Then she started to cry tears.

I thought, I'm the one who's supposed to be crying.

"Don't cry," I told her. "Why not?" she asked. "Because," I told her. "Because what?" she asked. Since I didn't know why she was crying, I couldn't think of a reason. Was she crying about the elephants? Or something else I'd said? Or the desperate person in the other room? Or something that I didn't know about? I told her, "I bruise easily." She said, "I'm sorry." I told her, "I wrote a letter to that scientist who's making those elephant recordings. I asked if I could be her assistant. I told her I could make sure there were always blank tapes ready for recording, and I could boil all the water so it was safe to drink, or even just carry her equipment. Her assistant wrote back to tell me she already had an assistant, obviously, but maybe there would be a project in the future that we could work on together." "That's great. Something to look forward to." "Yeah."

Someone came to the door of the kitchen who I guessed was the man that had been calling from the other room. He just stuck his head in extremely quickly, said something I didn't understand, and walked away. Abby pretended to ignore it, but I didn't. "Who was that?" "My husband." "Does he need something?" "I don't care." "But he's your husband, and I think he needs something." She cried more tears. I went over to her and I put my hand on her shoulder, like Dad used to do with me. I asked her what she was feeling, because that's what he would ask. "You must think this is very unusual," she said. "I think a lot of things are very unusual," I said. She asked, "How old are you?" I told her twelve—lie #59—because I wanted to be old enough for her to love me. "What's a twelve-year-old doing knocking on the doors of strangers?" "I'm trying to find a lock. How old are you?" "Forty-eight." "Jose. You look much younger than that." She cracked up through her crying and said, "Thanks." "What's a forty-eight-year-old doing inviting strangers into her kitchen?" "I don't know." "I'm being annoying," I said. "You're not being annoying," she said, but it's extremely hard to believe someone when they tell you that.

I asked, "Are you sure you didn't know Thomas Schell?" She said, "I didn't know Thomas Schell," but for some reason I still didn't believe her. "Maybe you know someone else with the first name Thomas? Or someone else with the last name Schell?" "No." I kept thinking there was something she wasn't telling me. I showed her the little envelope again. "But this is your last name, right?" She looked at the writing, and I could see that she recognized something about it. Or I thought I could see it. But then she said, "I'm sorry. I don't think I can help you." "And what about the key?" "What key?" I realized I hadn't even shown it to her yet. All of that talking—about dust, about elephants—and I hadn't gotten to the whole reason I was there.

I pulled the key out from under my shirt and put it in her hand. Because the string was still around my neck, when she leaned in to look at the key, her face came incredibly close to my face. We were frozen there for a long time. It was like time was stopped. I thought about the falling body.

"I'm sorry," she said. "Why are you sorry?" "I'm sorry I don't know anything about the key." Disappointment #3. "I'm sorry, too."

Our faces were so incredibly close.

I told her, "The fall play this fall is Hamlet, in case you're interested. I'm Yorick. We have a working fountain. If you want to come to opening night, it's twelve weeks from now. It should be pretty great." She said, "I'll try," and I could feel the breath of her words against my face. I asked her, "Could we kiss for a little bit?"

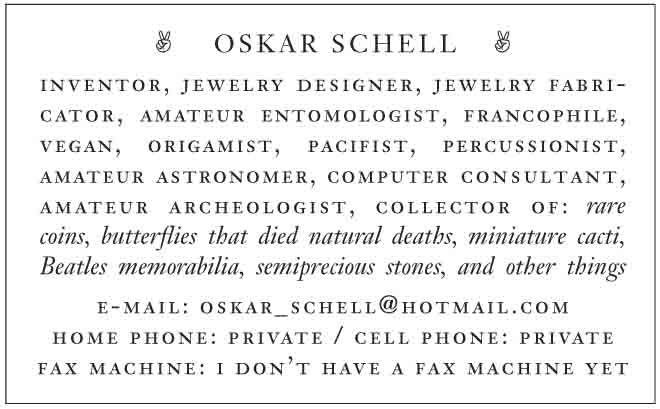

"Excuse me?" she said, although, on the other hand, she didn't pull her head back. "It's just that I like you, and I think I can tell that you like me." She said, "I don't think that's a good idea." Disappointment #4. I asked why not. She said, "Because I'm forty-eight and you're twelve." "So?" "And I'm married." "So?" "And I don't even know you." "Don't you feel like you know me?" She didn't say anything. I told her, "Humans are the only animal that blushes, laughs, has religion, wages war, and kisses with lips. So in a way, the more you kiss with lips, the more human you are." "And the more you wage war?" Then I was the silent one. She said, "You're a sweet, sweet boy." I said, "Young man." "But I don't think it's a good idea." "Does it have to be a good idea?" "I think it does." "Can I at least take a picture of you?" She said, "That would be nice." But when I started focusing Grandpa's camera, she put her hand in front of her face for some reason. I didn't want to force her to explain herself, so I thought of a different picture I could take, which would be more truthful, anyway. "Here's my card," I told her, when the cap was back on the lens, "in case you remember anything about the key or just want to talk."

***

I went over to Grandma's apartment when I got home, which is what I did basically every afternoon, because Mom worked at the firm on Saturdays and sometimes even Sundays, and she got panicky about me being alone. As I got near Grandma's building, I looked up and didn't see her sitting at her window waiting for me, like she always did. I asked Farley if she was there, and he said he thought so, so I went up the seventy-two stairs.

I rang the doorbell. She didn't answer, so I opened the door, because she always leaves it unlocked, even though I don't think that's safe, because sometimes people who seem good end up being not as good as you might have hoped. As I walked in, she was coming to the door. It looked almost like she had been crying, but I knew that was impossible, because once she told me that she emptied herself of tears when Grandpa left. I told her fresh tears are produced every time you cry. She said, "Anyway." Sometimes I wondered if she cried when no one was looking.

"Oskar!" she said, and lifted me from the ground with one of her hugs. "I'm OK," I said. "Oskar!" she said again, picking me up in another hug. "I'm OK," I said again, and then I asked her where she'd been. "I was in the guest room talking to the renter."

When I was a baby, Grandma would take care of me during the day. Dad told me that she would give me baths in the sink, and trim my fingernails and toenails with her teeth because she was afraid of using clippers. When I was old enough to take baths in the bathtub, and to know I had a penis and a scrotum and everything, I asked her not to sit in the room with me. "Why not?" "Privacy." "Privacy from what? From me?" I didn't want to hurt her feelings, because not hurting her feelings is another of my raisons d'être. "Just privacy," I said. She put her hands on her stomach and said, "From me?" She agreed to wait outside, but only if I held a ball of yarn, which went under the bathroom door and was connected to the scarf she was knitting. Every few seconds she would give it a tug, and I had to tug back—undoing what she'd just done—so that she could know I was OK.