Must not be measured by his worth, for then

It hath no end.

SIWARD

Had he his hurts before?

ROSS

Ay, on the front.

SIWARD

Why then, God’s soldier be he.

Had I as many sons as I have hairs

I would not wish them to a fairer death;

And so his knell is knolled.

MALCOLM

He’s worth more sorrow,

And that I’ll spend for him.

SIWARD

He’s worth no more.

They say he parted well and paid his score,

And so God be with him. Here comes newer comfort.

Enter Macduff with Macbeth’s head

MACDUFF (to Malcolm)

Hail, King, for so thou art. Behold where stands

Th’usurper’s cursed head. The time is free.

I see thee compassed with thy kingdom’s pearl,

That speak my salutation in their minds,

Whose voices I desire aloud with mine:

Hail, King of Scotland!

ALL BUT MALCOLM

Hail, King of Scotland!

Flourish

MALCOLM

We shall not spend a large expense of time

Before we reckon with your several loves

And make us even with you. My thanes and kinsmen,

Henceforth be earls, the first that ever Scotland

In such an honour named. What’s more to do

Which would be planted newly with the time,

As calling home our exiled friends abroad,

That fled the snares of watchful tyranny,

Producing forth the cruel ministers

Of this dead butcher and his fiend-like queen-

Who, as ‘tis thought, by self and violent hands

Took off her life—this and what needful else

That calls upon us, by the grace of grace

We will perform in measure, time, and place.

So thanks to all at once, and to each one,

Whom we invite to see us crowned at Scone.

Flourish. Exeunt Omnes

ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA

FIRST printed in the 1623 Folio, Antony and Cleopatra had been entered on the Stationers’ Register on 20 May 1608. Echoes of it in Barnabe Barnes’s tragedy The Devil’s Charter, acted by Shakespeare’s company in February 1607, suggest that Shakespeare wrote his play no later than 1606, and stylistic evidence supports that date.

The Life of Marcus Antonius in Sir Thomas North’s translation of Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans (1579) was one of the sources for Julius Caesar; it also provided Shakespeare with most of his material for Antony and Cleopatra, in which he draws upon its language to a remarkable extent even in some of the play’s most poetic passages. For example, Enobarbus’ famous description of Cleopatra in her barge (2.2.197-225) incorporates phrase after phrase of North’s prose. And the play’s action stays close to North’s account, though with significant adjustments, particularly compressions of the time-scheme. It opens in 40 BC, two years after the end of Julius Caesar, and portrays events that took place over a period of ten years. Mark Antony has become an older man, though Octavius is still ‘scarce-bearded’. Plutarch, who was a connoisseur of human behaviour, also afforded many hints for the characterization; but some characters, particularly Antony’s comrade Domitius Enobarbus and Cleopatra’s women, Charmian and Iras, are largely created by Shakespeare.

In the earlier play, Mark Antony had formed a triumvirate with Octavius Caesar and Lepidus. In Antony and Cleopatra the triumvirate is in a state of disintegration, partly because Mark Antony—married at the play’s opening to Fulvia, who is rebelling against Octavius Caesar—is infatuated with Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt (and the former mistress of Julius Caesar). The play’s action swings between Rome and Alexandria as Antony is torn between the claims of Rome—strengthened for a while by his marriage, after Fulvia’s death, to Octavius Caesar’s sister Octavia—and the temptations of Egypt. Gradually opposition between Antony and Octavius increases, until they engage in a sea-fight near Actium (in Greece), in which Antony follows Cleopatra’s navy in ignominious retreat. The closing stages of the double tragedy portray Antony’s shame, humiliation, and suicide after Cleopatra falsely causes him to believe that she has killed herself; faced with the threat that Caesar will take her captive to Rome, Cleopatra too commits suicide. According to Plutarch, she was thirty-eight years old; as for Antony, ‘some say that he lived three-and-fifty years, and others say, six-and-fifty’.

In Antony and Cleopatra the classical restraint of Julius Caesar gives way to a fine excess of language, of dramatic action, and of individual behaviour. The style is hyperbolical, overflowing the measure of the iambic pentameter. The action is amazingly fluid, shifting with an ease and rapidity that caused bewilderment to ages unfamiliar with the conventions of Shakespeare’s theatre. And the characterization is correspondingly extravagant, delighting in the quirks of individual behaviour, above all in the paradoxes and inconsistencies of the Egyptian queen who contains within herself the capacity for every extreme of human behaviour, from vanity, meanness, and frivolity to the sublime self-transcendence with which she faces and embraces death.

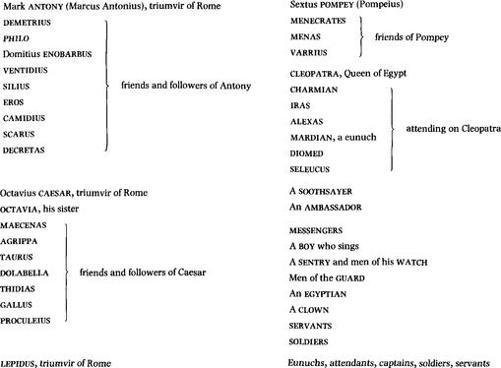

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

The Tragedy of Antony and Cleopatra

1.1 Enter Demetrius and Philo

PHILO

Nay, but this dotage of our General’s

O‘erflows the measure. Those his goodly eyes,

That o’er the files and musters of the war

Have glowed like plated Mars, now bend, now turn

The office and devotion of their view

Upon a tawny front. His captain’s heart,

Which in the scuffles of great fights hath burst

The buckles on his breast, reneges all temper,

And is become the bellows and the fan

To cool a gipsy’s lust.

Flourish. Enter Antony, Cleopatra, her ladies, the train, with eunuchs fanning her

Look where they come.

Take but good note, and you shall see in him

The triple pillar of the world transformed

Into a strumpet’s fool. Behold and see.

CLEOPATRA (to Antony)

If it be love indeed, tell me how much.

ANTONY

There’s beggary in the love that can be reckoned.

CLEOPATRA

I’ll set a bourn how far to be beloved.