“The fact is,” Guillermo says, “that what I do is not fan art. My films are not fan films, even if I am immersed in pop culture. That is just one facet of what I do, what I draw upon, and who I am. I am influenced by literature as much as I am by comics, and by fine art as much as I am by so-called low-brow. But I am not trapped by either extreme. I transit between these parameters in absolute freedom, doing my own thing. I try to present myself as I am, without apologies and with absolute passion and sincerity. I study my subjects and plan my work meticulously. Think of Cronos, Devil’s Backbone, or Pan’s Labyrinth and you will see that what I do is not only to recontextualize artistic forms but reflect on the genres or subgenres that they belong to. I try to deconstruct through love, through appreciation, not by referencing, but by reconnecting the material with its thematic roots in a new approach. The vampire film, the ghost story, and the fairy tale are re-elaborated in my work, rather than just reenacted or imitated. I never want to follow a recipe; I want to cook my own.”

As for Guillermo, he likes to call it his “man cave.”

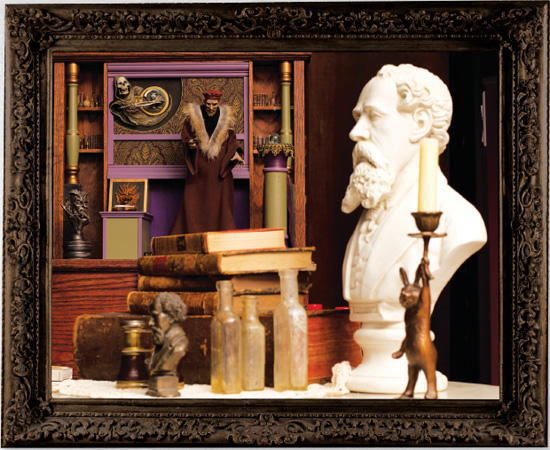

Bleak House is a mixture of predominantly Victorian and Gothic elements by way of Hollywood, with real and imaginary skeletons scattered throughout.

An alcove at Bleak House devoted to Charles Dickens.

I’ve had this feeling three times before in my life.

When I was seven, I visited the Ackermansion, Forrest J Ackerman’s stupendous collection of monster and sci-fi memorabilia. Uncle Forry’s home was filled with articulated dinosaurs from King Kong, the latex alien hand from The Thing, Spock’s pointed ears, original art by Frank R. Paul and Virgil Finlay, a copy of the robot from Metropolis, and thousands of other items. The second time was when I was in my early twenties and literally crawling through Rod Serling’s attic while researching my book The Twilight Zone Companion. The attic housed heavy leather volumes holding every article and snippet printed about Serling, files with notions finished and unfinished, a box full of unproduced Twilight Zone scripts, and plastic airplane models still in their boxes. The third time was when I visited Ray Bradbury’s canary-yellow house in Cheviot Hills, which overflowed with mementos and touchstones from his miraculous life. From original Joe Mugnaini artwork for Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles to the toy typewriter he’d first started writing on at age twelve, everywhere there was wonder.

“Never throw out anything you love,” Ray said on many occasions. In each of these homes, a brilliant man’s head and heart had seemingly exploded to fill a house, inviting visitors to scrutinize, linger, and be nourished. But Guillermo’s house, by dint of sheer passion and obsession, tops them all.

Guillermo charmingly refers to Bleak House as his “collection of strange crap.” In a more serious mood, he adds, “You’re God as an artist, and it’s really just the way you arrange. I think a director is an arranger. I direct this house, and everything goes somewhere, and I can tell you why, and there are thematic pairings, or there is a wall with all blue on it. There is nothing accidental. And my movies are like my house. I hang every painting, and if the frame shows a clock or a watch, or shows an apple, or shows a piece of furniture, I chose that, and I ask the art director and the production designer to show it to me before, and I walk the set and I say, ‘Take this out’ or ‘Bring this in.’ It really is the beauty of the director, I think, in the way I understand the craft.”

On that first visit, Guillermo led me deeper into the house. I was agog at the cinematic, literary, artistic, and zoological feast—akin to the food piled high to tempt Ofelia at the Pale Man’s table in Pan’s Labyrinth. Wandering Bleak House is a Through the Looking-Glass experience, as if one has actually stepped into one of Guillermo’s films.

Through glass doors leading to the backyard, I spied the life-size bronze of Ray Harryhausen, one of Guillermo’s spiritual godfathers. Then we turned down a hallway lined with wild art, gleaming weird mechanisms—some insectile, others mechanical—tin toys, Pez dispensers, anatomical models, and a miniature of the Time Machine from the eponymous 1960 film by George Pal, another member of Guillermo’s pantheon. Hovering as if in benediction, now tied permanently to a wall as he’d once been strapped to Ron Perlman’s back in Hellboy, was the torso and head of the Russian corpse, a role voiced in the movie by Guillermo himself. Just off the hall were the How to Look at Art volumes that started it all, and at the end of the corridor, in a glass case, was the first Pirates of the Caribbean model Guillermo so lovingly assembled and painted as a child.

And then the pièce de résistance. Like a character out of Poe or Dickens, Arthur Machen or M. R. James, or any of the legion of outré writers of whom Guillermo is an acolyte, my host beckoned me to enter his sanctum sanctorum, the room where Guillermo writes his scripts at a big old wood desk or, more often, on the overstuffed leather sofa. Best of all, at the flick of a switch, lightning flashed, thunder rumbled, and rain cascaded down false windows looking onto endless night.

We settled into the leather sofa and began to talk.

A LIFE FULL OF WONDER

In fashioning his house, Guillermo credits Forrest J Ackerman as a key inspiration, but there is another guiding principle that predates Ackerman and gives a deeper meaning to Bleak House.

Call it Guillermo del Toro’s cabinet of curiosities.

After all, everything surrounding this fabulous, larger-than-life character, from his films to his house to his notebooks to his speaking engagements, is chock-full of extravagant, peculiar, and extraordinary items—his world is an overflowing credenza of marvelous things. Further, the term’s provenance makes it particularly fitting.

Originally, cabinet of curiosities referred to a personal collection of spectacular, eclectic, and outlandish objects accumulated by a wealthy person, often an aristocrat. Also known in German as wunderkammer (“wonder room”) and kunstkammer (“art room”), these “cabinets” were not pieces of furniture but entire rooms full to bursting with every unusual and attractive bauble that could be found in the natural world or realms constructed by humanity. Hitting their peak of popularity in the seventeenth century and spurred by the discovery of the New World, these cabinets might house clockwork automata, Chinese porcelain, the crown of Montezuma, a madonna made of feathers, chains of monkey teeth, a rhinoceros horn and tail, conjoined twins, a mermaid’s hand, a dragon’s egg, real or supposed holy relics, vials of blood that had rained from the sky, an elephant head with tusks, carved indigenous canoes, an entire crocodile hanging from the ceiling, a two-headed cat, and as one list concluded, “anything that is strange.”

At the time, science had not yet developed standardized methods of classification, and museums had not yet been established for public consumption, so these cabinets of curiosities grew at the whims of their owners in bizarre and breathtaking ways, each its own deformed, magnificent, unique universe.

Sporting titles redolent of their times, those famous for their cabinets included the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, Archduke of Austria Ferdinand II, Peter the Great, Augustus II the Strong, King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, John Tradescant the elder, Elias Ashmole, and the deliciously named Ole Worm.