and lastly, Leocardia leaning on a burial mound:

Six of the fourteen Black Paintings which had been an enigma for centuries … Leon glanced at his notes, excitement rising. So it begins. The first painting, Deaf Man, was Goya himself. Goya had entered the Quinta del Sordo as an old, deaf man. The weird figure next to him, whispering into his deaf ear, was Death itself. He had come to the country house to die. But why? Leon looked at the next painting. Here began Goya’s testimony of his country, The Pilgrimage – a series of deranged people walking blindly in the semi-darkness. The Spanish people, driven insane by war and brutality, no longer human, walking into the abyss.

Then he turned to the third painting – Judith and Holofernes. Throughout art history it had represented the story of the Jewish queen who had seduced and then decapitated her lover and conqueror. But Leon knew this was no historical reference – Goya had not been depicting Judith, but Leocardia, his lover at the Quinta del Sordo … Excitement building, he scribbled down his thoughts, his hands moving rapidly. It was as though something had unlocked his brain and body; as though he had an open channel through which the information was pouring.

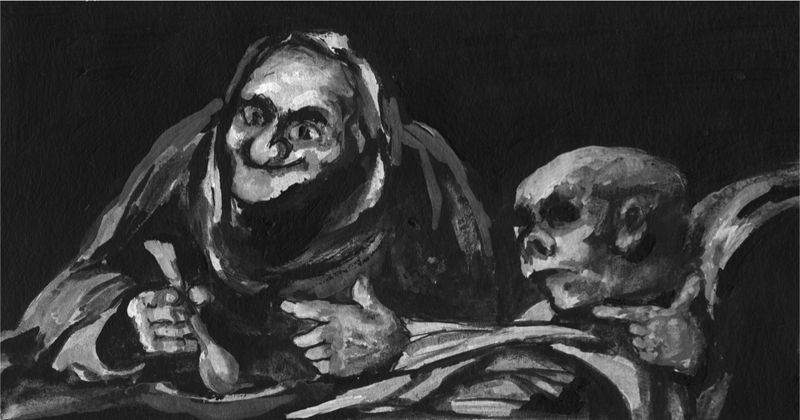

God, if only he had the skull! Leon thought desperately. What wouldn’t it tell him? What inspiration wouldn’t it magic on to the page? He thought of Gina and the medium, then Detita – and smiled to himself. His triumph was close. Close, breathable, touchable. If he kept working … His eyes moved on to another painting – the same queasy colours, background darkness swampy with malevolence. This time it was The Witchy Brew.

But now there was no Biblical prophet, only an aged female, grinning maniacally, and next to her the same half-human, half-dead figure, leaning – always leaning – towards what still lived.

Leon blinked as a searing thought occurred to him, then moved forward to study the right-hand figure. He stared into blank eyes, his heart rate speeding up as an idea came to him. Was that what Goya was painting? Swallowing, he tried to control his emotions as he looked back at the picture. Had the artist made dangerous enemies? Had he risked his own safety? Was it true what Detita had said so many years earlier – that Goya had been cursed, made ill and deafened deliberately, not by witches but by someone altogether more human?

Goya had become Court Painter and won the admiration of Spain, but he hadn’t kept it. What followed was his fall from grace, his questioning by the Inquisition, the Royals’ favourite out of favour because of their fall … Leon stared at the paintings intently, thinking of Goya. Who knew more about the caprices of fate? Who else had painted so much depravity and madness? The pictures were hardly finished – rough works, painted hurriedly as though the artist was in a frenzy.

Avidly, his gaze moved from one painting to another. He saw the Jewish queen cutting off her seducer’s head in Judith and Holofernes; he saw Saturn devouring the head of one of his own offspring, and the solitary, struggling dog, its head sticking above the quicksand, its body already sucked underneath into some gobbling, inescapable mass. So many decapitations, so many disembodied heads. Cut from their bodies. Stolen – just like Goya’s own.

