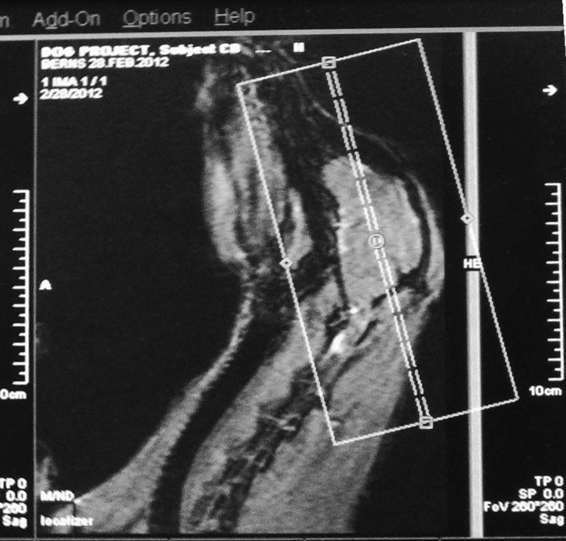

Callie’s localizer with box indicating field of view.

(Gregory Berns)

I nodded to Andrew. The buzzing continued. And then it stopped.

“What happened?” I asked. Andrew shrugged. Callie followed me into the control room. “Why did you stop the scan?”

Robert looked confused. “We didn’t,” he said. “Look.”

There, on the computer screen, was a perfect image of Callie in profile. The image was sliced right down the middle of her head, giving a beautiful view of her brain and spinal cord. Robert had already placed the bounding box for the field of view in place. The use of the recording through the intercom had worked so well that neither Callie nor I had noticed when the real scan started!

With the field of view set, we cued up the functional runs. I showed Callie the container of hot dogs, and her eyes widened. All I had to do was point to the magnet, and she scooted in.

This time, we played the recordings from the functional sequence through the intercom. The volume was gradually increased, and after a few seconds, I could hear the real scans begin. They sounded almost identical. Callie didn’t care. Her eyes were lasers on mine. I held up my left hand to indicate that she had done well and gave her a piece of hot dog.

We were off and running. I alternated repetitions for hot dogs and no hot dogs but kept it somewhat unpredictable, throwing in runs of two or three of the same trial type. Callie stayed cool as a cucumber. Every time I put up the sign for “no hot dog,” she stared at me and waited until I put up the sign for “hot dog.” I began to appreciate that rather than being disappointed during the no hot dog trials, Callie viewed those hand signals as uninformative. Being told that she wouldn’t get a hot dog said nothing about when she would get one. This interpretation would soon be borne out by her brain activation.

Unlike the previous scan session, this time we were much more efficient. In short order, we had acquired two five-minute runs of functional scans, nearly four hundred images in total. The only thing that remained was the thirty-second structural scan. At this point, Callie looked either tired or bored, but in she went for the fourth time. The recordings of the structural sequence were slowly ramped up through the intercom, and then the real scan started. The structural sequence sounds much like the localizer, but Callie stayed put throughout.

She had done it. She hadn’t moved at all. I ran around the scanner and gave her a handful of hot dog.

“You are such a good girl!” I exclaimed. “You are a SuperFeist!”

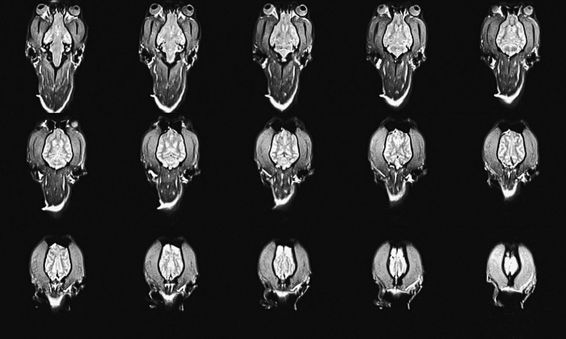

Robert already had the structurals on the screen. There, in breathtaking clarity, was the first detailed structural image of a completely awake dog. My jaw dropped. We had just acquired nearly four hundred functional scans and a structural image that rivaled anything we got in humans.

The first detailed structural image of Callie’s brain rivals the quality of human scans.

(Gregory Berns)

Even if McKenzie bombed on her turn, I was confident that we had achieved our goal of getting enough functional scans.

“How many repetitions did we get?”

“It looks like she did twenty trials with hot dog and nineteen trials of no hot dog,” Andrew said.

“Damn,” I marveled. “That should be plenty for analysis. Let’s hope the SNR is high enough.”

Callie sat down next to me. I looked into her eyes, and she knew. Yeah, I’m the top dog.

If I’d had any lingering concerns about Melissa and McKenzie, those quickly disappeared. The trick of playing the recordings through the intercom worked wonders for them too. We finally got a localizer image for McKenzie, which allowed us to precisely place the field of view to avoid chopping off half her brain this time. For the functional scans, Melissa was more collected than I had been. She really took her time with the repetitions, requiring McKenzie to hold still for fifteen seconds for each trial, where I had required Callie to hold still for only ten.

McKenzie was like a rock. Robert and I watched her images stream on the console in real time. She was not moving. Not at all. They blazed through the two functional runs, and, for the first time, we got a structural image of McKenzie’s brain.

Two for two.

Not only was the day a complete success, but we had accomplished all of this in two hours—half the time of the previous session.

It was still exhausting. When you’re locked face-to-face inside the magnet with jackhammers all around you, the level of concentration, for both dogs and humans, is intense. When Callie and I finally got home, we crashed together on the couch. We looked at each other once and then closed our eyes.

19

Eureka!

ANDREW DIDN’T WASTE ANY TIME. The next day, he had already begun the analysis of Callie’s and McKenzie’s data. Just like the peas and hot dogs experiment, the first and trickiest part of the analysis would be the motion correction. We had to carefully identify which scans contained brains and discard the ones in which the dogs moved too much. Animating the sequence of images in rapid speed helped make the task easier.

Andrew showed me the animation.

“Check this out,” he said. A pixelated image of a dog’s brain danced on the computer screen. For stretches of several frames, which were actually tens of seconds in real time, the image didn’t move. Except the eyeballs, which darted left and right.

“This is Callie,” Andrew continued. “She did really well. If we throw out the scans with movement artifacts, we still have 62 percent left for analysis.” My heart swelled in pride at my beloved feist.

“That’s amazing,” I said. “That is five times better than the previous session. How about McKenzie?”

“Almost as good. We can keep 58 percent. She had sixteen hot dog trials and eleven no hot dog trials.”

“Melissa was really making her hold still for a long time,” I said.

“Yes,” Andrew said, “but that means we’ll have a lot of scans for each repetition.”

We spent the next two days checking and rechecking each step of the analysis. To make sure that we didn’t mistakenly confuse brain activation with movement artifacts, we kept ratcheting up our criteria for whether to keep a scan in the analysis. Andrew and I would stare at the animations, looking for even the slightest twitch of the head. Most of the head motion occurred when we gave the dogs hot dogs. This was no surprise. But we weren’t interested in the brain response to hot dogs. We were interested in the response to the hand signals. When we were satisfied that we had identified and discarded all the scans with motion, the remaining scans showed that the dogs had held their heads with less than one millimeter of movement during the critical period of the hand signals. That was as good as humans do in the scanner. We were ready for the final step: comparing the activation between the two hand signals.

All fMRI experiments measure relative changes in brain activity between different conditions. With only two conditions—the signal for “hot dog” and the signal for “no hot dog”—all we had to do was subtract the brain activity in one condition from the other. The difference would show us which parts of the dogs’ brains processed the meaning of the signals.