“Come in,” she said. “I’ve been so worried. God, where’ve you been?”

“It’s a long story,” he said. “Can’t it wait till morning?”

“It can’t wait until morning,” she said, closing the door. She sniffed. “You smell heavenly, Brother,” she said sarcastically. “And you look as though you’ve just been laid.”

“I’m a gentleman,” Rudolph said, trying to make light of the accusation. “Gentlemen don’t discuss matters like that.”

“Ladies do,” she said. She had her vulgar side, Gretchen.

“Let’s drop it, please,” he said. “I need some sleep. What’s so damned urgent?”

Gretchen fell back into a big armchair, sprawling, as though she were too tired to stand anymore. “Bunny Dwyer called an hour ago,” she said flatly. “Wesley’s in jail.”

“What?”

“Wesley’s in jail in Cannes. He got into a fight in a bar and nearly killed a man with a beer bottle. He hit a cop and the police had to subdue him. Is that urgent enough for you, Brother?”

A Biography of Irwin Shaw

Irwin Shaw (1913–1984) was an award-winning American novelist, playwright, screenwriter, and short story writer. His novel The Young Lions (1948) is considered a classic of World War II fiction. From the early pages of the New Yorker to the bestseller lists, Shaw earned a reputation as a leading literary voice of his generation.

Shaw was born Irwin Shamforoff in the Bronx, New York, on February 27, 1913. His parents, Will and Rose, were Russian Jewish immigrants and his father struggled as a haberdasher. The family moved to Brooklyn and barely survived the Depression. After graduating from high school at the age of sixteen, Shaw worked his way through Brooklyn College, where he started as quarterback on the school’s scrappy football team.

“Discovered” by a college teacher (who later got him his first assignment, writing for the Dick Tracy radio serials), Shaw became a household name at the age of twenty-two thanks to his first produced play, Bury the Dead. This 1935 Broadway hit—still regularly produced around the world—is a bugle call against profit-driven barbarity. Offered a job as a Hollywood staff scriptwriter, Shaw then contributed to numerous Golden Era films such as The Big Game (1936) and The Talk of the Town (1942). While continuing to write memorable stories for the New Yorker, he also penned The Gentle People (1939), a play that was adapted for film four different times.

World War II altered the course of Shaw’s career. Refusing a commission, he enlisted in the army, and was shipped off to North Africa as a private in a photography unit in 1943. After the North African campaign, he served in London during the preparations for the invasion of Normandy. After D-Day, Shaw and his unit followed the front lines and documented many of the most important moments of the war, including the liberations of Paris and the Dachau concentration camp.

The Young Lions (1948), his epic novel, follows three soldiers—two Americans and one German—across North Africa, Europe, and into Germany. Along with James Jones’s From Here to Eternity, Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, and The Caine Mutiny by Herman Wouk, The Young Lions stands as one of the great American novels of World War II. In 1958, it was made into a film starring Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift.

In 1951, wrongly suspected of Communist sympathies, Shaw moved to Europe with his wife and six-month-old son. In Paris, he was neighbors with journalist Art Buchwald and friends with the great French writers, photographers, actors, and moviemakers of his generation, including Joseph Kessel, Robert Capa, Simone Signoret, and Louis Malle. In Rome, Shaw gave author William Styron his wedding lunch, doctored screenplays, walked with director Federico Fellini on the Via Veneto, and got the idea for his novel Two Weeks in Another Town (1960).

Finally, he settled in the small Swiss village of Klosters and continued writing screenplays, stage plays, and novels. Rich Man, Poor Man (1970) and Beggerman, Thief (1977) were made into the first famous television miniseries. Nightwork (1975) will soon be a major motion picture. Shaw died in the shadow of the Swiss peaks that had inspired Thomas Mann’s great novel The Magic Mountain.

Shaw as a young soldier crossing North Africa from Algiers to Cairo in 1943.

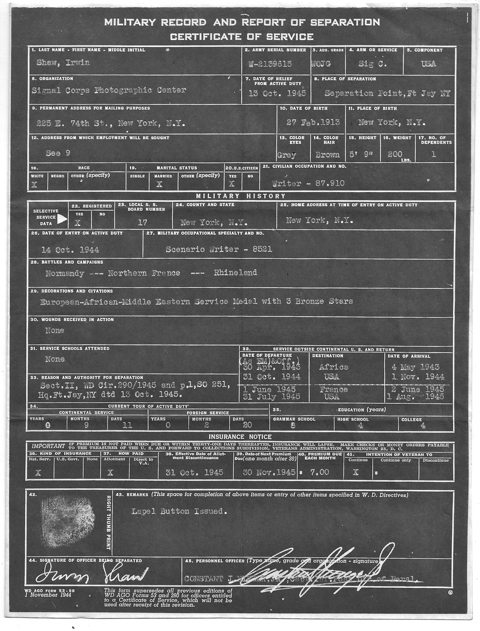

Shaw’s US Army record.

Shaw just after D-Day in Normandy, France, in 1944.

A few weeks after D-Day, Shaw and his Signal Corps film crew liberate Mont Saint-Michel.

