On my way out, Stan said, "What a day!" I said, "Yeah." He asked, "What's on the menu?" I showed him the key. He said, "Lox?" I said, "Hilarious, but I don't eat anything with parents." He shook his head and said, "I couldn't help myself. So what's on the menu?" "Queens and Greenwich Village." "You mean Gren-ich Village?" That was my first disappointment of the expedition, because I thought it was pronounced phonetically, which would have been a fascinating clue. "Anyway."

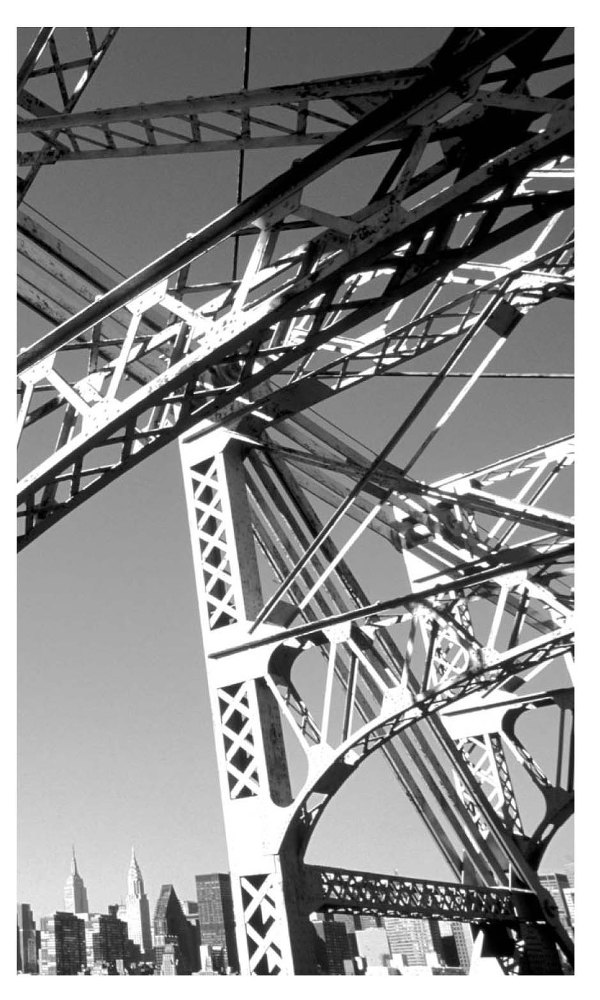

It took me three hours and forty-one minutes to walk to Aaron Black, because public transportation makes me panicky, even though walking over bridges also makes me panicky. Dad used to say that sometimes you have to put your fears in order, and that was one of those times. I walked across Amsterdam Avenue, and Columbus Avenue, and Central Park, and Fifth Avenue, and Madison Avenue, and Park Avenue, and Lexington Avenue, and Third Avenue, and Second Avenue. When I was exactly halfway across the Fifty-ninth Street Bridge, I thought about how a millimeter behind me was Manhattan and a millimeter in front of me was Queens. So what's the name of the parts of New York—exactly halfway through the Midtown Tunnel, exactly halfway over the Brooklyn Bridge, the exact middle of the Staten Island Ferry when it's exactly halfway between Manhattan and Staten Island—that aren't in any borough?

I took a step forward, and it was my first time in Queens.

I walked through Long Island City, Woodside, Elmhurst, and Jackson Heights. I shook my tambourine the whole time, because it helped me remember that even though I was going through different neighborhoods, I was still me. When I finally got to the building, I couldn't figure out where the doorman was. At first I thought maybe he was just getting some coffee, but I waited around for a few minutes and he didn't come. I looked through the door and saw that there was no desk for him. I thought, Weird.

I tried my key in the lock, but it didn't go in past the tip. I saw a device with a button for each apartment, so I pressed the button for A. Black's apartment, which was 9E. No one answered. I pressed it again. Nothing. I held down the buzzer for fifteen seconds. Still nothing. I sat down on the ground and wondered if it would be overly wimpy to cry in the lobby of an apartment building in Corona.

