The Ardennes proves it. Totally off guard, Bradley has allowed a group of professional American baseball players to tour the area the Germans are now attacking.3 The alluring film actress Marlene Dietrich is also on hand. She has just finished performing in the Belgian crossroads town of Bastogne. Tonight she is scheduled to put on a show for the men of the Ninety-Ninth Division in the Belgian hamlet of Honsfeld.

That concert has been abruptly canceled.

* * *

The Ninety-Ninth Infantry Division of the American First Army is digging in, trying desperately to stop the elite Twelfth SS Panzer Division from capturing a spot on the map known as Elsenborn Ridge, a vast, treeless hill, beautiful in the summer when wild grasses cover its summit. But there is no beauty right now. Just frozen mud, corpses, and shell craters. Except for those moments when fog covers the hilltop or the powerful winds are driving rain and snow into their eyes—which is often—the men of the Ninety-Ninth have optimal fields of fire from their lazy semicircle of foxholes. Any German attack will require the enemy to cover a half mile of open ground, all while running uphill.

But one hundred yards down the slope, a thick forest offers the Germans complete concealment. The woods are dark and gloomy. A dense fog makes the Germans even less visible. The Ninety-Ninth are easy targets for the German artillery guns hidden in the forest below—including the high-velocity 88 mm guns, which fire a round that travels a half mile per second.

Many men in the Ninety-Ninth are new to combat and came to the Ardennes to ease into the frontline action. They lack winter-camouflaged uniforms, ammunition, and warm clothes, and yet they stand ready to hold the line at all costs.

Because if they don’t, Hitler’s crazy gamble in the Ardennes just might succeed.

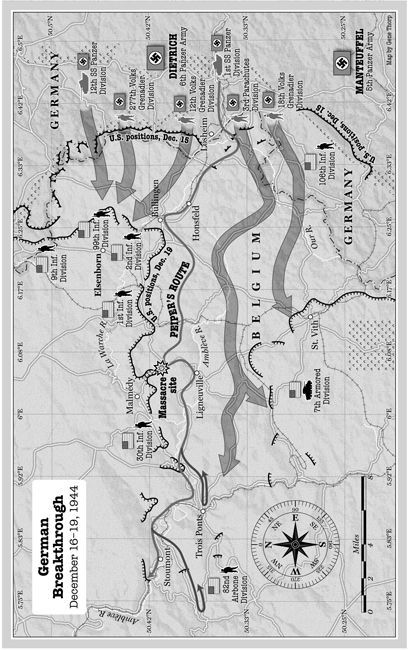

Like the equally strategic nearby location known as the Losheim Gap, the Elsenborn Ridge represents a vital corridor that the German army must possess in order for Operation Watch on the Rhine to be successful. The Losheim Gap is a narrow valley through which the Third Reich successfully invaded France in 1940, and is known to be the pathway for funneling tanks through the rugged Ardennes. The ridge is critical because a network of key roads lies on the other side. Capture the ridge, gain access to the roads, and the Twelfth Panzer Division suddenly stands a very good chance of making it all the way to Antwerp.

The Ninety-Ninth must hold the line.

Just yesterday they were thinking about Mel Ott, Marlene Dietrich, and Christmas. Many were even living in a warm barrack that had once belonged to the Germans, where they slept in beds and ate hot meals each morning and night.

Not today.

The Ninety-Ninth is made up of mostly green recruits who arrived in Europe just weeks ago. The unit was activated in October 1942, but many of those original members who trained together at Camp Van Dorn in Mississippi and Camp Maxey in Texas are either dead or in a hospital somewhere. Some units within the division are at half strength, meaning that cooks and clerks are now serving temporary duty as riflemen. The ground is almost frozen, but it is still possible to dig a deep foxhole, leaving the Ninety-Ninth less exposed and vulnerable. Their boots are not waterproof or insulated, so when they finally scrape away enough earth to make the home in the ground that will protect them from shrapnel and snipers, trench foot and frostbite add to their misery.

