General Bradley is surprised and distraught. As recently as last night, he was still telling an aide that the German offensive did not concern him.

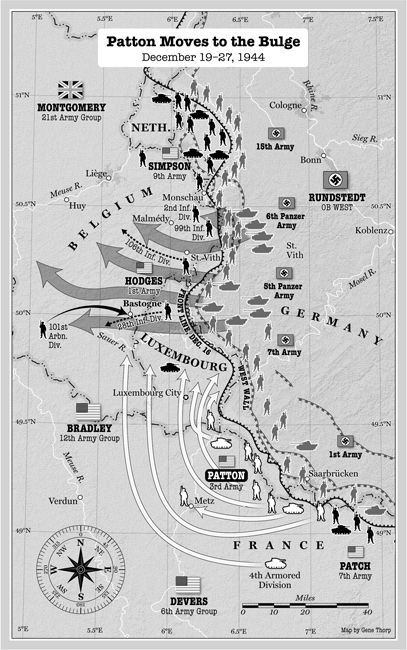

Bradley now looks like a fool. The German army has been decimating American forces for the last twelve hours. The situation has led Eisenhower to call an emergency meeting of the top Allied commanders. Patton’s Operation Tink is no more. As the irascible general predicted almost two weeks ago, Courtney Hodges and his First Army need to be rescued. And it is Patton’s Third Army that will have to do it.

* * *

“The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster,” Dwight Eisenhower tells the crowd of generals and senior officers seated at the long conference table. Ike will officially be promoted to five-star general tomorrow. But rather than looking elated, he is pale and tired. A glance around the dank second-floor room shows that British field marshal Bernard Law Montgomery is not in attendance.2 A situation map covers one wall. The air smells of Patton’s cigar, other officers’ cigarettes, wet wool, and wood smoke from the fire burning in a potbelly stove. The low flame fails to warm the room, meaning that almost no one has removed his thick overcoat.

Eisenhower continues, forcing a smile: “There will be only cheerful faces at the conference table.”

“Hell,” Patton interrupts, “let’s have the guts to let the sons of bitches go all the way to Paris. Then we’ll really cut them up and chew ’em up.”

Patton’s brash remark fails to get much more than a grim chuckle. But it sets a tone. As it was on the desperate battlefields of North Africa, Sicily, and France, Patton’s aggressiveness is once again vital to Allied success.

“George, that’s fine,” Eisenhower responds, once again reclaiming the room. “But the enemy must never be allowed to cross the Meuse.”

This is the line in the sand. Joachim Peiper and his SS Panzers are desperate to reach the Meuse River and secure its bridges in order to advance the German attack.

Eisenhower’s G-2 intelligence chief, the British major general Kenneth Strong, briefs the room on the current location of the American and German forces. Since late September, the German army has successfully prevented the U.S. and British forces from making any significant advances into the Fatherland. The war has become a stalemate. The Allies were foolishly assuming the Germans could never reverse the tide. That was a mistake.

If the seventeen divisions of German soldiers now marching through the Ardennes can somehow make it across the Meuse, the war could change radically—and not in the Allies’ favor.

“George,” Eisenhower states. “I want you to command this move—under Brad’s supervision, of course.” Here Eisenhower nods at Omar Bradley. Bad weather delayed Bradley on the long drive down from Luxembourg City, but he made it just in time. He is tense because he clearly was fooled by the enemy, and could be seen as to blame for the German advance. This is something no general can allow to happen in wartime.

Ike continues: “A counterattack with at least three divisions. When can you start?”

Patton is ready. He has not only come to the meeting equipped with three different battle plans, but he met earlier this morning with his staff and arranged a series of code words. Launching the Third Army’s attack is as simple as Patton calling his headquarters and saying the code for whichever of the battle plans is to be set into motion.

“As soon as you’re through with me,” Patton replies.

“When can you attack?” Eisenhower presses.

“The morning of December twenty-first,” Patton responds, referring to two days from now, “with three divisions,” he adds, still clutching his lighted cigar.

The room lapses into embarrassed silence. These career military officers know to be diplomatic when a man makes a fool of himself. And Patton has clearly crossed that line. Three divisions is not a small, nimble fighting force. It is a slow-moving colossus, spread out over miles of front lines. The idea that one hundred thousand men and supplies can somehow be uprooted and moved one hundred miles in forty-eight hours is ludicrous. If the men make it, but the guns and gasoline don’t, all will be lost. Attempting such a task in the dead of winter, on narrow and icy roads, borders on the impossible. Once again, Patton’s big mouth appears to be his undoing.

Eisenhower has seen this play out one too many times. “Don’t be fatuous, George.”

Patton looks to his deputy chief of staff, Lt. Col. Paul Harkins. Harkins says nothing, but nods, confirming that Patton is standing on solid ground.

“We can do that,” says Patton, staring straight into Eisenhower’s eyes.

Charles Codman, Patton’s aide-de-camp, will later write of “a stir, a shuffling of feet, as those present straightened up in their chairs. In some faces, skepticism. But through the room, the current of excitement leaped like a flame.”

Patton seizes the moment. Stepping to the map, he points out German weaknesses. This goes on for an hour. Omar Bradley says very little, realizing that this operation belongs to Patton and Patton alone.

Finally, as the meeting breaks up, Eisenhower jokes with his old friend. “Funny thing, George, every time I get a new star, I get attacked.”

“Yes,” Patton shoots back. “And every time you get attacked, I bail you out.”

* * *

This time, Patton might be too late.

Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe is already racing to the front lines. He is part of Dwight Eisenhower’s desperate effort to stem the German advance by throwing reserve troops into the fray. A career army officer, McAuliffe is a less-than-imposing physical specimen. He stands five feet, seven inches, and his slicked-back hair makes him look even shorter. McAuliffe is trying to reach the city of Werbomont, Belgium, before the Germans can capture it. But the journey is frustrating. Rather than speeding down icy roads, McAuliffe’s jeep is facing an onslaught of traffic.

Allied tanks, trucks, halftracks, and soldiers are all headed in the wrong direction—right into McAuliffe’s face.

They are not lost; they are defeated. They have done all they can to stop the German offensive, and their units have been decimated. They fought against hopeless odds to buy time for the 101st to get to Bastogne. Now they retreat from the front in droves. Their grimy, frostbitten faces are lined with grief after seeing their buddies blown to bits. The retreating men clog the narrow farm roads, utterly broken by the German advance. Never before has an American army been so devastated.

It does no good for McAuliffe’s driver to honk the horn or order a path cleared for the general. Most of the soldiers barely respond to anything. Some mumble lines of gibberish. Others are crying. Among these groups is the 110th Infantry, which has just lost 2,750 of their 3,200 men in battle. “They shambled along in shock and fear,” one eyewitness would later recall. “I have never seen such absolute terror in men.”

But McAuliffe can do nothing to halt the retreat. These men are not his concern. He has been ordered to the town of Werbomont, where he will lead the veteran 101st Airborne Division into battle. These hardened warriors now trail miles behind him aboard a ten-mile-long column of open-air cattle trucks.

The forty-six-year-old McAuliffe isn’t supposed to be in charge, but it seems that every man above him has taken Christmas leave—or, in the case of the division’s former chief of staff, shot himself. So McAuliffe rides hard for Werbomont. Rapid response is vital to stopping the Nazi penetration. In military terms, the blast hole that has been created in the Allied lines is known as a salient.

American newspapers are simply calling it “the Bulge.”