“The bearing of the British nation at that time of stress, when we were all alone, filled him and vast numbers of his countrymen with the warmest sentiments towards our people,” Churchill says to the members of Parliament.

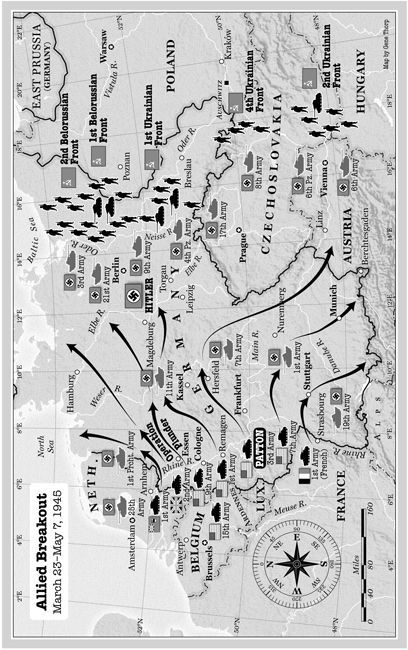

The same Roosevelt of whom Churchill now speaks so warmly is the very politician who has just given Berlin to the Russians. All Allied forces on the Western Front, Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery’s included, have been ordered to halt sixty miles short of Berlin, on the banks of the Elbe River.

The command came from Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, who now inexplicably sees Berlin as having no strategic value. Yet as Winston Churchill knows all too well, the order could not have been given without the approval of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. There are four million Allied soldiers in Germany right now, and three million of them are American. The people of the United States would find it unsettling to see a British commander get the glory of capturing the German capital, though Eisenhower sees no problem in allowing a Russian commander to know that very same sense of glory.

The British people will be denied that symbolic moment when Monty and his Tommies march into Berlin. There will be no victorious poses in front of Hitler’s bombed-out Reichstag, allowing all of England to rejoice that their plucky island nation persevered in the face of long odds, and finally conquered the Führer’s capital.

Making the betrayal sting even more is the fact that Churchill is half American. His mother, the beautiful Jenny Jerome Randolph, is from Brooklyn. His grandfather was editor of the New York Times. His ancestors came to America on the Mayflower, and a later generation wintered with George Washington at Valley Forge and waged a revolution against the British. Churchill is even distantly related to a Native American of the Iroquois nation. In this way, his forefathers were even more American than those of the late president.

Yet it is America that now commits the unconscionable act of deferring to Russia at the expense of Britain—in effect, killing England.

Winston Churchill is sad. Sad for his lost friend, sad for FDR’s betrayals, sad for his nation, and, in the end, sad for the uncertainty that is to come. Churchill has already exchanged a number of cables with Harry Truman, and has yet to get a clear read on him.

After so many years of being wary of Nazi Germany, Churchill now sees the Russians as the world’s greatest threat. The divide between the Communist worldview and that of Britain’s is so great that Churchill will compare it to an “iron curtain,” a phrase that will go down in history.

Churchill has been prime minister for five years. But unbeknownst to him, he will be voted out of office in just three months—rejected by the nation he loves, just as he was pushed aside by Stalin and FDR.

“For us, it remains only to say that in Franklin Roosevelt there died the greatest American friend we have ever known, and the greatest champion of freedom who has ever brought help and comfort from the new world to the old,” Churchill concludes to a chorus of “Hear, hear” from MPs on both sides of the aisle.

The exhausted prime minister has spoken for twenty minutes. He then takes his seat. Winston Churchill could use a scotch. This has been a very long day.

20

THIRD ARMY HEADQUARTERS

HERSFELD, GERMANY

APRIL 17, 1945

MORNING

George Patton and Winston Churchill are simpatico. They both believe that the Soviet Union is now the biggest threat to the world and to democracy. Patton is convinced that Churchill is the only man in power who knows what the world is “walking into.”

For now, Patton keeps his comments to himself. Volatile words could get him fired—or even killed. Patton is a man of strong beliefs, and as he will tell the press in a few weeks, he is utterly sure of the Russian danger: “Churchill had a sense of history. Unfortunately, some of our leaders were just damn fools who had no idea of Russian history. Hell, I doubt if they even knew [that] Russia, just less than a hundred years ago, owned Finland, sucked the blood out of Poland, and were using Siberia as a prison for their own people. How Stalin must have sneered when he got through with them at all those phony conferences.”1

This morning, Patton sits at his desk in one of the small trailers that form his mobile command center, thinking about his future. Unless he finagles a command in the Pacific, he knows that his career is all but done.

Still a powerful force, the Third Army was poised to wheel north to capture Berlin, just as they made the hard left turn for Bastogne until Eisenhower stopped them.

Patton believes that letting the Russians have Berlin is folly. And he told Eisenhower this a few days ago. Americans should not only take Berlin, Patton said, but keep on pushing as far to the east as possible. In time, the entire world will come to realize that he is right.

But by then it will be too late. The Russians have already pushed through Austria and are now approaching Fortress Berlin from the south and east. Soon they will take total control of Eastern Europe—a stranglehold they will maintain for the next fifty years.

Fear of the Russians is spreading throughout Germany. Millions of civilian refugees flee toward the American lines—only to be turned back.2 More than a half million German soldiers have raised their hands in surrender so that they will not have to face the Russians. In fact, so many Wehrmacht fighters are giving up that the Allies no longer accept all prisoners of war, because it is impossible to house and feed so many men. When the men of the once feared Eleventh Panzer Division attempt to quit the war, the Third Army will accept them as prisoners only under the condition that they bring their own food.

As Patton sips coffee in his headquarters, he knows that his future may lie as a civilian. He has once again appeared on the cover of Time magazine, and is at last getting the kind of public respect and glory he so desperately craves. Should Patton enter politics, he will be a formidable force.

But the war isn’t over. For the first time in recent memory, the Third Army is not being ordered to go on the defensive. In fact, the opposite is true. Patton has just been given an additional three armored divisions so he can spearhead the final American attacks of the war in southern Germany.

“There was a big meeting yesterday and we got the ball for what looks like the final play,” he writes to Beatrice. As a general, he is not subject to having his letters read by the military censors. Yet his wording is deft, nonetheless: he alludes to what is about to happen yet does not violate national security, lest this letter somehow fall into German hands.

His letter to his wife continues: “Sometimes I feel that I may be nearing the end of this life. I have liberated ‘J.’ and licked the Germans. So what else is there to do?”

The “J.” to whom Patton refers is his son-in-law, thirty-eight-year-old Col. John Waters, who was captured in Tunisia two years ago.

* * *

On the surface, Task Force Baum, the “Hammelburg mission,” was simply a daring attempt to rescue American prisoners of war. Shortly after crossing the Rhine in late March, Patton received word that the POW camp near the German town of Hammelburg held three hundred U.S. soldiers—many of them officers. Its location was sixty long miles from Patton’s army. Among them was Col. John Waters, the husband of Patton’s beloved daughter Beatrice.

After conquering the Polish town of Szubin, Russian soldiers had discovered the remains of a hastily abandoned POW camp. The Allied prisoners had been marched three hundred miles west in the dead of February to prevent their falling into Russian hands. Prison records showed that Waters was once incarcerated there.