Helen had been eagerly waiting for Dog Day too. She had made an earnest attempt to improve her study habits, making flash cards and going through them diligently. The night before scan day, I kissed her good night.

“Dad,” she asked, “am I going with you to work tomorrow?”

“Yes,” I said. “I’m very proud of how hard you’ve been working. I know science is a hard class. Tomorrow you’ll see how much fun science can be.”

She smiled and gave me a hug.

There was no sleep for me that night. I lay in bed wide awake. Callie was curled up between Kat and me. I rested a hand on Callie’s smooth fur and immediately felt the calming effect of her chest rising up and down slowly. Newton had had the same calming effect, augmented by his soft snoring.

With nothing to do but let my imagination spin away, Edward Jenner popped into my head. In 1796, Jenner invented the smallpox vaccine. He had made the astute observation that women who milked cows were immune to smallpox. Jenner suspected that the blisters the milkmaids acquired from a similar disease, cowpox, contained a substance that could provide immunity to other people. Jenner tested his theory on James Phipps, the eight-year-old son of his gardener. After inoculating James with pus from a milkmaid, Jenner exposed him to the real smallpox virus. James didn’t get sick. Thanks to Jenner, the world is now rid of smallpox.

What Jenner did, though, could never be done today. He took an outrageous risk. If he had been wrong, the boy would have contracted smallpox and would probably have died. Perhaps the gardener had no choice in the matter, but I still admire Jenner for having the courage to test his theory on a member of his own household. If today’s biomedical researchers were required to test their theories first on people they know, there would be a lot less crap making it into the scientific archives.

Callie was a part of our family. And I was about to pull a Jenner on her. I had no qualms about going into the MRI myself. I routinely volunteered for the lab’s experiments. But Callie wasn’t human. There was much we didn’t know about dogs. Mark had told me stories about dogs that had found their way home after being lost hundreds of miles away. How did they do that? Maybe they were like pigeons and had some primitive magnetic sense in their brains. Would the MRI blind Callie’s sense of direction?

We were about to venture into unknown territory. People would question what we were doing. Some might view this as animal torture, even though we had elevated the dogs’ rights to those of humans.

There was no other way. It had to be family.

15

Dog Day Afternoon

THE NEXT MORNING, HELEN HELPED me load up the car. I couldn’t tell if she was more excited about seeing the experiment or playing hooky from school. It didn’t matter. It was great to have her along.

I’d prepared a checklist to make sure we didn’t forget anything: earmuffs, chin rest, hot dogs, peas, nylon collars and leashes with the metal removed to be MRI-safe, and plastic steps. We tried to be discreet about it, but as soon as Callie saw the chin rest, she started pogo-sticking in excitement. She followed us to the garage door and wiggled between my legs to run to the car.

The three of us arrived at the lab just before noon, and it was already packed. Since this might never happen again, we also had a photographer come to document everything. To make sure we were in compliance with the IACUC protocol and to look out for the welfare of the dogs, we had requested a veterinary technician. I had no idea who would be sent and what he or she would think about the Dog Project, but any concerns I’d had instantly disappeared when Rebeccah Hunter introduced herself. Rebeccah was young and enthusiastic and, most important, a dog person. Callie ran over to her and jumped up to lick her face. As any dog person knows, this is a crucial test in evaluating someone’s character. Do they back away in disgust or do they lean into the doggie kiss?

Rebeccah being greeted by McKenzie.

(Bryan Meltz)

Rebeccah not only leaned in, she knelt down to Callie’s level and cooed, “Oh, what a good girl!” Callie planted one right on her lips.

I didn’t know it yet, but Rebeccah’s rapport with the dogs would be crucial in just a few hours.

Mark and Melissa soon arrived with McKenzie, and we let the dogs run around the lab to burn off nervous energy. They zoomed from person to person, making sure everyone got a good sniffing. Callie’s tail never stopped wagging. Even when lying on the floor, her tail would begin thwack-thwacking whenever someone approached her. After ten minutes of playtime, both dogs had settled down. For what was about to happen, we wanted the dogs as calm as possible. Being a little tired would help them hold still in the MRI.

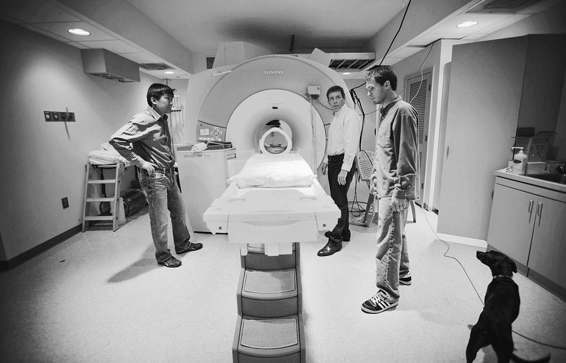

Sinyeob, I, Andrew, and Callie ponder the MRI.

(Bryan Meltz)

We swapped the dogs’ collars for nylon ones. I had replaced the standard metal D-rings and clips on these leashes with plastic equivalents. Everyone did a double-check for metal in their pockets, like keys and cell phones, and for credit cards that would be erased if they got too close to the magnet. Normally, we would do the metal check in the control room at the scanner, but in order to avoid parading the dogs through the halls of the hospital, we would be entering the MRI room directly from outside through a side door. We needed to make sure everyone who was going to be in the room was MRI-safe.

At the scanner, we were greeted by Robert Smith, the tech who would run the MRI and who had been there for Callie’s dress rehearsal, and Sinyeob Ahn, a magnetic resonance physicist from China who would tweak scanner settings for us on the fly. They both smiled when they saw Callie and McKenzie, but I could tell neither of them thought this would actually work.

I heaved shut the vaultlike doors to the magnet room, creating a seal impenetrable by any form of electricity or radio waves. With the room secured and the doors locked, we let the dogs off-leash. Callie, of course, had been here before and knew that crumbs of food could be found on the floor of the control room. She gave only a passing glance at the magnet as she went off in search of something to eat. McKenzie gave the MRI her best border collie stare. Despite the susurrations of the cryogen pump, McKenzie soon realized that the magnet was not alive and could not be herded.

While Melissa worked with McKenzie to get comfortable around the magnet, I settled in with Robert and Sinyeob to plan the afternoon’s scans. Based on what we had learned from Callie’s dress rehearsal, we would implement several changes in the scan protocol.

From the control room I could see Melissa coaxing McKenzie into the scanner. Tentative at first, McKenzie carefully walked up the steps and plopped down on the patient table. She seemed unsure of what to do. Melissa went around to the other end of the magnet and, using some hot dogs, lured McKenzie in. As soon as Callie caught sight of that, she ran up the steps and climbed over McKenzie to stake out her position inside the magnet.