And we’ll strive to please you every day.

Exit

TROILUS AND CRESSIDA

Troilus and Cressida, first heard of in a Stationers’ Register entry of 7 February 1603, was probably written within the previous eighteen months. This entry did not result in publication; the play was re-entered on 28 January 1609, and a quarto appeared during that year. The version printed in the 1623 Folio adds a Prologue, and has many variations in dialogue. It includes the epilogue spoken by Pandarus (which we print as an Additional Passage), but certain features of the text suggest that it does so by accident, and that the epilogue had been marked for omission. Our text is based in substance on the Folio in the belief that this represents the play in its later, revised form.

The story of the siege of Troy was the main subject of one of the greatest surviving works of classical literature, Homer’s Iliad, probably Shakespeare read George Chapman’s 1598 translation of Books 1―2 and 7―11. The story also figures prominently in Virgil’s Aeneid and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, both of which Shakespeare knew well. The war between Greece and Troy had been provoked by the abduction of the Grecian Helen (better, if confusingly, known as Helen of Troy) by the Trojan hero Paris, son of King Priam. Shakespeare’s play opens when the Greek forces, led by Menelaus’ brother Agamemnon, have already been besieging Troy for seven years. Shakespeare concentrates on the opposition between the Greek hero Achilles and the Trojan Hector. In the Folio, Troilus and Cressida is printed among the tragedies; if there is a tragic hero, it is Hector.

Shakespeare also shows how the war caused by one love affair destroys another. The stories of the love between the Trojan Troilus and the Grecian Cressida, encouraged by her uncle Pandarus, and of Cressida’s desertion of Troilus for the Greek Diomedes, are medieval additions to the heroic narrative. Chaucer’s long poem Troilus and Criseyde was already a classic, and Shakespeare would also have known Robert Henryson’s continuation, The Testament of Cresseid, in which Cressida, deserted by Diomedes, dwindles into a leprous beggar.

Troilus and Cressida is a demanding play, Shakespeare’s third longest, highly philosophical in tone and with an exceptionally learned vocabulary. Possibly (as has often been conjectured) he wrote it for private performance; the 1603 Stationers’ Register entry says it had been acted by the King’s Men, and the original title-page of the 1609 quarto repeats this claim, but while the edition was being printed this title-page was replaced by one that does not mention performance, and an epistle was added claiming that it was ‘a new play, never staled with the stage, never clapper-clawed with the palms of the vulgar’. An adaptation by John Dryden of 1679 was successfully acted from time to time for half a century, but the first verified performance of Shakespeare’s play was in Germany in 1898, and that was heavily adapted. Troilus and Cressida came into its own in the twentieth century, when its deflation of heroes, its radical questioning of human values (especially in relation to love and war), and its remorseless examination of the frailty of human aspirations in the face of the destructive powers of time seemed particularly apposite to modern intellectual and ethical preoccupations.

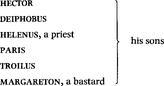

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

PROLOGUE

Trojans

PRIAM, King of Troy

CASSANDRA, Priam’s daughter, a prophetess

ANDROMACHE, wife of Hector

PANDARUS, a lord

CRESSIDA, his niece

CALCHAS, her father, who has joined the Greeks

HELEN, wife of Menelaus, now living with Paris

ALEXANDER, servant of Cressida

Servants of Troilus, musicians, soldiers, attendants

Greeks

AGAMEMNON, Commander-in-Chief

MENELAUS, his brother

NESTOR

ULYSSES

ACHILLES

PATROCLUS, his companion

DIOMEDES

AJAX

THERSITES

MYRMIDONS, soldiers of Achilles

Servants of Diomedes, soldiers

Troilus and Cressida

Prologue Enter the Prologue armed

PROLOGUE

In Troy there lies the scene. From isles of Greece

The princes orgulous, their high blood chafed,

Have to the port of Athens sent their ships,

Fraught with the ministers and instruments

Of cruel war. Sixty-and-nine, that wore

Their crownets regal, from th‘Athenian bay

Put forth toward Phrygia, and their vow is made

To ransack Troy, within whose strong immures

The ravished Helen, Menelaus’ queen,

With wanton Paris steeps—and that’s the quarrel.

To Tenedos they come,

And the deep-drawing barques do there disgorge

Their warlike freightage; now on Dardan plains

The fresh and yet unbruisèd Greeks do pitch

Their brave pavilions. Priam’s six-gated city—

Dardan and Timbria, Helias, Chetas, Troien,

And Antenorides—with massy staples

And corresponsive and full-filling bolts

Spar up the sons of Troy.

Now expectation, tickling skittish spirits

On one and other side, Trojan and Greek,

Sets all on hazard. And hither am I come,

A Prologue armed—but not in confidence

Of author’s pen or actor’s voice, but suited

In like conditions as our argument—

To tell you, fair beholders, that our play

Leaps o’er the vaunt and firstlings of those broils,

Beginning in the middle, starting thence away

To what may be digested in a play.

Like or find fault; do as your pleasures are;

Now, good or bad, ’tis but the chance of war.

Exit

1.1 Enter Pandarus, and Troilus armed

TROILUS

Call here my varlet. I’ll unarm again.