FORD Marry, sir, we’ll bring you to Windsor, to one Master Brooke, that you have cozened of money, to whom you should have been a pander. Over and above that you have suffered, I think to repay that money will be a biting affliction.

PAGE Yet be cheerful, knight. Thou shalt eat a posset tonight at my house, where I will desire thee to laugh at my wife that now laughs at thee. Tell her Master Slender hath married her daughter.

MISTRESS PAGE (aside) Doctors doubt that! If Anne Page be my daughter, she is, by this, Doctor Caius’s wife.

Enter Master Slender

SLENDER Whoa, ho, ho, father Page!

PAGE Son, how now? How now, son? Have you dispatched?

SLENDER Dispatched? I’ll make the best in Gloucestershire know on’t; would I were hanged, la, else.

PAGE Of what, son?

SLENDER I came yonder at Eton to marry Mistress Anne Page, and she’s a great lubberly boy. If it had not been i‘th’ church, I would have swinged him, or he should have swinged me. If I did not think it had been Anne Page, would I might never stir; and ’tis a postmaster’s boy.

PAGE Upon my life, then, you took the wrong.

SLENDER What need you tell me that? I think so, when I took a boy for a girl. If I had been married to him, for all he was in woman’s apparel, I would not have had him.

PAGE Why, this is your own folly. Did not I tell you how you should know my daughter by her garments?

SLENDER I went to her in white and cried ‘mum’, and she cried ‘budget’, as Anne and I had appointed; and yet it was not Anne, but a postmaster’s boy.

MISTRESS PAGE Good George, be not angry. I knew of your purpose, turned my daughter into green, and indeed she is now with the Doctor at the deanery, and there married.

Enter Doctor Caius

CAIUS Ver is Mistress Page? By Gar, I am cozened! I ha’ married un garçon, a boy, un paysan, by Gar. A boy! It is not Anne Page, by Gar. I am cozened.

PAGE Why, did you take her in green?

CAIUS Ay, be Gar, and ’tis a boy. Be Gar, I’ll raise all Windsor.

FORD This is strange. Who hath got the right Anne?

Enter Master Fenton and Anne

PAGE

My heart misgives me: here comes Master Fenton.—

How now, Master Fenton?

ANNE

Pardon, good father. Good my mother, pardon.

PAGE

Now, mistress, how chance you went not with Master Slender?

⌈MISTRESS⌉ PAGE

Why went you not with Master Doctor, maid?

FENTON

You do amaze her. Hear the truth of it.

You would have married her, most shamefully,

Where there was no proportion held in love.

The truth is, she and I, long since contracted,

Are now so sure that nothing can dissolve us.

Th’offence is holy that she hath committed,

And this deceit loses the name of craft,

Of disobedience, or unduteous title,

Since therein she doth evitate and shun

A thousand irreligious cursed hours

Which forced marriage would have brought upon her.

FORD (to Page and Mistress Page)

Stand not amazed. Here is no remedy.

In love the heavens themselves do guide the state;

Money buys lands, and wives are sold by fate.

SIR JOHN I am glad, though you have ta’en a special stand to strike at me, that your arrow hath glanced.

PAGE

Well, what remedy? Fenton, heaven give thee joy I

What cannot be eschewed must be embraced.

SIR JOHN

When night-dogs run, all sorts of deer are chased.

MISTRESS PAGE

Well, I will muse no further. Master Fenton,

Heaven give you many, many merry days!

Good husband, let us every one go home,

And laugh this sport o’er by a country fire,

Sir John and all.

FORD Let it be so, Sir John.

To Master Brooke you yet shall hold your word,

For he tonight shall lie with Mistress Ford. Exeunt

2 HENRY IV

2 Henry IV, printed in 1600 as The Second Part of Henry the Fourth, was not reprinted until it was included in somewhat revised form in the 1623 Folio, with the same title. Shakespeare may have started to write it in 1597, directly after I Henry IV, but have laid it aside while he composed The Merry Wives of Windsor. As in I Henry IV, he drew on The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth, Holinshed’s Chronicles, and Samuel Daniel’s Four Books of the Civil Wars, along with other, minor sources; but the play contains a greater proportion of non-historical material apparently invented by Shakespeare. In this play Shakespeare seems from the start to have accepted the change of Sir John’s surname to Falstaff which had been enforced upon him in I Henry IV.

Like I Henry IV, Part Two draws on the techniques of comedy, but its overall tone is more sombre. At its start, the Prince seems to have regressed from his reformed state at the end of Part One; his father still has many causes for anxiety, has not made his expiatory pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and is again the victim of rebellion, led this time by the Earl of Northumberland, the Archbishop of York, and the Lords Hastings and Mowbray. Again Henry’s public responsibilities are exacerbated by anxieties about Prince Harry’s behaviour; the climax of their relationship comes after Harry, discovering his sick father asleep and thinking him dead, tries on his crown; after bitterly upbraiding him, Henry accepts his son’s assertions of good faith, and, recalling the devious means by which he himself came to the throne, warns Harry that he may need to protect himself against civil strife by pursuing ‘foreign quarrels’-the campaigning against France depicted in Henry V. The King dies in the Jerusalem Chamber of Westminster Abbey, the closest he will get to the Holy Land.

In this play the Prince spends less time than in Part One with Sir John, who is shown much in the company of Mistress Quickly and Doll Tearsheet at the Boar’s Head tavern in Eastcheap and later in Gloucestershire on his way to and from the place of battle. Shakespeare never excelled the bitter-sweet comedy of the passages involving Falstaff and his old comrade Justice Shallow. The play ends in a counterpointing of major and minor keys as the newly crowned Henry V rejects Sir John and all that he has stood for.

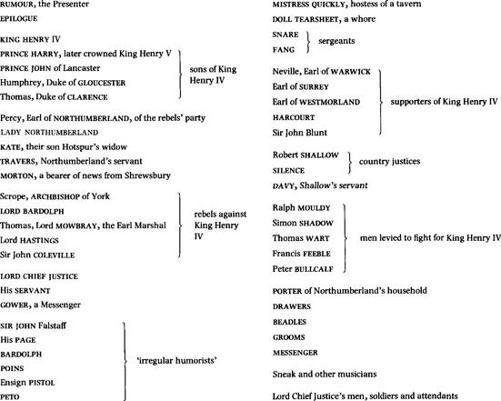

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

The Second Part of Henry the Fourth

Induction Enter Rumour ⌈in a robe⌉ painted full of tongues

RUMOUR

Open your ears; for which of you will stop

The vent of hearing when loud Rumour speaks?

I from the orient to the drooping west,

Making the wind my post-horse, still unfold

The acts commenced on this ball of earth.

Upon my tongues continual slanders ride,