Thou kept’st a wife herself, thyself a maid.

Of that and all the progress more and less

Resolvèdly more leisure shall express.

All yet seems well; and if it end so meet,

The bitter past, more welcome is the sweet.

Flourish of trumpets

Epilogue

The King’s a beggar now the play is done.

All is well ended if this suit be won:

That you express content, which we will pay

With strife to please you, day exceeding day.

Ours be your patience then, and yours our parts:

Your gentle hands lend us, and take our hearts.

Exeunt

PERICLES

BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE AND GEORGE WILKINS A RECONSTRUCTED TEXT

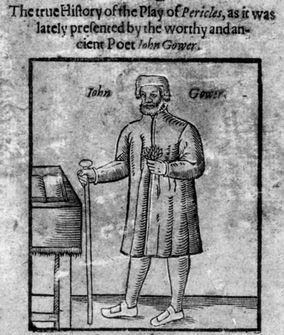

ON 20 May 1608 Pericles was entered on the Stationers’ Register to Edward Blount; but he did not publish it. Probably the players allowed him to license it in the hope of preventing its publication by anyone else, for it was one of the most popular plays of the period. Its success was exploited, also in 1608, by the publication of a novel, by George Wilkins, ‘The Painful Adventures of Pericles Prince of Tyre, Being the True History of the Play of Pericles, as it was lately presented by the worthy and ancient poet John Gower’. The play itself appeared in print in the following year, with an ascription to Shakespeare, but in a manifestly corrupt text that gives every sign of having been put together from memory. This quarto was several times reprinted, but the play was not included in the 1623 Folio (perhaps because Heminges and Condell knew that Shakespeare was responsible for only part of it).

In putting together The Painful Adventures, Wilkins drew on an earlier version of the tale, The Pattern of Painful Adventures, by Laurence Twine, written in the mid-1570s and reprinted in 1607. Twine’s book is also a source of the play, which draws too on the story of Apollonius of Tyre as told by John Gower in his Confessio Amantis, and, to a lesser extent, on Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia. Wilkins not only incorporated verbatim passages from Twine’s book, he also drew heavily on Pericles itself. Since the play text is so corrupt, it is quite likely that Wilkins reports parts of it both more accurately and more fully than the quarto. And he may have had special qualifications for doing so. He was a dramatist whose popular play The Miseries of Enforced Marriage had been performed by Shakespeare’s company. Pericles has usually been regarded as either a collaborative play or one in which Shakespeare revised a pre-existing script. Our edition is based on the hypothesis (not new) that Wilkins was its joint author. Our attempt to reconstruct the play draws more heavily than is usual on Wilkins’s novel, especially in the first nine scenes (which he probably wrote); in general, because of its obvious corruption, the original text is more freely emended than usual. So that readers may experience the play as originally printed, an unemended reprint of the 1609 quarto is given in our original-spelling edition. The deficiencies of the text are in part compensated for by the survival of an unusual amount of relevant visual material, reproduced overleaf.

The complex textual background of Pericles should not be allowed to draw attention away from the merits of this dramatic romance, which we hope will be more apparent as the result of our treatment of the text. If the original play had survived, it might well have been as highly valued as The Winter’s Tale or The Tempest; as it is, it contains some hauntingly beautiful episodes, above all that in Scene 21 in which Marina, Pericles’ long-lost daughter, draws him out of the comatose state to which his sufferings have reduced him.

14. From the title-page of The Painful Adventures of Pericles Prince of Tyre (1608), by George Wilkins; artist unknown. Since Gower is not a character in Wilkins’s novel, the choice of woodcut undoubtedly reflects both the play’s popularity and Gower’s own impact in early performances, and it is as likely to reflect the visual detail of performance as any early title-page. The sprig of laurel (or posy) in Gower’s left hand is symbolic of his poetic status.

15. From Greene’s Vision (1592), sig. CIr―CIv; probably by Robert Greene. The description here fits reasonably well the Painful Adventures title-page, though the woodcut does not contain the ‘bag of red’, ‘napkin’, or tight-fitting ‘breech’.

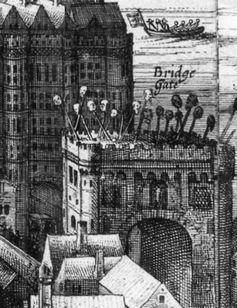

16. Severed heads displayed on the gate of London Bridge, from an etching by Claes Jan Visscher (1616). In the play’s sources, and Painful Adventures, the heads of previous suitors (Sc. 1) are placed on the ’gate’ of Antioch. In performance they could have been thrust out on poles from the upper stage; but the timing and method of their display is not clear.

17. From The Heroical Devices of M. Claudius Paradin, translated by P.S. (1591), sig. V3. This is the source for the impresa of the Third Knight, in Sc. 6.

18. From The Heroical Devices of M. Claudius Paradin, translated by P.S. (1591), sig. Z3. This is the source for the impresa of the Fourth Knight, in Sc. 6.

19. An Inigo Jones sketch of Diana, probably for Ben Jonson’s masque Time Vindicated (1623). The goddess of chastity appeared as a character in court entertainments, masques, and plays, and her representation was governed by iconographic convention. As goddess of hunting, she was most often identified by her ‘silver bow’ (21.234). In Thomas Heywood’s The Golden Age (1611), stage directions refer to ‘Diana’s bow’ (sig. EIv) and her ‘buskins’ (sig. E3v); her ‘nymphs’ explicitly, and by inference she, have ‘garlands on their heads, and javelins in their hands ... bows and quivers’ (sig. D3v). The bow, quiver, and javelin, all visible in Jones’s sketch, were commonplace in emblematic representations. As a huntress, Diana could naturally be envisaged in a chariot: in Aurelian Townshend’s masque Albion’s Triumph (1631), she descends ‘in her chariot’ (pp. 2, 12); in Time Vindicated, ‘Diana descends’ (1. 446). Such descents for deities were used in the public theatres, too, usually in a chair or chariot (21.224.2).