And I wouldn't say no to something sweet

I'm sorry, this is the smallest I've got

Start spreading the news...

The regular, please

Thank you, but I'm about to burst

I'm not sure, but it's late

Help

Ha ha ha!

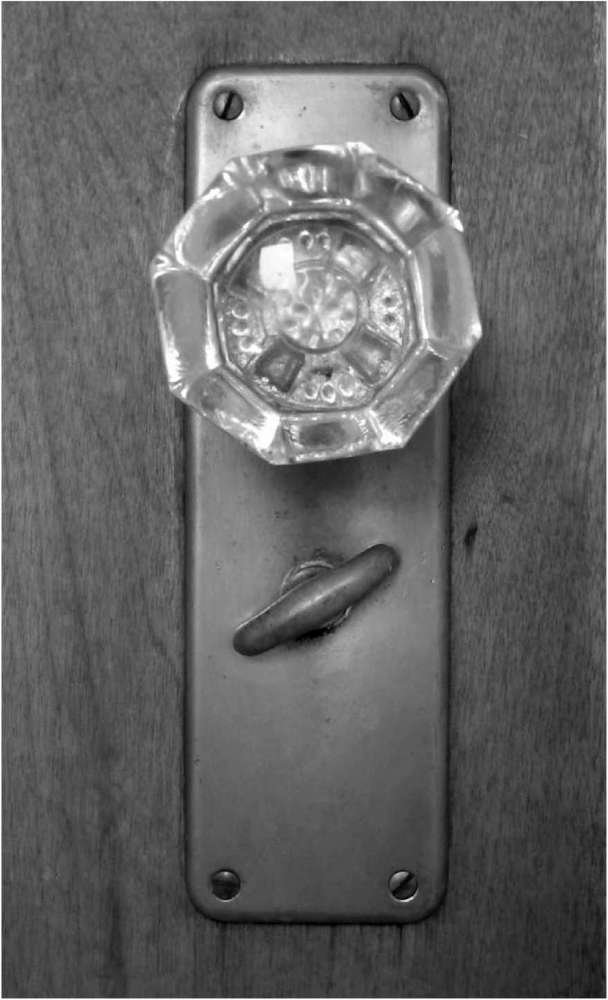

It wasn't unusual for me to run out of blank pages before the end of the day, so should I have to say something to someone on the street or in the bakery or at the bus stop, the best I could do was flip back through the daybook and find the most fitting page to recycle, if someone asked me, "How are you feeling?" it might be that my best response was to point at, "The regular, please," or perhaps, "And I wouldn't say no to something sweet," when my only friend, Mr. Richter, suggested, "What if you tried to make a sculpture again? What's the worst thing that could happen?" I shuffled halfway into the filled book: "I'm not sure, but it's late." I went through hundreds of books, thousands of them, they were all over the apartment, I used them as doorstops and paperweights, I stacked them if I needed to reach something, I slid them under the legs of wobbly tables, I used them as trivets and coasters, to line the birdcages and to swat insects from whom I begged forgiveness, I never thought of my books as being special, only necessary, I might rip out a page—"I'm sorry, this is the smallest I've got"—to wipe up some mess, or empty a whole day to pack up the emergency light bulbs, I remember spending an afternoon with Mr. Richter in the Central Park Zoo, I went weighted down with food for the animals, only someone who'd never been an animal would put up a sign saying not to feed them, Mr. Richter told a joke, I tossed hamburger to the lions, he rattled the cages with his laughter, the animals went to the corners, we laughed and laughed, together and separately, out loud and silently, we were determined to ignore whatever needed to be ignored, to build a new world from nothing if nothing in our world could be salvaged, it was one of the best days of my life, a day during which I lived my life and didn't think about my life at all. Later that year, when snow started to hide the front steps, when morning became evening as I sat on the sofa, buried under everything I'd lost, I made a fire and used my laughter for kindling: "Ha ha ha!" "Ha ha ha!" "Ha ha ha!" "Ha ha ha!" I was already out of words when I met your mother, that may have been what made our marriage possible, she never had to know me. We met at the Columbian Bakery on Broadway, we'd both come to New York lonely, broken and confused, I was sitting in the corner stirring cream into coffee, around and around like a little solar system, the place was half