Jesus! Leon thought desperately. Was the answer that obvious? He looked around, afraid that someone could overhear his thoughts. Was that the truth? he asked himself, his heart rate increasing, blood fizzing in his ears. Saturn … He knew! Christ! Leon thought. Was it that? Was this the evidence?

Was Goya – in that remote, secluded house – leaving a testimony behind? He was ill, old, beaten down by tragedy and cynicism. Did he dream of the Inquisition coming back to his door? Asking questions about him and Leocardia? Reeling, Leon leaned back in his seat, putting some distance between himself and the illustrations. He could suddenly picture the deaf world Goya lived in. A candle-lit, silent place, hermetically closed, the old man casting his long shadow on the walls.

He rubbed his temples. He was too tired to work but too tired to stop. He had to write it down – and then hide it. Along with the skull he would secrete the riddle of the Black Paintings. He would write it down, spell it out. On paper it would serve as a testament. And perhaps, once written down, it would loosen its grip.

In his excitement a cry escaped his lips. Sweating, he found himself light-headed, a queasy giddiness about to overwhelm him. Bartolomé Ortega would be so jealous … Leon laughed to himself, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand. All the Ortega money wouldn’t be enough. In the end it would come down to insight – Leon’s insight. The solving of the Black Paintings was simple for him. After all, it was only one madman talking to another.

One madman talking to another … Leon repeated the words in his head, disturbed by the thought. Getting to his feet he felt the room shift around him and knew he had pushed himself too far and gambled with his stability. Staggering to the door, he clasped the handle. He would go for a walk – get out of the house, away from the reproductions which were calling out to him from the desk.

But no longer from the desk.

Now they were all around him. Panicked, Leon turned, staring frantically at the hallucinations which filled the room. Witches were turning into goats, men’s faces were grinning without eyes and whispering without voices. He could hear the paintings talking, whispering, making catcalls in the dimness, as behind him the sound of unfolding wings beat like thunder against his skin.

His heart was pumping in his ears, his mouth open, gasping for air. The paintings vibrated in front of him, first becoming larger, swelling towards him, then retracting into murky black slivers of pure malice. And then he saw the painting of La Leocadia, Goya’s mistress, dressed in widow’s black, leaning on the huge dark mound of the artist’s grave. But as Leon looked, the paint peeled away and under the earth was not Goya, but himself. Still alive but deaf, blind and mute, clawing under the weight of earth. And the mourner wasn’t Leocadia but Detita, pressing Leon further and further into the suffocating earth.

In uncovering the secret of The Black Paintings Leon Golding had gone too far. Not only was he risking his sanity, but his life.

18

New York

Roberta Feldenchrist got out of the car, her chauffeur holding the door open for her. The warm air felt oily as she moved into the air-conditioned lobby of the apartment block. All her life Roberta – known to everyone as Bobbie – had lived on Park Avenue. All her life she had been surrounded by money, and when her parents divorced she stayed on with her father in the penthouse apartment, although the family actually owned three floors of the block. Her mother remarried but they had little in common and Bobbie rarely visited in France, even after Harwood Feldenchrist died.

Being an only child, it was not surprising that Bobbie inherited the Feldenchrist fortune and had full control. She left the property and banking interests to the board of directors her father had set up, but the running of the Feldenchrist art collection was entrusted to her. A lifelong chauvinist, Harwood had made it clear that although Bobbie wasn’t a boy, she had been as near a son as he would ever get. She had often wondered if that was why her father shortened her name to Bobbie.

Walking into the apartment she paused, glanced at her mail and then moved into the drawing room overlooking the park and the view beyond. The view spoke of privilege. Here she was above the streets, up with the gods – spoiled, preserved, chosen. Just like the paintings on the walls which surrounded her. The picture closest to her was Fragonard. Her father had loved French art and so had she, only later being introduced to the Spaniards and finally revelling in Goya. Something about the darkness had appealed to her, the bullfights and carnivals showing a side of life that was cruel as well as celebratory.