CHAPTER 1

From Cairo to Istanbul

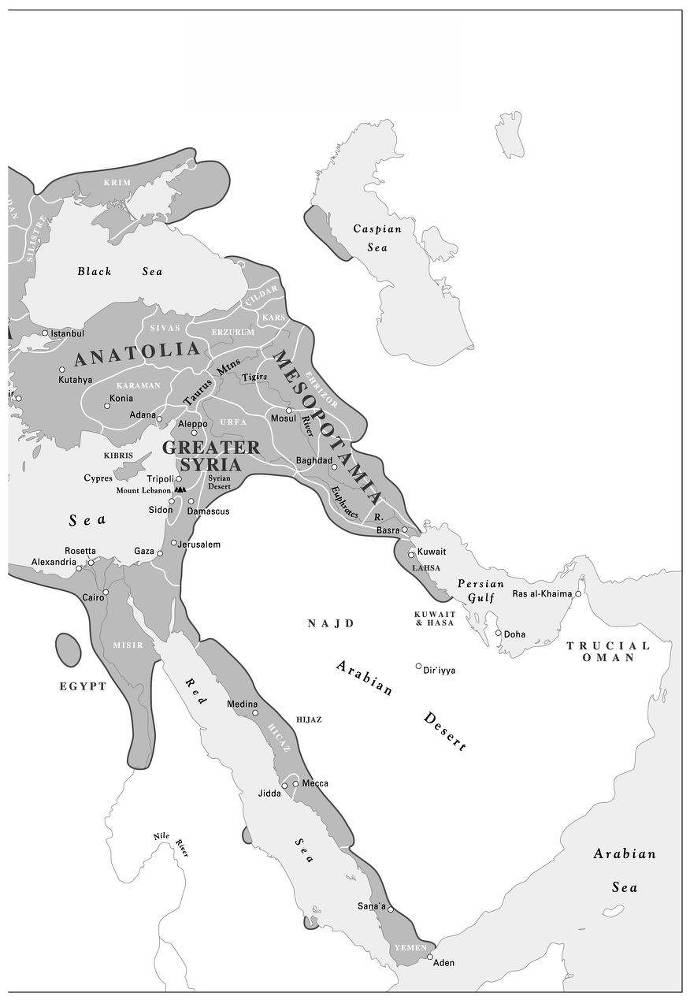

The hot summer sun beat down upon al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri, forty-ninth sultan of the Mamluk dynasty, as he reviewed his troops for battle. Since the founding of the dynasty in 1250, the Mamluks had ruled over the oldest and most powerful Islamic state of its day. The Cairo-based empire spanned Egypt, Syria, and Arabia. Qansuh, a man in his seventies, had ruled the empire for fifteen years. He was now in Marj Dabiq, a field outside the Syrian city of Aleppo, at the northernmost limits of his empire, to confront the greatest danger the Mamluks had ever faced. He would fail, and his failure would set in motion the demise of his empire, paving the way for the conquest of the Arab lands by the Ottoman Turks. The date was August 24, 1516. Qansuh wore a light turban to protect his head from the burning sun of the Syrian desert. He wore a regal blue mantle over his shoulders, on which he rested a battle axe, as he rode his Arabian charger to review his forces. When a Mamluk sultan went to war, he personally led the troops in battle and took most of his government with him. It was as if an American president took half his cabinet, leaders of both houses of Congress, Supreme Court justices, and a synod of bishops and rabbis, all dressed for battle alongside the officers and soldiers. The commanders of the Mamluk army and the four chief justices stood beneath the sultan’s red banner. To their right stood the spiritual head of the empire, the caliph al-Mutawakkil III, under his own banner. He too was dressed in a light turban and mantle, with a battle axe resting on his shoulder. Qansuh was surrounded by forty descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, who wore copies of the Qur’an enveloped in yellow silk cases wrapped around their heads. The descendents were joined by the leaders of the mystical Sufi orders under green, red, and black banners.