empty but she slid right up next to me, "You've lost everything," she said, as if we were sharing a secret, "I can see." If I'd been someone else in a different world I'd've done something different, but I was myself, and the world was the world, so I was silent, "It's OK," she whispered, her mouth too close to my ear, "Me too. You can probably see it from across a room. It's not like being Italian. We stick out like sore thumbs. Look at how they look. Maybe they don't know that we've lost everything, but they know something's off." She was the tree and also the river flowing away from the tree, "There are worse things," she said, "worse than being like us. Look, at least we're alive," I could see that she wanted those last words back, but the current was too strong, "And the weather is one hundred dollars, also, don't let me forget to mention," I stirred my coffee. "But I hear it's supposed to get crummy tonight. Or that's what the man on the radio said, anyway," I shrugged, I didn't know what "crummy" meant, "I was gonna go buy some tuna fish at the A&P. I clipped some coupons from the Post this morning. They're five cans for the price of three. What a deal! I don't even like tuna fish. It gives me stomachaches, to be frank. But you can't beat that price," she was trying to make me laugh, but I shrugged my shoulders and stirred my coffee, "I don't know anymore," she said. "The weather is one hundred dollars, and the man on the radio says it's gonna get crummy tonight, so maybe I should go to the park instead, even if I burn easily. And anyway, it's not like I'm gonna eat the tuna fish tonight, right? Or ever, if I'm being frank. It gives me stomachaches, to be perfectly frank. So there's no rush in that department. But the weather, now that won't stick around. Or at least it never has. And I should tell you also that my doctor says getting out is good for me. My eyes are crummy, and he says I don't get out nearly enough, and that if I got out a little more, if I were a little less afraid..." She was extending a hand that I didn't know how to take, so I broke its fingers with my silence, she said, "You don't want to talk to me, do you?" I took my daybook out of my knapsack and found the next blank page, the second to last. "I don't speak," I wrote. "I'm sorry." She looked at the piece of paper, then at me, then back at the piece of paper, she covered her eyes with her hands and cried, tears seeped between her fingers and collected in the little webs, she cried and cried and cried, there weren't any napkins nearby, so I ripped the page from the book—"I don't speak. I'm sorry."—and used it to dry her cheeks, my explanation and apology ran down her face like mascara, she took my pen from me and wrote on the next blank page of my daybook, the final one:

Please marry me

I flipped back and pointed at, "Ha ha ha!" She flipped forward and pointed at, "Please marry me." I flipped back and pointed at, "I'm sorry, this is the smallest I've got." She flipped forward and pointed at, "Please marry me." I flipped back and pointed at, "I'm not sure, but it's late." She flipped forward and pointed at, "Please marry me," and this time put her finger on "Please," as if to hold down the page and end the conversation, or as if she were trying to push through the word and into what she really wanted to say. I thought about life, about my life, the embarrassments, the little coincidences, the shadows of alarm clocks on bedside tables. I thought about my small victories and everything I'd seen destroyed, I'd swum through mink coats on my parents' bed while they hosted downstairs, I'd lost the only person I could have spent my only life with, I'd left behind a thousand tons of marble, I could have released sculptures, I could have released myself from the marble of myself. I'd experienced joy, but not nearly enough, could there be enough? The end of suffering does not justify the suffering, and so there is no end to suffering, what a mess I am, I thought, what a fool, how foolish and narrow, how worthless, how pinched and pathetic, how helpless. None of my pets know their own names, what kind of person am I? I lifted her finger like a record needle and flipped back, one page at a time:

Help

GOOGOLPLEX

As for the bracelet Mom wore to the funeral, what I did was I converted Dad's last voice message into Morse code, and I used sky-blue beads for silence, maroon beads for breaks between letters, violet beads for breaks between words, and long and short pieces of string between the beads for long and short beeps, which are actually called blips, I think, or something. Dad would have known. It took me nine hours to make, and I had thought about giving it to Sonny, the homeless person who I sometimes see standing outside the Alliance Française, because he puts me in heavy boots, or maybe to Lindy, the neat old woman who volunteers to give tours at the Museum of Natural History, so I could be something special to her, or even just to someone in a wheelchair. But instead I gave it to Mom. She said it was the best gift she'd ever received. I asked her if it was better than the Edible Tsunami, from when I was interested in edible meteorological events. She said, "Different." I asked her if she was in love with Ron. She said, "Ron is a great person," which was an answer to a question I didn't ask. So I asked again. "True or false: you are in love with Ron." She put her hand with the ring on it in her hair and said, "Oskar, Ron is my friend." I was going to ask her if she was humping her friend, and if she had said yes, I would have run away, and if she had said no, I would have asked if they heavy-petted each other, which I know about. I wanted to tell her she shouldn't be playing Scrabble yet. Or looking in the mirror. Or turning the stereo any louder than what you needed just to hear it. It wasn't fair to Dad, and it wasn't fair to me. But I buried it all inside me. I made her other Morse code jewelry with Dad's messages—a necklace, an anklet, some dangly earrings, a tiara—but the bracelet was definitely the most beautiful, probably because it was the last, which made it the most precious. "Mom?" "Yes?" "Nothing."