To me, Böcklin is perfect proof that art does not reproduce the world; it creates a new one.

ODILON REDON (1840–1916)

Most art movements are comprised of such a variety of artists and techniques that it becomes difficult to define the borders that separate one from the next, or the qualities that fuse them into a movement in the first place. If you think of Schwabe, Böcklin, or most of the other painters associated with the symbolist movement, you’ll evoke a sense of realism. By way of contrast, Redon’s diffuse pastels and line work seem weightless and luminous—sometimes almost abstract. Both his technique and concerns remain unique amongst his peers. He is the sublime anomaly.

Even so, Redon was part of a more general movement amongst painters working at the end of the nineteenth century to turn away from technical realism and to begin to value the strength of a brushstroke, the immediacy of an emotion. But these new values were typically developed with respect to the outside world, whereas only Redon looks to the inside.

Distinctive motifs in Redon’s work are: the feather, the eye, prisons and bars, botanical shapes, feathery line work reminiscent of animal fur, and spidery forms with human faces—every one of these comes straight from the id and a sense of pagan frenzy. If one needs any persuasion to find a strong connection between the Surrealists, the Dadaists, and the symbolists, one doesn’t need to look any further than Redon. Most of his images go beyond the pagan contemplation of Böcklin or Schwabe and become iconic, striving to capture not only the essence of a symbol but its direct link to the human psyche. Jungian and Freudian images populate his work and remain elusive, slippery, and hellish, but then his color work has a nimble, vital energy that captures mystic rapture and the true light of paradise.

After I die, if there is life beyond this one and I go anywhere—either up or down—I am pretty sure that both places will be art directed by Redon.

CARLOS SCHWABE (1866–1926)

The two artists who inspired me most while working on Pan’s Labyrinth and Hellboy II: The Golden Army were Schwabe and Arthur Rackham. Their interpretations of the fairy world are not at all similar, but both men seem to approach it as explorers attempting to document a world only revealed to their eyes.

Schwabe did splendid graphic work based on texts by Zola, Mallarmé, and Baudelaire, but his drawings, etchings, and paintings should not be regarded as mere illustrations for these works. Each one of them is suffused with a mystical energy and with pantheistic conviction.

In this day and age, we confuse hip smartness that does not fully endorse any idea with intelligence, and consider callousness the product of an experienced point of view of the world. Naturally, this attitude leads us to value artists who seem to know it all. But Schwabe and the rest of the symbolists were the exact opposite: They celebrated not knowing, the twilight of our knowledge. To them, the supernatural was absolutely real, and mystery was the supreme goal of art.

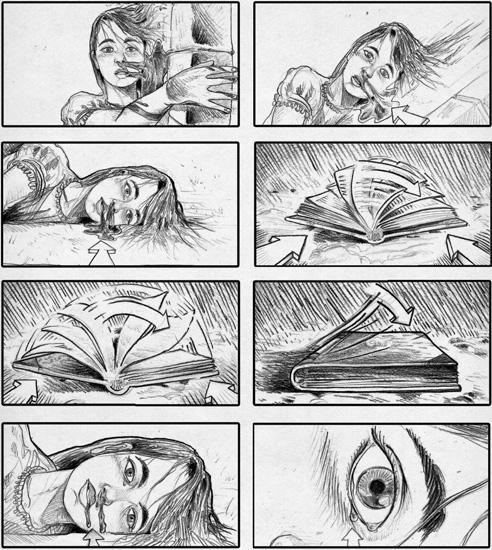

According to del Toro, one of the great mysteries of cinema is its ability to reverse time, a technique he employs at the beginning of Pan’s Labyrinth, depicted here in storyboards by Raúl Monge.

ANALYZING FILM

MSZ: One very distinctive quality about your film work is that it’s enormously tactile, textural, lyrical. There’s a sense that every moment, every image, is handmade, as if you’re sculpting every shot. Viewers can revisit your films over and over again.

GDT: Well, if they want to. I do put a lot in the audiovisual coding of a movie. Some is rational, but then another 50 percent is instinctive—the way you arrange things. I think a director is an arranger. Alien is the perfect example. It’s an absolutely mind-boggling feat of filmmaking. People can say, “Oh, well, it’s Giger.” No, it’s not Giger because Giger was a painter before Ridley Scott called him up to sculpt and design.

And lest we forget, Scott grouped him with Moebius [Jean Giraud], Ron Cobb, Chris Foss, and Roger Christian. Each of those men brought a syntax, but Scott created the context. I think that’s what directing is—saying, “I’m going to use this photographer, and I’m going to use this musician.” It’s a fantastic feat. Directing is the orchestration and the arrangement of images and sounds and also of people and talents.

Del Toro on the set of Hellboy II with Hellboy’s gun, The Good Samaritan.

MSZ: When you see films that come out well, behind them is a process in which ideas have become better and better, whereas with bad films it’s the exact opposite—they just get worse and worse, progressively.

GDT: Well, but you never know. You never know. You have no idea. If we knew what our destiny is, we would be great. Everybody would be great. What I do think is that there is a myth—the myth of the director as this inflexible creature that has it all figured out from the get-go, as if they are a mechanical master who arranges everything perfectly.

Some people can point to Stanley Kubrick, and I’ll tell you this: The more I read about him and the more I talk to people who worked with him, it’s only mostly true. He had 80 percent of it figured out. But the 20 percent that he didn’t have figured out, he found—through the same process that every director uses, which is finding perfection in compromise. Because you compromise with the weather, you compromise with the schedule, you compromise with the budget, you compromise with the fact that an actor is sick. You’re figuring it out. You are reorganizing. You don’t necessarily say, “I cannot take this out because the movie will be compromised.” At some point you might have to, but not always.

I remember very clearly an anecdote about Kirk Douglas having an accident during one of Kubrick’s movies. I think it was Paths of Glory, but it could have been Spartacus. The anecdote I read was that he was out of commission for over a week, and he got a letter from Kubrick, or a phone call, and Kubrick said, “Could you claim that you’re still not able to work so I can get a few more days? Because I’m just figuring the movie out.” Or take James Cameron, who is arguably one of the most precise filmmakers in the world and the smartest, most disciplined artist I have ever met. The myth is that he is an inhumanly precise filmmaking machine. But the beauty of Jim is that he is all too human. I’ve seen him toil and sweat and, in the middle of the night, ask himself, “What do I do here? What do I do there?” That’s the beauty and power of it: Jim is human but he demands more of himself than anyone else.

Why enthrone the myth of the perfect, infallible superhuman if it’s always more beautiful to know that the humanity that creates beauty is the same fallible species that can create horror or misery? Bach, when explaining his genius, used to modestly say that he just worked harder and that all you have to do is press the pedals on the keyboard and the notes play themselves. Here you have one of the greatest geniuses ever and yet this was a guy that had personal flaws of one kind or another and who created in the face of self-doubt and adversity.

I always say it’s more interesting to think that the pyramids were built not by aliens but by people. People go, “Oh, they’re extraordinary things. They were built by aliens.” No, the extraordinary thing is that they were built by people. Normal people.