After a severe bout of infirmity in winter 1116–17, Baldwin spent months convalescing, but by the start of 1118 he was ready to contemplate new military endeavours. That March he mounted an ambitious raiding campaign into Egypt, reaching the eastern branches of the Nile. In the midst of success, he suddenly fell desperately ill; the old wound received in 1103, from which he had never fully recovered, had now reopened. Deep in enemy territory, the great king found himself in such terrible pain that he was unable to ride a horse, and so, borne upon an improvised litter, he began a tortured journey back towards Palestine. A few days later, on 2 April 1118, he reached the tiny frontier settlement of al-Arish, but could go no further and there, having confessed his sins, he died.

The king had been determined that his body not be left in Egypt and so, after his death, his careful, if rather gruesome, instructions to his cook Addo were precisely followed in order to prevent his corpse rotting in the heat.

Just as he had resolutely asked, his belly was cut [open], his internal organs were taken out and buried, his body was salted inside and out, in the eyes, mouth, nostrils and ears [and] also embalmed with spices and balsam, then it was sewn into a hide and wrapped in carpets, placed on horseback and firmly tied on.

The funeral party bearing his remains reached Jerusalem that Palm Sunday and, in accordance with his last wishes, King Baldwin I was buried in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, beside his brother Godfrey of Bouillon.74

Although the First Crusaders prosecuted the initial invasion of the Levant, the real task of conquering the Near East and creating the crusader states was carried out by the first generation of settlers in Outremer. Of these, the greatest individual contributions were undoubtedly made by King Baldwin I and his rival Tancred of Antioch. Together these two rulers steered the Latin East through a period of extreme fragility, during which the myth of Frankish invincibility in battle cracked and the first intermittent signs of a Muslim counter-offensive surfaced. Between 1100 and 1118, perhaps even more than during the First Crusade, the real significance of Islamic disunity became clear, for in these years of foundation the western European settlement of Syria and Palestine quite probably could have been halted by committed and concerted Muslim attack.

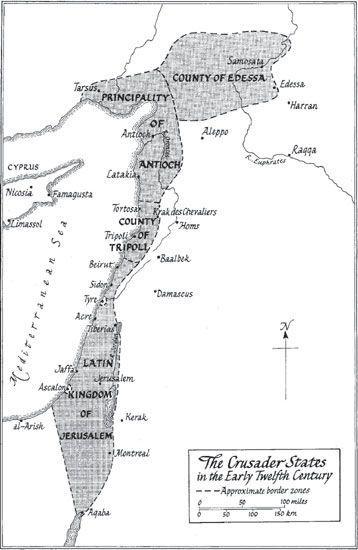

The Crusader States in the Early Twelfth Century

Baldwin’s and Tancred’s successes were built upon a flexibility of approach that mixed ruthlessness with pragmatism. Thus the work of consolidation and subjugation was carried out not simply through direct military conquest, but also via diplomacy, financial exploitation and the incorporation of the indigenous non-Latin population within the fabric of the Frankish states. Latin survival likewise was dependent upon the willingness of Baldwin, Tancred and their contemporaries to temper internecine competition and confrontation with cooperation in the face of external threats. There were some echoes of ‘crusading’ ideology in the struggle to defend the Holy Land, not least in the use of ritual purification before battle and the rise of the cult of the True Cross. But at the same time, early Latin settlers demonstrated a clear willingness to integrate into the world of the Near East, pursuing trading pacts, limited-term truces and even cooperative military alliances with their Muslim neighbours. Of course, this variety of approach simply mirrored and extended the reality of holy war witnessed during the First Crusade. The Franks continued to be capable of personifying Muslims, and even Greeks, as avowed enemies, while at a broader level still interacting with the indigenous peoples of the Levant according to the normalised customs of Frankish society.

5

OUTREMER

Just before first light on 28 June 1119 Prince Roger of Antioch gathered his army in readiness for battle. His men huddled together to listen to a sermon, partake of mass and venerate the Antiochene relic of the True Cross–girding their souls for the fight ahead. In the days leading up to this moment, Roger had reacted with decisive resolution to news of an impending Muslim invasion. After years of passively enduring Antiochene expansionism and repeated demands for exorbitant tribute, Aleppo had suddenly moved on to the offensive. Mustering a force–perhaps in excess of 10,000 men–the city’s new emir, the Artuqid Turk Il-ghazi, marched on the border zone with Frankish Antioch. Facing this threat, Roger could have waited for reinforcements from his Latin neighbours, including Baldwin of Bourcq (who had assumed the Jerusalemite crown in 1118). Instead, the prince assembled around 700 knights, 3,000 infantry and a corps of Turcopoles (Christianised mercenaries of Turkish birth) and crossed to the eastern flanks of the Belus Hills. Roger camped in a valley near the small settlement of Sarmada–which he believed was well defended by enclosing rocky hills–and that morning was about to initiate a swift advance, hoping to catch his enemy unawares and replay his success of 1115. Unbeknownst to the prince, however, on the preceding evening scouts had revealed the Christians’ position to Il-ghazi. Drawing upon local knowledge of the surrounding terrain, the Artuqid commander dispatched troops to approach Roger’s camp from three different directions and, as one Arabic chronicler attested, ‘as dawn broke [the Franks] saw the Muslim standards advancing to surround them completely’.75

THE FIELD OF BLOOD

With bugles sounding an urgent call to arms through the ranks, Roger rushed to organise his forces for combat, a cleric bearing the True Cross beside him. As Il-ghazi’s men closed in, there was just time to assemble the Latin host beyond the confines of the camp. In the vain hope of regaining the initiative, Roger ordered the Frankish knights on his right flank to deliver a crushing heavy charge and, at first, they appeared to have stemmed the Aleppan advance. But as battle was joined along the line, a contingent of Turcopoles stationed on the left wing buckled, and their rout splintered the Latin formation. Outnumbered and encircled, the Antiochenes were gradually overrun.

Caught at the heart of the maelstrom, Prince Roger was left horribly exposed, but ‘though his men lay cut down and dead on all sides…he never retreated, nor looked back’. One Latin eyewitness described how, ‘fighting energetically…[the prince] was struck by a [Muslim] sword through the middle of his nose right into his brain, and settling his debt to death [beneath] the Holy Cross he gave up his body to the earth and his soul to heaven’. The unfortunate priest carrying the True Cross was likewise cut down, although it was later said that the relic exacted its own miraculous revenge for this killing, causing all the Muslims nearby to suddenly become ‘possessed by greed’ for its ‘gold and precious stones’ and thus to begin butchering one another.

As resistance collapsed, a few Franks escaped westwards into the Belus Hills, but most were slaughtered. A Muslim living in Damascus described it as ‘one of [Islam’s] finest victories’, noting that, strewn across the battleground, the enemy’s slain horses resembled hedgehogs ‘because of the quantity of arrows sticking into them’. So terrible was this defeat, so great the number of Christian dead, that the Antiochenes thereafter dubbed the site ‘Ager Sanguinis’, the Field of Blood.