THE ARAB WORLD IN THE OTTOMAN ERA, 1516-1830

Qansuh and his retinue would have been impressed and reassured by the spectacle of 20,000 Mamluk soldiers massed in the plains around them. The Mamluks—the word in Arabic means “one possessed” or “slave”—were a caste of elite slave soldiers. Young men were brought from Christian lands in the Eurasian steppe and the Caucasus to Cairo, where they were converted to Islam and trained in the martial arts. Separated from their families and homelands, they owed their total loyalty to their masters—both those who physically owned them and those who taught them. Trained to the highest standard in warfare and indoctrinated into total devotion to religion and state, the mature Mamluk was then given his freedom and entered the ranks of the ruling elite. They were the ultimate warriors in hand-to-hand combat and had overpowered the greatest armies of the Middle Ages: in 1249 the Mamluks defeated the Crusader army of the French king Louis IX, in 1260 they drove the Mongol hordes out of Arab lands, and in 1291 they expelled the last of the Crusaders from Islamic lands. The Mamluk army was a magnificent sight. Its warriors wore silk robes of brilliant colors, their helmets and armor were of the highest craftsmanship, and their weapons were made of hardened steel inlaid with gold. The show of finery was part of an ethos of chivalry and a mark of confidence of men who expected to carry the day. Facing the Mamluks across the battlefield were the seasoned veterans of the Ottoman sultan. The Ottoman Empire had emerged at the end of the thirteenth century as a minor Turkish Muslim principality engaged in holy war against the Christian Byzantine Empire in Anatolia (the Asian lands of modern Turkey). Over the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Ottomans had integrated the other Turkish principalities and conquered Byzantine territory in both Anatolia and the Balkans. In 1453 the seventh Ottoman sultan, Mehmed II, succeeded where all previous Muslim attempts had failed when he seized Constantinople and completed the conquest of the Byzantine Empire. Henceforth Mehmed II would be known as “the Conqueror.” Constantinople, renamed Istanbul, became the Ottoman capital. Mehmed II’s successors proved no less ambitious in expanding the territorial reach of their empire. On this day in 1516, Qansuh was about to engage in battle with the ninth Ottoman sultan, Selim I (r. 1512–1520), nicknamed “the Grim.” Paradoxically, Qansuh had hoped to avoid going to war by making a show of strength on his northern frontier. The Ottomans were engaged in hostilities with the Persian Safavid Empire. Ruling in what is now modern Iran, the Safavids spoke Turkish like the Ottomans and were probably of Kurdish ethnic origins. Their charismatic leader, Shah Ismail (r. 1501–1524), had decreed Shiite Islam the official religion of his state, which put him on an ideological collision course with the Sunni Ottoman Empire.1 The Ottomans and Safavids had fought over Eastern Anatolia in 1514–1515, and the Ottomans had emerged victorious. The Safavids urgently sought an alliance with the Mamluks to contain the Ottoman threat. Qansuh had no particular sympathy for the Safavids, but he wanted to preserve the balance of power in the region and hoped that a strong Mamluk military presence in northern Syria would confine Ottoman ambitions to Anatolia, leaving Persia to the Safavids and the Arab world to the Mamluks. Instead, the Mamluk deployment posed a strategic threat to the Ottoman flank. Rather than run the risk of a two-front war, the Ottoman sultan suspended hostilities with the Safavids to deal with the Mamluks. The Mamluks fielded a great army, but the Ottoman force was greater by far. Its disciplined ranks of cavalry and infantry outnumbered the Mamluks by as much as three to one. Contemporary chroniclers estimated Selim’s army to number 60,000 men in all. The Ottomans also enjoyed a significant technological advantage over their adversaries. Whereas the Mamluks were an old-fashioned army that placed much emphasis on individual swordsmanship, the Ottomans fielded a modern gunpowder infantry armed with muskets. The Mamluks upheld medieval military values while the Ottomans represented the modern face of sixteenth-century warfare. Battle-hardened soldiers with extensive combat experience, the Ottomans were more interested in the spoils of victory than in gaining personal honor through hand-to-hand combat.

As the two armies engaged in battle at Marj Dabiq, Ottoman firearms decimated the ranks of the Mamluk knights. The Mamluk right wing crumbled under the Ottoman offensive, and the left wing took flight. The commander of the left wing was the governor of the city of Aleppo, a Mamluk named Khair Bey who, it transpired, had been in league with the Ottomans before the battle and had transferred his allegiance to Selim the Grim. Khair Bey’s treachery delivered victory to the Ottomans shortly after the start of battle. The Mamluk sultan, Qansuh al-Ghawri, watched in horror as his army collapsed around him. The dust on the battlefield was so thick that the two armies could hardly see each other. Qansuh turned to his religious advisors and urged them to pray for a victory he no longer believed his soldiers could deliver. One of the Mamluk commanders, recognizing the hopelessness of the situation, took down the sultan’s banner, folded it, and turned to Qansuh, saying: “Our master the Sultan, the Ottomans have defeated us. Save yourself and take refuge in Aleppo.” As the truth of his officer’s words sunk in, the sultan suffered a stroke that left him half paralyzed. When he tried to mount his horse, Qansuh fell and died on the spot. Abandoned by his fleeing retinue, the sultan’s body was never recovered. It was as though the earth had opened and swallowed the fallen Mamluk’s body whole. As the dust of battle settled, the full horror of the carnage became apparent. “It was a time to turn an infant’s hair white, and to melt iron in its fury,” the Mamluk chronicler Ibn Iyas reflected. The battlefield was littered with dead and dying men and horses whose groans were cut short by the victorious Ottomans in their eagerness to rob their fallen adversaries. They left behind ?headless bodies, and faces covered with dust and grown hideous? to be devoured by crows and wild dogs.2 It was an unprecedented defeat for the Mamluks, and a blow from which their empire would never recover.