"All right, all right," a voice said from the speaker. "Take it easy." I jumped up. "Hello," I said, "my name is Oskar Schell." "What do you want?" His voice sounded mad, but I hadn't done anything wrong. "Did you know Thomas Schell?" "No." "Are you sure?" "Yes." "Do you know anything about a key?" "What do you want?" "I didn't do anything wrong." "What do you want?" "I found a key," I said, "and it was in an envelope with your name on it." "Aaron Black?" "No, just Black." "It's a common name." "I know." "And a color." "Obviously." "Goodbye," the voice said. "But I'm just trying to find out about this key." "Goodbye." "But—" "Goodbye." Disappointment #2.

I sat back down and started to cry in the lobby of an apartment

building in Corona. I wanted to press all of the buttons and scream curse words at everybody who lived in the stupid building. I wanted to give myself bruises. I stood up and pressed 9E again. This time the voice came out immediately. "What. Do. You. Want?" I said, "Thomas Schell was my dad." "And?" "Was. Not is. He's dead." He didn't say anything, but I knew he was pressing the Talk button because I could hear a beeping in his apartment, and also windows rattling from the same breeze that I was feeling at ground level. He asked, "How old are you?" I said seven, because I wanted him to feel more sorry for me, so he would help me. Lie #34. "My dad's dead," I told him. "Dead?" "He's inanimate." He didn't say anything. I heard more beeping. We just stood there, facing each other, but nine floors apart. Finally he said, "He must have died young." "Yeah." "How old was he?" "Forty." "That's too young." "That's true." "Can I ask how he died?" I didn't want to talk about it, but I remembered the promises I made to myself about my search, so I told him everything. I heard more beeping and wondered if his finger was getting tired. He said, "If you come up, I'll have a look at that key." "I can't go up." "Why not?" "Because you're on the ninth floor and I don't go that high." "Why not?" "It isn't safe." "But it's perfectly safe here." "Until something happens." "You'll be fine." "It's a rule." "I'd come down for you," he said, "but I just can't." "Why not?" "I'm very sick." "But my dad is dead." "I'm hooked up to all sorts of machines. That's why it took me so long to get to the intercom." If I could do it again, I would do it differently. But you can't do it again. I heard the voice saying, "Hello? Hello? Please." I slid my card under the apartment building door and got away from there as fast as I could.

Abby Black lived in #1 in a townhouse on Bedford Street. It took me two hours and twenty-three minutes to walk there, and my hand got exhausted from shaking my tambourine. There was a little sign above the door that said the poet Edna Saint Vincent Millay once lived in the house, and that it was the narrowest house in New York. I wondered if Edna Saint Vincent Millay was a man or a woman. I tried the key, and it went in halfway, but then it stopped. I knocked. No one answered, even though I could hear someone talking inside, and I guessed that #1 meant the first floor, so I knocked again. I was willing to be annoying if that's what was necessary.

A woman opened the door and said, "Can I help you?" She was incredibly beautiful, with a face like Mom's, which seemed like it was smiling even when she wasn't smiling, and huge boobs. I especially liked how her earrings sometimes touched her neck. It made me wish all of a sudden that I'd brought some kind of invention for her, so that she'd have a reason to like me. Even something small and simple, like a phosphorus brooch.

"Hi." "Hello." "Are you Abby Black?" "Yes." "I'm Oskar Schell." "Hello." "Hi." I told her, "I'm sure people tell you this constantly, but if you looked up 'incredibly beautiful' in the dictionary, there would be a picture of you." She cracked up a bit and said, "People never tell me that." "I bet they do." She cracked up a bit more. "They don't." "Then you hang out with the wrong people." "You might be right about that." "Because you're incredibly beautiful."

She opened the door a bit more. I asked, "Did you know Thomas Schell?" "Excuse me?" "Did you know Thomas Schell?" She thought. I wondered why she had to think. "No." "Are you sure?" "Yes." There was something unsure about the way she said she was sure, which made me think that maybe she was keeping some sort of secret from me. So what would that secret be? I handed her the envelope and said, "Does this mean anything to you?" She looked at it for a while. "I don't think so. Should it?" "Only if it does," I told her. "It doesn't," she told me. I didn't believe her.