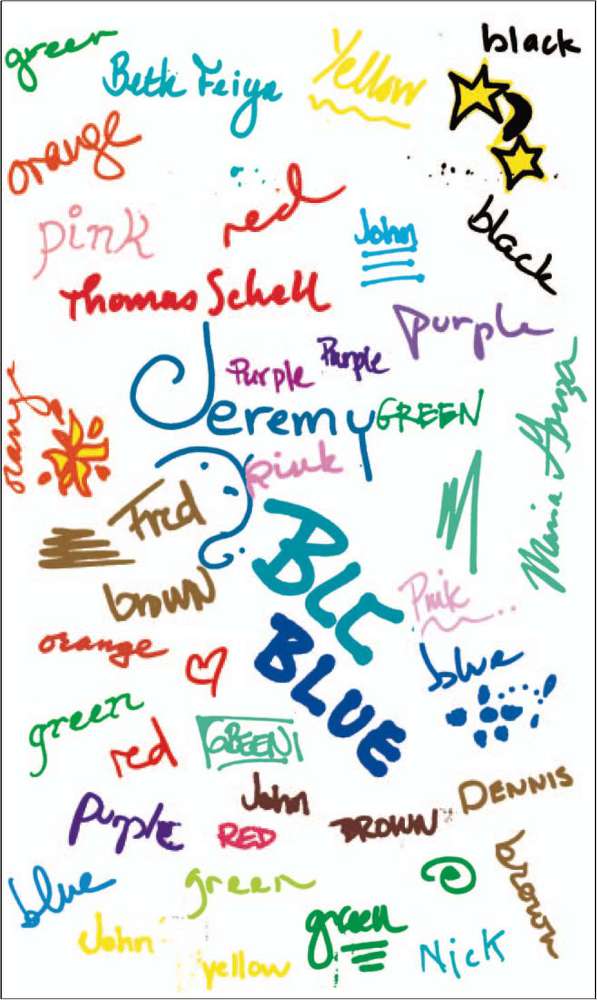

I walked over to the art supply store on Ninety-third Street, and I asked the woman at the door if I could speak to the manager, which is something Dad used to do when he had an important question. "What can I do for you?" she asked. "I need the manager," I said. She said, "I know. What can I do for you?" "You're incredibly beautiful," I told her, because she was fat, so I thought it would be an especially nice compliment, and also make her like me again, even though I was sexist. "Thanks," she said. I told her, "You could be a movie star." She shook her head, like, What the? "Anyway," I said, and I showed her the envelope, and explained how I had found the key, and how I was trying to find the lock it opened, and how maybe black meant something. I wanted to know what she could tell me about black, since she was probably an expert of color. "Well," she said, "I don't know that I'm an expert of anything. But one thing I can say is it's sort of interesting that the person wrote the word 'black' in red pen." I asked why that was interesting, because I just thought it was one of the red pens Dad used when he read the New York Times. "Come here," she said, and she led me to a display of ten pens. "Look at this." She showed me a pad of paper that was next to the display.

"See," she said, "most people write the name of the color of the pen they're writing with." "Why?" "I don't know why. It's just one of those psychological things, I guess." "Psychological is mental?" "Basically." I thought about it, and I had the revelation that if I was testing out a blue pen, I'd probably write the word "blue." "It's not easy to do what your dad did, writing the name of one color with another color. It doesn't come naturally." "Really?" "This is even harder," she said, and she wrote something on the next piece of paper and told me to read it out loud. She was right, it didn't feel natural at all, because part of me wanted to say the name of the color, and part of me wanted to say what was written. In the end I didn't say anything.

I asked her what she thought it meant. "Well," she said, "I don't know that it means anything. But look, when someone tests a pen, usually he either writes the name of the color he's writing with, or his name. So the fact that 'Black' is written in red makes me think that Black is someone's name." "Or her name." "And I'll tell you something else." "Yeah?" "The b is capitalized. You wouldn't usually capitalize the first letter of a color." "Jose!" "Excuse me?" "Black was written by Black!" "What?" "Black was written by Black! I need to find Black!" She said, "If there's anything else I can help you with, just let me know." "I love you." "Would you mind not shaking the tambourine in the store?"

She walked away, and I stayed there for a bit, trying to catch up with my brain. I flipped back through the pad of paper while I thought about what Stephen Hawking would do next.

I ripped the last sheet from the pad and ran to find the manager again. She was helping somebody with paintbrushes, but I thought it wouldn't be rude to interrupt her. "That's my dad!" I told her, putting my finger on his name. "Thomas Schell!" "What a coincidence," she said. I told her, "The only thing is, he didn't buy art supplies." She said, "Maybe he bought art supplies and you didn't know it." "Maybe he just needed a pen." I ran around the rest of the store, from display to display, looking to see if he'd tested any other art supplies. That way I could prove if he had been buying art supplies or just testing out pens to buy a pen.

I couldn't believe what I found.

His name was everywhere. He'd tested out markers and oil sticks and colored pencils and chalk and pens and pastels and watercolors. He'd even scratched his name into a piece of moldable plastic, and I found a sculpting knife with yellow on its end, so I knew that was what he did it with. It was as if he was planning on making the biggest art project in history. But I didn't get it: that had to have been more than a year ago.

I found the manager again. "You said if there was anything else you could help me with, that I should just let you know." She said, "Let me finish with this customer, and then you'll have my full attention." I stood there while she finished with the customer. She turned to me. I said, "You said if there was anything else you could help me with, that I should just let you know. Well, I need to see all of the store's receipts." "Why?" "So I can know what day my dad was here and also what he bought." "Why?" "So I can know." "But why?" "Your dad didn't die, so I won't be able to explain it to you." She said, "Your dad died?" I told her yes. I told her, "I bruise easily." She went over to one of the registers, which was actually a computer, and typed something on the screen with her finger. "How do you spell the name again?" "S. C. H. E. L. L." She pressed some more buttons, and made a face, and said, "Nothing." "Nothing?" "Either he didn't buy anything or he paid cash." "Shiitake, hold on." "Excuse me?" "Oskar Schell ... Hi, Mom ... Because I'm in the bathroom ... Because it was in my pocket ... Uh-huh. Uh-huh. A little, but can I call you back when I'm not going to the bathroom? Like in half an hour? ... That's personal ... I guess ... Uh-huh ... Uh-huh ... OK, Mom ... Yuh ... Bye."