Patton will later insist that he did not know Waters was incarcerated in Hammelburg. Yet the truth is he was informed of this fact by the American Military Mission in Moscow on February 9. Furthermore, on the eve of the attack, Patton specifically wrote to Beatrice, “Hope to send an expedition tomorrow to get John.”

Patton’s staff questioned his plan to rescue the prisoners, stating that Patton needed at least thirty-five hundred men to liberate the POW camp, rather than the mere three hundred who were being deployed. Even the hero of Bastogne, Lt. Col. Abe Abrams, thought the mission so foolish that he turned it down, giving the command role to Lt. Harold Cohen. But Cohen didn’t want it, either. He told Patton that he was incapacitated by hemorrhoids. Patton called Cohen’s bluff, ordering that he be taken into the next room and examined by a doctor. Only when the hemorrhoids were confirmed did Patton give the lead role to Capt. Abraham J. Baum, the twice-wounded twenty-three-year-old son of a Brooklyn blouse maker.

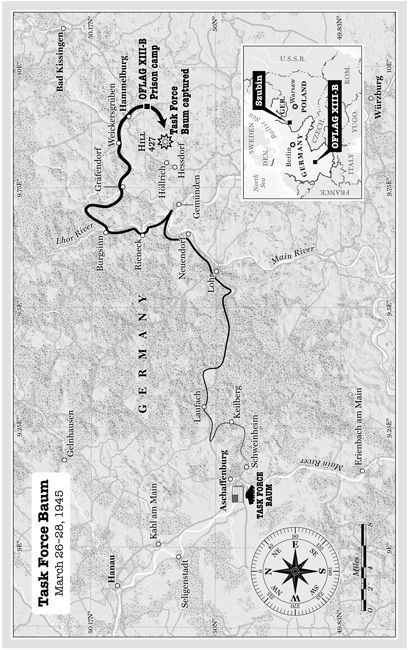

Baum and his rescue force were already exhausted from the Rhine crossing. They were handed just fifteen maps for fifty-seven vehicles. It was possible that Task Force Baum would not even find Hammelburg, let alone the POW camp.

Yet Patton, normally such a meticulous planner, ordered the rescue mission to proceed. Gen. Douglas MacArthur had received a great deal of media exposure for liberating thousands of Allied POWs in the Pacific, and Patton hoped to “make MacArthur look like a piker.”3

German opposition was heavy, and soon half the task force lay dead or dying.

But the Americans got through. Less than twenty-four hours after setting out, Task Force Baum miraculously arrived at the gates of Oflag XIII-B, as the camp was known. Seeing gray uniforms, they began firing at what they mistakenly believed to be German guards. Instead, the uniforms belonged to Serbian prisoners of war being interned at the camp. The German commandant, Gen. Günther von Goeckel, took pity on the Serbians and requested that a contingent of American prisoners march out the gates and tell their rescuers to cease firing. Meanwhile, von Goeckel and the remaining German guards fled. They no longer had any interest in defending the camp.

At 6:15 p.m., Patton’s son-in-law Colonel Waters marched out the front gate carrying a white flag of surrender. Several American officers and a lone German officer were by his side. Waters was noticeably gaunt from more than forty pounds of weight loss. He walked slowly, intending to tell Captain Baum to stop firing.

Waters never made it. A German guard in a camouflage uniform, not knowing that a truce had been arranged by the camp commandant, steadied his rifle atop a fence post and took careful aim. The bullet entered John Waters’s right hip and exited through his left buttocks. He collapsed to the ground, where he lay until he could be carried back into the camp. There, fellow POW and chief surgeon of the Yugoslavian Army, Radovan Danic, quickly removed the bullet.

As Task Force Baum stormed the gates to the camp, cheered by hundreds of American prisoners, one thing became quite clear: Col. John Waters wasn’t physically capable of going anywhere.