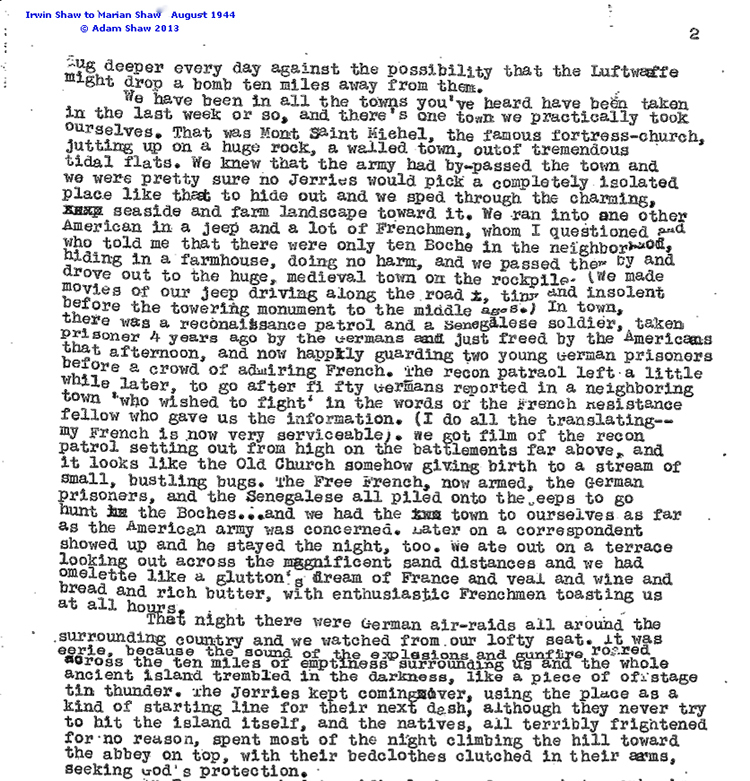

A 1944 letter from Shaw to his wife, Marian, describing the “taking” of Mont Saint-Michel, as well as a nerve-wracking night under a cathedral when he almost shot a group of monks, believing them to be Germans.

Shaw as a warrant-officer in Austria in 1945, with Signal Corps Captain Josh Logan (left) and Colonel Anatole Litvak (center), who became his lifelong friends.

Shaw, Marian, and their son, Adam, on the terrace of the newly built Chalet Mia in Klosters, Switzerland, in 1957.

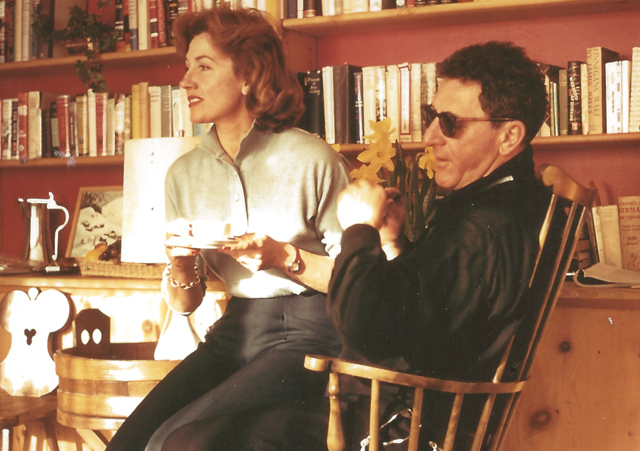

Shaw at home with Marian at Chalet Mia, Klosters, in 1958.

Shaw (center) skiing in Klosters in 1960 with (left to right) Noel Howard (an actor), an unidentified Hollywood producer, Marian Shaw, Jacques Charmoz (a French World War II pilot, cartoonist, and painter), and Jacqueline Tesseron.

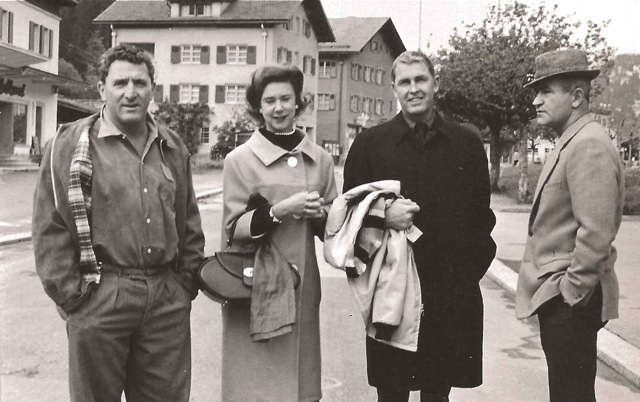

Shaw in Klosters in 1960 with (from left to right) Kathy Parrish, her husband Robert Parrish (an Academy Award–winning film editor and director), and Peter Viertel (a screenwriter, novelist, and Shaw’s coauthor for the play The Survivors). Shaw’s friendship with Viertel started before the war, when they both lived in Malibu.

Shaw with Irving P. “Swifty” Lazar, the legendary talent agent who represented him, in Evian, France, in 1963.

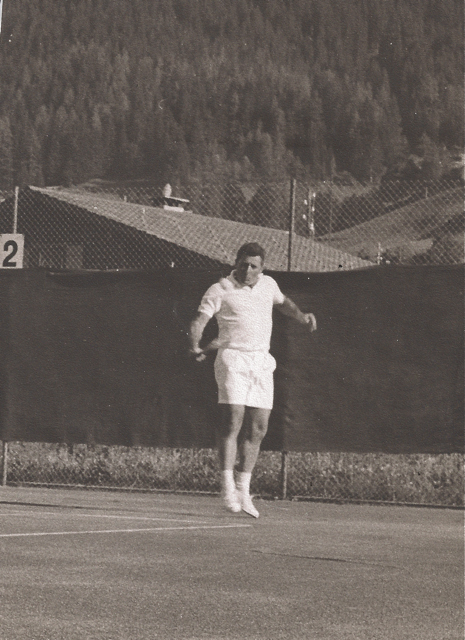

Shaw playing tennis in Klosters in 1964.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.