‘Hang on,’ Ben interrupted him. ‘So you don’t make the reconstruction over the skull itself?’

‘Never. You make a copy of the original skull, then use the copy for the reconstruction. That way you can poke about the replica without doing damage to the original.’

‘Go on.’

‘First you work out the landmark sights.’

‘Which means?’

‘The tissue and muscle depths,’ Francis replied, shrugging, delighted to have an audience. ‘Going on the shape of the skull, this man was a Caucasian, so from that I can work out the angle of the planes of the face.’

‘Then what?’

‘Then I gradually work out the outline of the bones, add muscle tissue, and try to reconstruct the forehead angle and the eyes. Of course the tip of the nose, the ears, eye and hair colour are always guesswork. We can only ever be sure of the bones we have, not the colouring or the skin texture of the subject.’

Patiently, Ben folded his arms. ‘What about the Madrid skull?’

‘Quite straightforward. Of course the age of the head had to be taken into consideration. And the fact that there were some parts of the skull missing.’

‘I saw that,’ Ben agreed. ‘A few rough holes. You know what caused them?’

‘Could be just wear and tear—’

‘Were they peri- or post-mortem?’

‘Post.’

‘Could they be a result of violence?’

‘Like what?’

‘Blows to the head?’

‘Doubt it. They were jagged. Uneven. Looks more like burial damage, animal attack.’ Francis shrugged. ‘I’ve done a lot of reconstructions for archaeologists and I’ve seen damage like this before on old skulls.’

‘What about getting the pathologist to look at it?’

‘I’ve already done that and he didn’t know much more than I did. Although he did say that the marks could have been caused by rubbing or by persistent scuffing.’ Francis paused. ‘Which sounded macabre – until I remembered that case about the kids in Liverpool using a skull as a football. When they found it it was filthy and they couldn’t make out what it was – just this grubby round object, so they kicked it around for a while. Boys will be boys!’

‘Especially in Liverpool.’

Putting on his glasses, Francis picked up some papers next to him, reading aloud. ‘The results have come through for the isotope and carbon dating. Having discovered what our man ate, it is consistent with Spanish grains from around the Madrid area, and the carbon dating puts him bang smack in the middle of your time period.’

‘So?’

‘Dates are accurate. Looks good so far.’

Unable to suppress his enthusiasm any longer, Francis snatched the cloth off the reconstructed Madrid head. Caught in full daylight, it seemed eerily realistic, the glass eyes gazing darkly into the laboratory, the chin flaccid, the outline of the cheeks slightly concave to represent the fact that they would have dropped a little with age. But the high forehead, the heavy mouth and the eye shape were disturbingly familiar.

A shiver of recognition, followed by unease, slid down Ben’s spine. He knew this man almost as well as a member of his own family. A face which had gazed out of books and down from cheap calendars throughout his childhood. A face that belonged to the man Detita had talked of repeatedly, slipping him into the brothers’ early life, into that hazy Spanish heat of their youth.

It was, without doubt, the face of the Goldings’ long-dead neighbour in Spain. Francisco Goya.

‘Jesus …’

‘So,’ Francis prompted him. ‘What d’you think?’

Staring at the reconstruction, Ben hesitated. And felt – for an instant – not triumph for his brother, but fear.

‘So,’ Francis repeated. ‘What d’you think?’

‘I think we’re looking at an old man. An old man who was arguably the greatest painter Spain ever produced.’

17

Madrid

The heatwave had finally broken, a storm marking the end of the freak weather, persistent rain making the weathercock rotate madly over the decrepit stables of the Madrid house. Inside, Leon drew the curtains and locked the windows, rechecking the back and front doors. He hadn’t shaved and his clothes smelled of stale sweat as he moved back into his study. After his last visit to the Prado he had avoided the gallery, even been tempted to go back on his medication. But gradually his panic subsided. How could he stop when the answer was finally in his hands? All he had to do now was to write his theory up, put it down on paper, then – when it was completed – turn it over to the world.

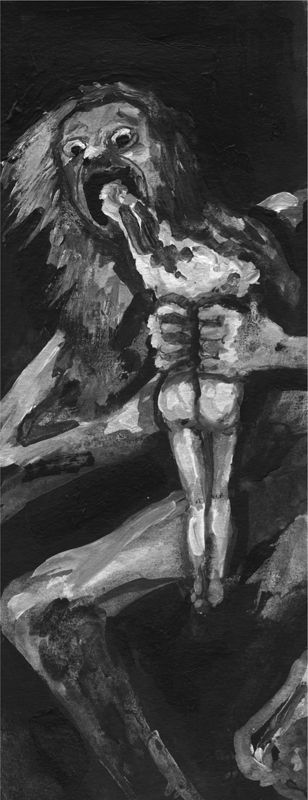

He knew how the art world worked. How critics, writers and collectors all vied for the top slot. Men searched for decades to uncover something unknown, some detail previously unexplained, some nuance gone unnoticed. But the Black Paintings were in another league. No one had ever known their true meaning. Theories mushroomed but dwindled into supposition. A hundred explanations had been offered, but never proved, never fulfilling the hunger for the truth about the most macabre pictures ever painted.

So it followed that the man who solved the enigma would become famous. The man who cracked the cipher would be the envy of the art world. He would become an authority no one could question. Respected, revered, admired.

Locking the door of his study, Leon checked his mobile, hearing the messages from Ben. For a moment he was tempted to call his brother, but found himself uncertain, chewing at the side of his index fingernail. The piece of paper Jimmy Shaw had given him had no name written on it, just a mobile number. Tucking the edge of the note under his desk lamp so that he could read the digits without needing to touch it, Leon wiped his hands.

To his surprise he felt sympathy for the man. Obviously dying, Shaw had managed to elicit some compassion in Leon – and an unwelcome guilt. But it was his skull! Leon thought desperately. No one else’s. And now everyone was after it. And after him. People had no right to be following him, questioning him. As for Gabino Ortega – what made him think he could demand details? He had been impertinently high-handed, almost imperious, although he was little more than a thug, challenging Leon outside the Prado. On his turf, talking to him as though he was a lackey!

Of course he had lied! What else could he do? Leon asked himself. He was hardly going to admit that he had Goya’s skull … Slumping into his seat, Leon felt an overwhelming desire to kick out. All his life he had longed for an opportunity to dazzle everyone. To finally put to rest the rumours about his mental instability. No one could deny him respect when he had the Goya skull. That, together with his explanation of the Black Paintings, would silence everyone.

Calming himself, he reached for his papers and began to read. A buzzing sounded in his ears as he read about Goya’s first major illness. About how the artist had been temporarily paralysed, his head full of noises. Normal speech and communication over … Sighing, Leon leaned back in his chair, placing the cut-outs he had made of each painting in the order in which they had been hung in the Quinta del Sordo. Soon he had the complete floor plans – upstairs and downstairs – in front of him, reading the paintings in the order they had been viewed.

Ground floor – Deaf Man, with the dead man talking to him:

The Pilgrimage:

Judith and Holofernes, the woman killing her rival:

Saturn eating one his children:

The Witches’ Sabbath: