Patton has repaid Eisenhower’s largesse by enraging Russia, defying orders, instructing soldiers of the Third Army to steal gasoline and other supplies from other U.S. armies, and openly sulking when he is not allowed to do as he pleases. “I am not usually inclined to grumble or to think the cards are stacked against me,” Patton wrote to Beatrice during the Metz offensive, “but sometimes I wish that someone would get committed to do something for me.”

Still, Patton fights. And Patton wins. Army Air Corps general Jimmy Doolittle compared the relationship to that between a fighting dog and its master: “When Eisenhower releases Patton,” Doolittle notes, “it’s like releasing an English pit bull—once you let him go, it’s hard to make him stop.”

General George Patton confers with a lieutenant colonel near Sicily

What Eisenhower doesn’t know is that Adolf Hitler is furtively sending soldiers, tanks, and artillery toward a weakness in the American lines near the Ardennes Forest of Belgium. And that Operation Watch on the Rhine will utilize radio silence and deception in ways that will veil the attack from the Allied forces until it is far too late for them to effectively block it.

Eisenhower lives in the moment, trying to balance the many needs and demands of his lonely job. He has absolutely no idea how he will end the war by New Year’s Eve, but taking Aachen in Germany is certainly a good start.

The time once again to unleash his prize pit bull is about to arrive.

4

BOLSHOI THEATER

MOSCOW, RUSSIA

OCTOBER 14, 1944

7:00 P.M.

The houselights are up in Moscow’s legendary Bolshoi Theater as Olga Lepeshinskaya waits in the wings. The twenty-eight-year-old prima ballerina adjusts her costume and stretches her long, willowy legs as she prepares to take the stage. The acoustics in this legendary auditorium are among the best in the world, allowing Lepeshinskaya to hear with utter clarity the sounds of the last-minute tunings of violins and clarinets arising from the orchestra pit, and also vivid snippets of conversation from the 2,185 Russians noisily filing into their seats. She can hear their words of eagerness about enjoying this sold-out Saturday night performance, and the relief in their voices that after many hard-fought years the tide of war is turning in their favor.

Ever since Adolf Hitler ordered his armies to attack more than three years ago, the people of the Soviet Union—or Russia, as it is still commonly known—have seen more than ten million of their men and boys in uniform die. Amazingly, an equal number of civilians have also perished, done in by military bombardment, the random shooting of innocent women and children, and starvation. The German invaders cut off food supplies and appropriated harvests for themselves. Moving quickly and ruthlessly, the German war machine advanced a thousand miles from its own borders to the outskirts of Moscow before being repelled. At one point, German tanks and infantry stood just twenty-two miles from where these Muscovites sit right now.

But during the past six months, fate has turned against the German army. A summer offensive by Soviet forces pushed the Wehrmacht back. The long siege of Leningrad has come to an end, and just a few days ago that city was lit in the evening after three long years of blackouts. Truly, this is a night for all Russians to celebrate.

In keeping with the wartime austerity, the once-stately Bolshoi no longer sports gold leaf decorations. These have been painted over with a stark white paint, and the seats upholstered in plush crimson have been replaced by hard-backed chairs that not only fit more bodies into the ninety-year-old theater, but also make it possible to stage political rallies here in addition to the world’s finest ballets—thus, the countless hammer-and-sickle emblems lining the walls.

Olga Lepeshinskaya smiles as she peeks her head around the curtain to clandestinely observe the house. Tonight she will dance Giselle, in one of the most famous romantic roles in ballet. Just having a stage is a luxury, for as part of her wartime service Lepeshinskaya has performed in woods, meadows, and bombed-out churches to entertain the Soviet troops as part of the Bolshoi’s First Brigade frontline theater. Everything about the Bolshoi—the cavernous hall, the polished wood of the stage, and the many boxes lining the walls—feels like an extravagance after dancing in the dirt and rubble of the battlefield.