Captain Baum soon found himself faced with another dilemma: instead of three hundred POWs, there were well over a thousand. The task force simply didn’t have enough vehicles to carry every single prisoner back to freedom. The convoy needed to turn around and race back to the American lines under cover of darkness before the Germans could counterattack.

An estimated seven hundred prisoners soon draped themselves atop tanks and halftracks, gorging themselves on K-rations the task force had brought along for just that purpose.4 Those well enough to walk followed along behind the column.

The Germans counterattacked at sunrise the next morning. The strength of the Nazi reprisal was terrifying. Swiftly and efficiently, they destroyed the American column and began rounding up the POWs for their return to Oflag XIII-B. Many who were not prisoners of war before the rescue attempt now found themselves in German captivity. Wehrmacht soldiers used dogs to hunt down the Americans now scattered across the countryside. Captain Baum was burned when a rocket hit his tank, and suffered a gunshot wound to the groin, yet he managed to evade the Germans for almost twenty-four hours before being captured and led into captivity.5

Nine days later, the American Fourteenth Armored Division liberated the POW camp. Patton’s initial raid, which had cost thirty-two men their lives, was all for naught.

George Patton immediately visited his son-in-law at a hospital in Frankfurt, where Colonel Waters had been taken to recuperate from his wounds.

Upon seeing Patton, the colonel burst out, “Did you know I was at Hammelburg?”

It was the first question out of Waters’s mouth, because he well knew that many considered him to blame for a horrible waste of American lives. Thirty-two Americans had been killed, and almost three hundred more wounded or taken prisoner. In addition, sixteen tanks, twenty-eight halftracks, twelve jeeps, and a medical vehicle known as a Weasel were destroyed.

“Not for sure,” came the answer from his father-in-law.

* * *

Patton has sworn a professional oath of honor that does not allow lying, cheating, or tolerating those who do so. Covering up the real reason for Task Force Baum was not the first of George S. Patton’s untruths. One lie, in particular, broke his wife Beatrice’s heart and almost cost him his marriage, and may now be coming back to haunt him. For the beautiful young woman with whom he was secretly unfaithful has once again entered his life.

The year was 1935. The place was Hawaii. Jean Gordon was visiting the Patton family on her way to the Orient. A willowy unmarried young woman who spoke fluent French, she was the daughter of Beatrice Patton’s half sister, and thus the general’s niece by marriage. She also served as maid of honor at the wedding between Patton’s daughter Beatrice and John Waters. Patton was old enough to know better, a career soldier and the father of three children who had long enjoyed the love of a wife who understood his unusual temperament. Beatrice was a remarkable woman in her own right, capable of making conversation in German, French, Spanish, and Italian. She had written a book, and had a passion for music and drama. And her ferocious passion for her husband was such that, on one occasion, she physically attacked an officer who had disparaged her beloved Georgie. Patton had to pry her off the man when she knocked him down and was banging his head on the tile floor.

When the eighteen-year-old Jean began flirting with her husband, Beatrice was unaware. George Patton was flattered. So it was that when Beatrice Patton fell ill shortly before a planned journey from one Hawaiian island to another, Jean went in her place. There was no chaperone to prevent what occurred next.

Jean Gordon in her Red Cross uniform

When a heartbroken Beatrice learned of the tryst, she told her daughter Ruth Ellen, “It’s lucky for us that I don’t have a mother. Because if I did, I’d pack up and go home to her now.”

That might have been the end of it, because for all intents and purposes the relationship between George Patton and Jean Gordon seemed to have run its course.

But in the summer of 1944, Jean arrived in England as a Red Cross volunteer and wasted no time in reconnecting with Patton. When Beatrice learned that Jean was in England, she wrote to her husband that she was aware that Patton’s former lover had returned to his side, but Patton denied spending time with the young woman. Still, once the Third Army began its drive across France, Jean managed to get assigned to the task of Red Cross “donut girl” for the troops, visiting them and providing them with donuts, hot coffee, and conversation. She became a regular at Patton’s headquarters, where she often spoke fluent French with the general.