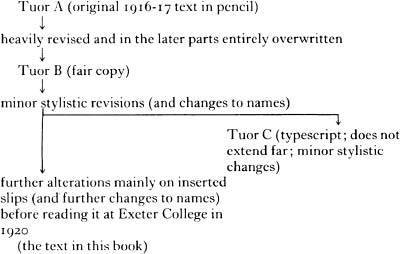

Subsequently my father took his pencil to Tuor B, emending it fairly heavily, though mostly in the earlier part of the tale, and almost entirely for stylistic rather than narrative reasons; but these emendations, as will be seen, were not all made at the same time. Some of them are written out on separate slips, and of these several have on their reverse sides parts of an etymological discussion of certain Germanic words for the Butcherbird or Shrike, material which appears in the Oxford Dictionary in the entry Wariangle. Taken with the fact that one of the slips with this material on the reverse clearly contains a direction for the shortening of the tale when delivered orally (see note 21), it is virtually certain that a good deal of the revision of Tuor B was made before my father read it to the Essay Club of Exeter College in the spring of 1920 (see Unfinished Tales p. 5).

That not all the emendations to Tuor B were made at the same time is shown by the existence of a typescript (Tuor C), without title, which extends only so far as ‘your hill of vigilance against the evil of Melko’ (p. 161). This was taken from Tuor B when some changes had been made to it, but not those which I deduce to have been made before the occasion when it was read aloud. An odd feature of this text is that blanks were left for many of the names, and only some were filled in afterwards. Towards the end of it there is a good deal of independent variation from Tuor B, but it is all of a minor character and none has narrative significance. I conclude that this was a side-branch that petered out.

The textual history can then be represented thus:

Since the narrative itself underwent very little change of note in the course of this history (granted that substantial parts of the original text Tuor A are almost entirely illegible), the text that follows here is that of Tuor B in its final form, with some interesting earlier readings given in the Notes. It seems that my father did not check the fair copy Tuor B against the original, and did not in every case pick up the errors of transcription it contains; when he did, he emended them anew, according to the sense, and not by reference back to Tuor A. In a very few cases I have gone back to Tuor A where this is clearly correct (as ‘a wall of water rose nigh to the cliff-top’, p. 151, where Tuor B and the typescript Tuor C have ‘high to the cliff-top’).

Throughout the typescript Tuor is called Tыr. In Tuor B the name is sometimes emended from Tuor to Tыr in the earlier part of the tale (it appears as Tыr in the latest revisions), but by no means in every case. My father apparently decided to change the name but ultimately decided against it; and I give Tuor throughout.

An interesting document accompanies the Tale: this is a substantial though incomplete list of names (with explanations) that occur in it, now in places difficult or impossible to read. The names are given in alphabetical order but go only as far as L. Linguistic information from this list is incorporated in the Appendix on Names, but the head-note to the list may be cited here:

Here is set forth by Eriol at the teaching of Bronweg’s son Elfrith [emended from Elfriniel] or Littleheart (and he was so named for the youth and wonder of his heart) those names and words that are used in these tales from either the tongue of the Elves of Kфr as at that time spoken in the Lonely Isle, or from that related one of the Noldoli their kin whom they wrested from Melko.

Here first are they which appear in The Tale of Tuor and the Exiles of Gondolin, first among these those ones in the Gnome-speech.

In Tuor A appear two versions (one struck out) of a short ‘preface’ to the tale by Littleheart which does not appear in Tuor B. The second version reads:

Then said Littleheart son of Bronweg: ‘Now the story that I tell is of the Noldoli, who were my father’s folk, and belike the names will ring strange in your ears and familiar folk be called by names not before heard, for the Noldoli speak a curious tongue sweet still to my ears though not maybe to all the Eldar. Wise folk see it as close kin to Eldarissa, but it soundeth not so, and I know nought of such lore. Wherefore will I utter to you the right Eldar names where there be such, but in many cases there be none.

Know then,’ said he, ‘that

The earlier version (headed ‘Link between Tuor and tale before’) begins in the same way but then diverges:

…and it is sweet to my ears still, though lest it be not so to all else of Eldar and Men here gathered I will use no more of it than I must, and that is in the names of those folk and things whereof the tale tells but for which, seeing they passed away ere ever the rest of the Eldar came from Kфr, the Elves have no true names. Know then,’ said he, ‘that Tuor

This ‘preface’ thus connects to the opening of the tale. There here appears, in the second version, the name Eldarissa for the language of the Eldar or Elves, as opposed to Noldorissa (a term found in the Name-list); on the distinction involved see I.50–1. With Littleheart’s words here compare what Rъmil said to Eriol about him (I.48):

‘“Tongues and speeches,” they will say, “one is enough for me” and thus said Littleheart the Gong-warden once upon a time: “Gnome-speech,” said he, “is enough for me—did not that one Eдrendel and Tuor and Bronweg my father (that mincingly ye miscall Voronwл) speak it and no other?” Yet he had to learn the Elfin in the end, or be doomed either to silence or to leave Mar Vanwa Tyaliйva…’

After these lengthy preliminaries I give the text of the Tale.

Tuor and the Exiles of Gondolin

(which bringeth in the great tale of Eдrendel)

Then said Littleheart son of Bronweg: ‘Know then that Tuor was a man who dwelt in very ancient days in that land of the North called Dor Lуmin or the Land of Shadows, and of the Eldar the Noldoli know it best.

Now the folk whence Tuor came wandered the forests and fells and knew not and sang not of the sea; but Tuor dwelt not with them, and lived alone about that lake called Mithrim, now hunting in its woods, now making music beside its shores on his rugged harp of wood and the sinews of bears. Now many hearing of the power of his rough songs came from near and far to hearken to his harping, but Tuor left his singing and departed to lonely places. Here he learnt many strange things and got knowledge of the wandering Noldoli, who taught him much of their speech and lore; but he was not fated to dwell for ever in those woods.

Thereafter ’tis said that magic and destiny led him on a day to a cavernous opening down which a hidden river flowed from Mithrim. And Tuor entered that cavern seeking to learn its secret, but the waters of Mithrim drove him forward into the heart of the rock and he might not win back into the light. And this, ’tis said, was the will of Ulmo Lord of Waters at whose prompting the Noldoli had made that hidden way.

Then came the Noldoli to Tuor and guided him along dark passages amid the mountains until he came out in the light once more, and saw that the river flowed swiftly in a ravine of great depth with sides unscalable. Now Tuor desired no more to return but went ever forward, and the river led him always toward the west.6

The sun rose behind his back and set before his face, and where the water foamed among many boulders or fell over falls there were at times rainbows woven across the ravine, but at evening its smooth sides would glow in the setting sun, and for these reasons Tuor called it Golden Cleft or the Gully of the Rainbow Roof, which is in the speech of the Gnomes Glorfalc or Cris Ilbranteloth.