Suddenly a roar sweeps through the crowd. The audience turns and looks upward to the balcony that houses what was called the Imperial Box back before the days of Communist rule. A short, very overweight man bobs down toward his seat at the front of the box. The whole world knows the sight of Winston Churchill, prime minister of Great Britain. Why he happens to be in Moscow, attending the ballet, is a mystery to the crowd. But his presence here reinforces the solidarity between the Allied forces of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union. Together they will surely defeat Hitler and Germany.

The ovation is thunderous, and Churchill obliges the audience with a great wave of his hand before taking his seat.

As the house lights go down, Olga Lepeshinskaya gazes up at the box where Churchill sits. Her eyes study its other occupants, searching in vain for her lover. She sees American ambassador to the Soviet Union W. Averell Harriman; his young daughter, Kathleen; and Soviet diplomat Vyacheslav Molotov—but not the man she longs to see.

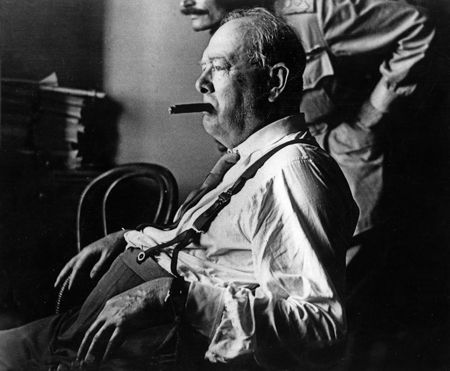

Winston Churchill watching a military operation through a window

Then: commotion. However, it is dark, and the blinding footlights obscure Olga’s view. What could be happening?

Twenty minutes later, as Lepeshinskaya’s flawless dancing once again proves that no one—perhaps with the possible exception of her nemesis, Galina Ulanova—deserves the title of prima ballerina more than she, a quick look up at Churchill’s box explains the source of the commotion.

For there, sitting next to Churchill, is the unmistakable profile of Olga Lepeshinskaya’s lover. He has not been to the ballet once since the war began. Iosif Vissarionovich’s face is pockmarked, his left arm shorter than the right, and he is the tiniest man in the box.1 Olga Lepeshinskaya does not call him Iosif, not even when they are alone. Instead, she knows him by his adopted name, the one that translates to “man of steel.”

Then, strangely, just before the end of the first act, Olga Lepeshinskaya is puzzled to see him move to the back of the box, where he cannot be seen.

When the first act of the ballet is complete, the houselights come back up, and the whole audience once again rises to its feet to give Churchill an ovation.

But the British leader refuses to bask in the acclaim alone. He beckons to the back of the box, encouraging another man to step forward.

So it is that Olga Lepeshinskaya’s lover appears and stands at Churchill’s right. The Soviet audience applauds thunderously, dazzled to see in the flesh the man whom they alternately love and fear.

All hail Marshal Joseph Stalin.

* * *

In his lifetime, Stalin will murder millions of people. Some will be shot, others will be denied food and ultimately die of starvation, millions will be sent to die in the deep winter snows of Siberia, and many will be tortured to death. Already, during one infamous murder spree in April and May of 1940, some twenty-two thousand Polish nationals were shot dead. What began as an attempt to execute every member of the Polish officer corps soon expanded to include police officers, landowners, intelligence agents, lawyers, and priests. The shootings were conducted for nights on end, often beginning at dusk and continuing until dawn. Some were mass killings carried out in the Katyn Forest, while others were individual executions inside the Kalinin and Kharkiv prisons. Mikhailovich Blokhin, chief executioner at Kalinin, personally shot seven thousand men in the back of the head as they knelt before him. Those killings took place inside a cell whose walls were lined with sandbags to deaden the sound. As soon as a victim fell dead, he was dragged from the room and thrown onto a truck for delivery to the burial site, while another handcuffed prisoner was marched before Blokhin and told to kneel. Noting that Russian pistols had so much recoil that his hand hurt after just a dozen killings, Blokhin opted for the smoother feel of the German Walther PPK.