ADDITIONAL PASSAGES

The Dauphin/Bourbon variant, which usually involves only the alteration of speech-prefixes, has several consequences for the dialogue and structure of 4.5. There follow edited texts of the Folio and Quarto versions of this scene.

A. FOLIO

Enter the Constable, Orleans, Bourbon, the Dauphin, and Rambures

CONSTABLE O diable!

ORLÉANS O Seigneur! Le jour est perdu, tout est perdu.

DAUPHIN

Mort de ma vie! All is confounded, all.

Reproach and everlasting shame

Sits mocking in our plumes.

A short alarum

O méchante fortune! Do not run away.

⌈Exit Rambures⌉

CONSTABLE Why, all our ranks are broke.

DAUPHIN

O perdurable shame! Let’s stab ourselves:

Be these the wretches that we played at dice for?

ORLÉANS

Is this the king we sent to for his ransom?

BOURBON

Shame, an eternall shame, nothing but shame!

Let us die in pride. In once more, back again!

And he that will not follow Bourbon now,

Let him go home, and with his cap in hand

Like a base leno hold the chamber door,

Whilst by a slave no gentler than my dog

His fairest daughter is contaminated.

CONSTABLE

Disorder that hath spoiled us, friend us now,

Let us on heaps go offer up our lives.

ORLÉANS

We are enough yet living in the field

To smother up the English in our throngs,

If any order might be thought upon.

BOURBON

The devil take order now. I’ll to the throng.

Let life be short, else shame will be too long.

Exeunt

B. QUARTO

Enter the four French lords: the Constable, Orléans, Bourbon, and Gebon

GEBON O diabello!

CONSTABLE Mort de ma vie!

ORLÉANS O what a day is this!

BOURBON

O jour de honte, all is gone, all is lost.

CONSTABLE We are enough yet living in the field

To smother up the English,

If any order might be thought upon.

BOURBON

A plague of order! Once more to the field!

And he that will not follow Bourbon now,

Let him go home, and with his cap in hand,

Like a base leno hold the chamber door,

Whilst by a slave no gentler than my dog

His fairest daughter is contaminated.

CONSTABLE

Disorder that hath spoiled us, right us now.

Come we in heaps, we’ll offer up our lives

Unto these English, or else die with fame.

⌈BOURBON⌉ Come, come along.

Let’s die with honour, our shame doth last too long.

Exeunt

JULIUS CAESAR

ON 21 September 1599 a Swiss doctor, Thomas Platter, saw what can only have been Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar ‘very pleasingly performed’ in the newly built Globe Theatre—‘the straw-thatched house’—on the south side of the Thames. Francis Meres does not mention the play in Palladis Tamia of 1598, and minor resemblances with works printed in the early part of 1599 suggest that Shakespeare wrote it during that year. It was first printed in the 1623 Folio.

Julius Caesar shows Shakespeare turning from English to Roman history, which he had last used in Titus Andronicus and The Rape of Lucrece. Caesar was regarded as perhaps the greatest ruler in the history of the world, and his murder by Brutus as one of the foulest crimes: but it was also recognized that Caesar had faults and Brutus virtues. Other plays, some now lost, had been written about Caesar and may have influenced Shakespeare; but there is no question that he made extensive use (for the first time in this play) of Sir Thomas North’s great translation (based on Jacques Amyot’s French version and published in 1579) of Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans by the Greek historian Plutarch, who lived from about AD 50 to 130.

Shakespeare was interested in the aftermath of Caesar’s death as well as in the events leading up to it, and in the public and private motives of those responsible for it. So, although the Folio calls the play The Tragedy of Julius Caesar, Caesar is dead before the play is half over; Brutus, Cassius, and Antony have considerably longer roles, and Brutus is portrayed with a degree of introspection which links him more closely to Shakespeare’s other tragic heroes. Shakespeare draws mainly on the last quarter of Plutarch’s Life of Caesar, showing his fall; he also uses the Lives of Antony and Brutus for the play’s first sweep of action, showing the rise of the conspiracy against Caesar, its leaders’ efforts to persuade Brutus to join them, the assassination itself, and its immediate aftermath as Antony incites the citizens to revenge. The second part, showing the formation of the triumvirate of Antony, Lepidus, and Octavius Caesar, the uneasy alliance of Brutus and Cassius, and the battles in which Caesar’s spirit revenges itself, depends mainly on the Life of Brutus. Facts are often altered and rearranged in the interests of dramatic economy and effectiveness.

Although Shakespeare wrote the play at a point in his career at which he was tending to use a high proportion of prose, Julius Caesar is written mainly in verse; as if to suit the subject matter, the style is classical in its lucidity and eloquence, reaching a climax of rhetorical effectiveness in the speeches over Caesar’s body (3.2). The play’s stage-worthiness has been repeatedly demonstrated; it offers excellent opportunities in all its main roles, and the quarrel between Brutus and Cassius (4.2) has been admired ever since Leonard Digges, a contemporary of Shakespeare, praised it at the expense of Ben Jonson:

So have I seen, when Caesar would appear,

And on the stage at half-sword parley were

Brutus and Cassius; O, how the audience

Were ravished, with what wonder they went thence,

When some new day they would not brook a line

Of tedious though well-laboured Catiline.

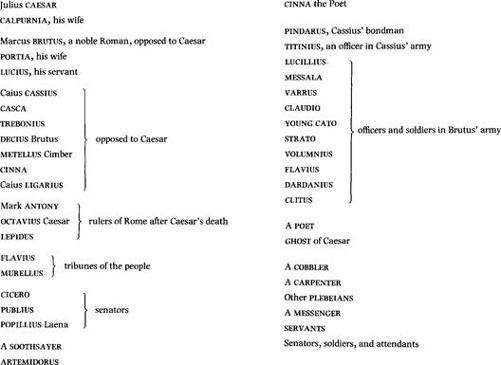

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

1.1 Enter Flavius, Murellus, and certain commoners over the stage

FLAVIUS

Hence, home, you idle creatures, get you home!

Is this a holiday? What, know you not,

Being mechanical, you ought not walk

Upon a labouring day without the sign