“That was the weather, not me. I did the best I could.” Flynn grabbed another Kleenex and blew his nose, making a sound like a motorboat. The walls of the kitchen were light yellow. On the wall above the table hung a photograph of Pope John Paul and another of President Kennedy. “Anyway,” continued Flynn, “I’d been looking for this guy all fall. When I found him, he was dead. Sometimes it happens like that. Hey, it saved the state a chunk of change. Two states.”

Flynn was just as glad to get away from the subject of snow chains.

He had arrived home with his cold around three. He’d called in sick, then gone to bed and slept for several hours. When he woke, Junie had made the chicken soup and began preparing the pan of hot water for his feet while he told her about his journey through the snowstorm and what he had found at Bishop’s Hill.

“I never seen snow like that.” Flynn shook his head vigorously to give a sense of the drama. Curley stared up at him with his head tilted, as if trying to construct a rudimentary thought but not quite managing. “It wasn’t like snow down here. This was big-time weather. Snowplow didn’t show up till midnight, with the troopers and ambulance right behind. I ended up sleeping in a dorm—some kid’s room with rock and roll posters on the wall. Electricity never did come on.”

“So why didn’t you come home yesterday? Coughlin said you were supposed to work.” Junie took her coat from the back of a chair. Her club met punctually at eight and it was now past seven-thirty.

“I wanted to talk to this guy Hawthorne. Dr. Hawthorne, they call him. He told me about LaBrecque or LeBrun—I can’t keep the names straight. Like I had part of the story and I wanted the rest. I thought he’d be glad that LaBrecque was dead. But he was more upset about LaBrecque than about those two teachers that got killed. Hawthorne couldn’t stop talking about him. It made me suspicious, but this copper up there said Hawthorne was all right. A little eccentric, that’s all. They call this copper a police chief but he’s only got one guy under him. We had a couple of meals together. I like him. We might even go up there this summer. They got a lake.”

Junie looked skeptical. “I like to take our vacations on the Cape.” She began putting on her coat—dark brown with black buttons and a mink collar. “So everything’s over and done with?”

“As far as Massachusetts is concerned, but New Hampshire’s not off the hook. There’ll be a grand jury investigation and they’ll bring charges against three or four people—a couple of them lawyers. That’ll drag on for a while. Statutory rape, sexual abuse—the whole business. But then a lot of white-collar crime. That Hawthorne’s got his work cut out for him, I can tell you. Give me a good old working-class murder any day of the week. Nothing subtle or too complex. I mean, LaBrecque was a bad guy but he’d been a bad guy from the start. These teachers and lawyers, it’s like they chose to be bad. Like they could pick one or the other and they decided they wanted to be crooks.”

“They all sound the same to me.” Junie tied her scarf around her neck. “I’ll be back by eleven at the latest. Remember—no cigarettes, no beer, be in bed by nine, and keep the cat off the table.” She crossed the kitchen to kiss his cheek. Flynn patted her behind.

“You look nice,” he said.

Junie pursed her lips disapprovingly, then smiled. A moment later she was shutting the front door. Flynn waited about ten seconds, then removed his feet from the pan of water and padded over to the refrigerator, leaving wet footprints on the linoleum. Taking out a half gallon of milk and a bottle of Molson, he opened both, then got a saucer from the cupboard. He set it on the kitchen table and filled it with milk. “Like some milky?” he shouted. Curley had been deaf for years.

Flynn picked up the cat and set it in front of the milk. Then he returned to his chair and opened the window a few inches, letting in a gust of frigid air. Curley was staring at the milk as if he didn’t know if it was meant to be drunk. Flynn scratched the cat under the chin. Black hairs floated down to the table. He would have to clean them up before Junie got home. Taking a pack of Marlboros from the pocket of his bathrobe, Flynn shook one out and lit it with a kitchen match. He inhaled deeply and bent over to blow a cloud of smoke through the partly opened window.

How strange, he thought, still brooding about Bishop’s Hill. If going to prison or getting killed was how you ended up, why would a person choose to be bad?

He thought of LaBrecque’s death again and how upset Hawthorne had been. Why hadn’t he been relieved, getting rid of a guy like that? Hawthorne hadn’t wanted to let LaBrecque stay on the fence till the ambulance came. They had to move the body—first Moulton and himself and Hawthorne, trying to push LaBrecque off the spikes where he was wedged tight, pushing until Flynn thought he was going to bust a gasket. Then they had gotten the other teacher that was hanging around, then this pretty woman, Hawthorne’s girlfriend or something. The five of them pushing and shoving and grunting until LaBrecque had flopped over into the snow.

But there was Hawthorne, standing over the guy looking somber, practically in tears. He was mourning, for Pete’s sake. Who the hell was this LaBrecque to make such a fuss over? Like he had told Junie, LaBrecque had been a bad guy from the start. It was as if LaBrecque had become the person in charge, as if the dead man lying there in the snow was making the rules. But Leo Flynn wasn’t having any of that and so he had turned his back to the bunch of them and looked out at the night sky, where the snow was stopping and the moon was coming out.

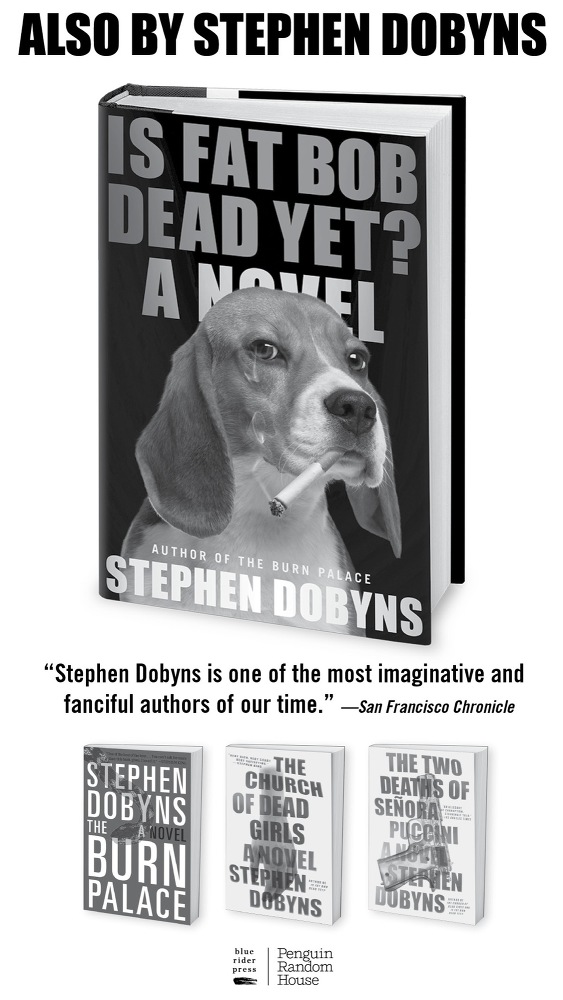

About the Author

Stephen Dobyns is the author of over thirty novels and poetry collections, including The Church of Dead Girls, Cold Dog Soup, Cemetery Nights, and The Burn Palace. Among his many honors and awards are a Melville Cane Award, Pushcart Prizes, National Poetry Series prize, and three National Endowment for the Arts fellowships. His novels have been translated into twenty languages, and his poetry has appeared in the Best American Poems anthology. Dobyns teaches creative writing at Warren Wilson College and has taught at the University of Iowa, Sarah Lawrence College, and Syracuse University.

Looking for more?

Visit Penguin.com for more about this author and a complete list of their books.

Discover your next great read!