The German artillery and tanks fire from the safety of the valley forest, pounding the Ninety-Ninth as they huddle in their foxholes. The ground shakes so badly from the explosions that the few nearby trees fall over without being touched.

Snipers, meanwhile, kill anyone who exposes his head aboveground. And even when the Germans aren’t firing, the sounds of their laughter and snippets of conversation carry up the hill to the Ninety-Ninth. The Americans grow depressed and anxious as they hear the clank of tank treads from the forest, reminding them that the force now gathered below is, indeed, an enormous army.

It is only a matter of time before that army races up the Elsenborn Ridge to wipe out the Ninety-Ninth. The German forces outnumber the Americans by a ratio of five to one.

Those in the Ninety-Ninth who live to tell the story will long remember the scream of the high-velocity 88 mm shells, a sound that gets higher and more pronounced just before impact. They will remember reciting the Lord’s Prayer over and over as those assault guns pound their position. They will remember “the filth, the hunger, the cold, and the life of living like an animal.”

They abide by a new list of unwritten rules: They cannot sleep for any length of time because the German attacks have no set routine. They cannot leave their foxholes during daylight because German gunners zero in on any sign of movement.

Over the next four days, the Ninety-Ninth will see 133 more of its men die. Six hundred will fall back to the battalion aid stations to be treated for frozen feet. As many as 1,844 will go “missing,” meaning that their loved ones will never enjoy the closure that comes with having a body to bury. “This was our Valley Forge,” one soldier will remember.

Through it all, the leadership skills of the Ninety-Ninth’s officer corps will be sorely tested. Some will show themselves to be true leaders of men. Others will not. One senior officer will drive away in terror. Another will favor total surrender to fighting. After all, the Ninety-Ninth is facing elements of the Waffen SS, Hitler’s most elite and brutal fighting force. Surely it is better to raise the white flag of surrender and live to see home and family when the war ends than to face almost certain death or go “missing” at the hands of the SS.

It is Heinrich Himmler, the psychopathic leader of the SS, who preaches a philosophy that if an enemy is made to feel enough terror, there is no need for battle. He will simply quit.

But the Ninety-Ninth will soon learn that surrender does not always prevent violent death.

* * *

As the second day of Operation Watch on the Rhine begins, the First SS Panzer Division is on the move. They are the lead element in the much-larger Sixth Panzer Army, tasked with racing through the countryside to capture three vital bridges over the Meuse River.

The First comprises the best of the best, a fighting force so highly regarded by Hitler that he has allowed them to sew his name onto their uniform sleeves. In the buildup to Operation Watch on the Rhine, a lack of manpower was solved by shifting men from the Luftwaffe and German navy into the infantry. This is not the case with the First. They are all hardened fighters who have seen more than their share of combat in this war. And their armament bears testimony to their elite nature. It’s nothing but the finest for the First SS Panzer: sixty tanks, three flak tanks, seventy-five halftracks, fourteen 20 mm guns, twenty-seven 75 mm assault guns, and numerous 105 mm and 150 mm self-propelled howitzers.

“The morale was high throughout the entire period I was with them despite the extremely trying conditions,” an American officer will later write of his time as a prisoner of the First SS Panzer. “The discipline was very good. The physical condition of all personnel was good … The equipment was good and complete with the exception of some reconditioned half-tracks among the motorized equipment. All men wore practically new boots and had adequate clothing. Some of them wore parts of American uniforms, mainly the knit cap, gloves, sweaters, overshoes, and one or two overcoats. The relationship between officers and men … was closer and more friendly than I would have expected.”

In command of this magnificent fighting force is the dashing poster boy for the SS, twenty-nine-year-old Joachim Peiper. “He was approximately 5 feet 8 inches in height, 140 lbs. in weight, long dark hair combed straight back, straight well-shaped features with remarkable facial resemblance to the actor Ray Milland,” the American POW major will later write.