Somehow Helena and Rozinka escape being raped. However, they must silently listen to the screams of those women being violated, and then the heart-wrenching silence when the act is completed.

The Russian soldiers are not satisfied with mere sexual conquest. They are animals, biting away chunks of women’s breasts and cheeks and savagely mauling their genitals. Many strangle their victims after the act, silencing them forever. Perhaps they prefer murder to the personal shame of their victims glaring at them in hatred.

“I didn’t want to see because I couldn’t help them,” Helena remembers. “I was afraid they would rape my sister and me. No matter where we hid, they found our hiding places and raped some of my girlfriends.”

Russian soldiers raped millions of women during the course of the war.1 A large proportion of these women will contract venereal disease from their attackers. Some of them will commit suicide afterward. Others will become pregnant but refuse to carry a rapist’s baby to term and will find a way to abort the fetus. Many of those who give birth to these children of rape—Russenbabies, as they will be known—will abandon them. For some women, such as those in the barn, the liberation of Auschwitz was not the end of their suffering, but the beginning of a new kind of suffering.

“They did horrible things to them,” Helena will recount decades later, from her new home in the Jewish nation of Israel, the image of kicking, biting, and clawing at a young Soviet officer to prevent herself from becoming a victim of rape still clear in her head.

“Right up to the last minute we couldn’t believe that we were still meant to survive.”

* * *

Many Auschwitz survivors find there is no shelter, even when they make it back to their hometowns. All throughout Eastern Europe, Joseph Stalin and the Russian military machine have taken advantage of the mass Nazi deportations of Jews to steal homes and farms and give them to the Russian people. This is just the start of a massive forced migration that will see millions of non-Soviets in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Poland forced out of their homes. They will be left to resettle in the ruins of the Nazi occupation, in lands that will be without industry, farming, or infrastructure.

Like Helena and Rozinka Citrónóva, Linda Libusha is a Slovak who has survived Auschwitz. As she walks the streets of her beloved hometown of Stropkov, from where she was arrested and led away in March 1942, she believes the nightmare of the camps may be finally behind her.

But Linda doesn’t recognize anyone during her stroll down the main street. It’s as if everyone she ever knew has vanished. When she knocks at the door of the house in which she grew up, it is answered by someone she has never seen before, a heavyset man with a red Russian face. Over his shoulder she can see the same familiar rooms and hallways where she once played as a child—and where this foreigner now makes his home.

The Russian takes no pity on the death camp survivor.

“Go back where you came from,” he says, slamming the door in her face.

16

TRIER, GERMANY

MARCH 13, 1945

MORNING

George S. Patton is on the move.

Finally.

Sgt. John Mims drives Patton in his signature open-air jeep with its three-star flags over the wheel wells. The snows of the cruel subzero winter are melting at last. Patton and Mims pass the carcasses of cattle frozen legs-up as the road winds through Luxembourg and into Germany. Hulks of destroyed Sherman M-4s litter the countryside—so many tanks, in fact, that Patton makes a mental note to investigate which type of enemy round defeated each of them. This is Patton’s way of helping the U.S. Army build better armor for fighting the next inevitable war.

It is a conflict that Patton believes will be fought soon. The Russians are moving to forcibly spread communism throughout the world, and Patton knows it. “They are a scurvy race and simply savages,” he writes of the Russians in his journal. “We could beat the hell out of them.”

But that’s in the future, after Germany is defeated and the cruel task of dividing Europe among the victors takes center stage. For now, it is enough that the Third Army is advancing into Germany. Patton has sensed a weakness in the Wehrmacht lines and is eager to press his advantage.

It was four weeks ago, on February 10, when Dwight Eisenhower once again ordered Patton and his Third Army to stop their drive east and go on the defensive and selected British field marshal Bernard Law Montgomery to lead the massive Allied invasion force that will cross the strategically vital Rhine River. It is a politically astute maneuver, because while Montgomery officially reports to Eisenhower, the British field marshal believes himself to be—and is often portrayed in the British press as—Eisenhower’s equal. Winston Churchill publicly fueled this portrayal by promoting Montgomery to field marshal months before Eisenhower received his fifth star, meaning that for a time Montgomery outranked the supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe. Now Eisenhower’s decision to throw his support to Montgomery’s offensive neatly defuses any controversy that might have arisen over Eisenhower giving Patton the main thrust.

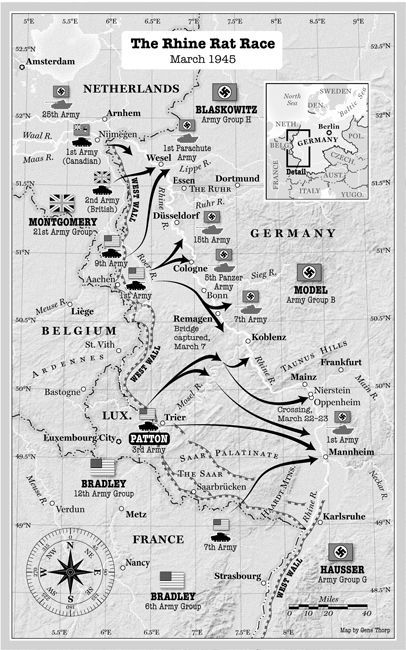

Stretching eight hundred miles down the length of Germany from the North Sea to Switzerland, the Rhine is the last great obstacle between the Allies and the German heartland. Whoever crosses it first might also soon know the glory of being the first Allied general to reach Berlin.

It is as if Patton’s monumental achievement at Bastogne never happened.

“It was rather amusing, though perhaps not flattering, to note that General Eisenhower never mentioned the Bastogne offensive,” he writes of his most recent discussions with Eisenhower. Then, referring to the emergency meeting in Verdun that turned the tide of the Battle of the Bulge, he adds, “Although this was the first time I had seen him since the nineteenth of December—when he seemed much pleased to have me at the critical point.”

Even more galling, not just to Patton but also to American soldiers, is that Montgomery has publicly taken credit for the Allied victory at the Battle of the Bulge. Monty insists that it is his British forces of the Twenty-First Army Group, not American GIs, who stopped the German advance.

“As soon as I saw what was happening,” Montgomery stated at a press conference, at which he wore an outlandish purple beret, “I took steps to ensure that the Germans would never get over the Meuse. I carried out certain movements to meet the threatened danger. I employed the whole power of the British group of armies.”

What Montgomery neglected to mention was that just three British divisions were made available for the battle. Of the 650,000 Allied soldiers who fought in the Battle of the Bulge, more than 600,000 were American. Once again, Bernard Law Montgomery used dishonest spin in an attempt to ensure his place in history.

Montgomery’s stunning January 7 press conference did considerable damage to Anglo-American relations.1 To Patton, it seems outrageous that Montgomery should be rewarded for such deceptive behavior.

Yet despite the fact that four American soldiers now serve along the German border for every British Tommy, Eisenhower has caved in to pressure from Churchill and selected Monty to lead the charge across the Rhine. Still, the reasons for this decision are practical as well as political: the crucial Ruhr industrial region is in northern Germany, as are Montgomery’s troops. Theoretically, Monty is capable of quickly laying waste to the lifeblood of Germany’s war machine.

Nevertheless, the decision makes George S. Patton furious.