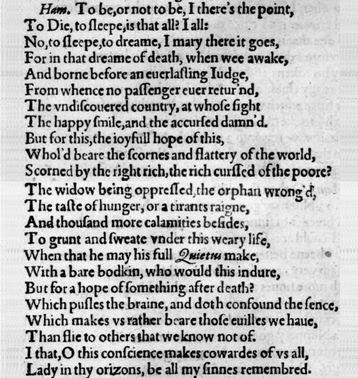

11. ‘To be or not to be’ as it appeared in the ‘bad’ quarto of 1603

Although in general, companies which owned play scripts preferred not to allow them to be printed, some of Shakespeare’s plays were printed from authentic manuscripts during his lifetime, and even while they were still being performed by his company; these have often been designated as ‘good’ quartos. First came Titus Andronicus, printed in 1594 from Shakespeare’s own papers, probably because the company for which he wrote it had been disbanded. In 1597 Richard II was printed perhaps directly from Shakespeare’s manuscript, minus the politically sensitive episode (in 4.1) in which Richard gives up his crown to Bolingbroke: a clear instance of censorship, whether self-imposed or not. The first play to be published from the outset in Shakespeare’s name is Love’s Labour’s Lost, in 1598. Several other quartos printed from good manuscripts appeared around the same time: I Henry IV (probably from a scribal transcript) in 1598, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, 2 Henry IV, and Much Ado About Nothing (all evidently from Shakespeare’s papers) in 1600. In 1604 appeared a new text of Hamlet printed from Shakespeare’s own papers and declaring itself to be ‘Newly imprinted and enlarged to almost as much again as it was, according to the true and perfect copy’: surely an attempt to replace a bad text by a good one. King Lear followed, in 1608, in a badly printed quarto whose status has been much disputed, but which we believe to derive from Shakespeare’s own manuscript. In 1609 came Troilus and Cressida, probably from Shakespeare’s own papers, in an edition which in the first-printed copies claims to present the play ‘as it was acted by the King’s majesty’s servants at the Globe‘, but in copies printed later in the print-run declares that it has never been ‘staled with the stage’. The only new play to appear between Shakespeare’s death and the publication of the Folio in 1623 was Othello, printed in 1622 apparently from a transcript of Shakespeare’s own papers.

Not much money was to be made from printing a single edition of a play, but some of these quartos were several times reprinted. In the right circumstances Shakespeare could be a valuable property to a publisher. He and his company, however, would have benefited only from the one-off return of selling a manuscript for publication. It is not clear why they released reliable texts of some plays but not others. As a shareholder in the company to which the plays belonged, Shakespeare himself must have been a partner in its decisions, and it is difficult to believe that he was so lacking in personal vanity that he was happy to be represented in print by garbled texts; but he seems to have taken no interest in the progress of his plays through the press, and only two plays, Romeo and Juliet and Hamlet, were printed in debased quartos that were replaced with fuller quarto texts. Even some of those printed from authentic manuscripts—such as the 1604 Hamlet—are badly printed, and certainly not proof-read by the author; none of them bears an author’s dedication or shows any sign of having been prepared for the press in the way that, for instance, Ben Jonson clearly prepared some of his plays. John Marston, introducing the printed text of his play The Malcontent in 1604, wrote: ‘Only one thing afflicts me, to think that scenes invented merely to be spoken, should be enforcively published to be read.’ Perhaps Shakespeare was similarly afflicted.

In 1616, the year of Shakespeare’s death, Ben Jonson published his own collected plays in a handsome Folio. It was the first time that an English writer for the popular stage had been so honoured (or had so honoured himself), and it established a precedent by which Shakespeare’s fellows could commemorate their colleague and friend. Principal responsibility for this ambitious enterprise was undertaken by John Heminges and Henry Condell, both long-established actors with Shakespeare’s company; latterly, Heminges had been its business manager. They, along with Richard Burbage, had been the colleagues whom Shakespeare remembered in his will: he left each of them 26s. 8d. to buy a mourning ring. Although the Folio did not appear until 1623, they may have started planning it soon after—or even before—Shakespeare died: big books take a long time to prepare. And they undertook their task with serious care. Most importantly, they printed eighteen plays that had not so far appeared in print, and which might otherwise have vanished. Their decision not to include Edward III suggests at least that they did not believe Shakespeare to have written all of it. They omitted (so far as we can tell) only Pericles, Cardenio (now vanished), The Two Noble Kinsmen—perhaps because these three were collaborative—and the mysterious Love’s Labour’s Won (see p. 337). And they went to considerable pains to provide good texts. They had no previous experience as editors; they may have had help from others (including Ben Jonson, who wrote commendatory verses for the Folio): anyhow, although printers find it easier to set from print than from manuscript, they were not content simply to reprint quartos whenever they were available. In fact they seem to have made a conscious effort to identify and to avoid making use of the quartos now recognized as unauthoritative. In their introductory epistle addressed ‘To the Great Variety of Readers’ they declare that the public has been ‘abused with divers stolen and surreptitious copies, maimed and deformed by the frauds and stealths of injurious impostors’. But now these plays are ‘offered to your view cured and perfect of their limbs, and all the rest absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them’.

None of the quartos believed by modern scholars to be unauthoritative was used unaltered as copy for the Folio. As men of the theatre, Heminges and Condell had access to theatre copies, and they made considerable use of them. For some plays, such as Titus Andronicus (which includes a whole scene not present in the quarto), and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the printers had a copy of a quarto (not necessarily the first) marked up with alterations made as the result of comparison with a theatre manuscript. For other plays (the first four to be printed in the Folio—The Tempest, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and Measure for Measure—along with The Winter’s Tale and probably Othello) they employed a professional scribe, Ralph Crane, to transcribe papers in the theatre’s possession. For others, such as Henry V and All’s Well That Ends Well, they seem to have had authorial papers; and for yet others, such as Macbeth, a theatre manuscript. We cannot always be sure of the copy used by the printers, and sometimes it may have been mixed: for Richard III they seem to have used pages of the third quarto mixed with pages of the sixth quarto combined with passages in manuscript; a copy of the third quarto of Richard II, a copy of the fifth quarto, and a theatre manuscript all contributed to the Folio text of that play; the annotated third quarto of Titus Andronicus was supplemented by the ‘fly’ scene (3.2) which Shakespeare appears to have added after the play was first composed. Dedicating the Folio to the brother Earls of Pembroke and Montgomery, Heminges and Condell claimed that, in collecting Shakespeare’s plays together, they had ‘done an office to the dead to procure his orphans guardians’ (that is, to provide noble patrons for the works he had left behind), ‘without ambition either of self profit or fame, only to keep the memory of so worthy a friend and fellow alive as was our Shakespeare’. Certainly they deserve our gratitude.