Marshall is back in Washington, thirty-five hundred miles from the front. He is chief of staff of the army and chief military adviser to President Roosevelt. No other officer in the combined Allied armies has more power and influence than this lean, tough-talking Pennsylvanian.

Marshall’s return to the United States came after a weeklong tour of the European Theater of operations. Now he has cabled Eisenhower his great displeasure about the strategic situation. The “October Pause” that enrages George Patton infuriates Marshall, too. He is demanding an end to the stalemate. Everything possible must be done to attack deep into Germany and end the war by January 1.

Per Marshall’s orders, this is to include the use of weapons currently considered top secret, and the placement of every single available American, British, and Canadian soldier onto the front lines. Nothing must be held back.

Eisenhower must find a way. Orders are orders, and his success has been largely based on obeying them—unlike George Patton’s. So Ike smokes one cigarette after another. A few top American generals are coming over for dinner tonight. The celebration of the victory at Aachen can wait until then.

Across the hall, pale autumn light floods the glass-walled foyer, where a bronze bust of German air force commander Hermann Goering has been turned to face the wall. Eisenhower smokes another cigarette. He doesn’t have a favorite brand, and doesn’t know how many packs he smokes each day. The number is actually four, as evidenced by his yellow-stained fingertips and the nicotine stench from his trademark waist-length “Ike” jacket. His breath reeks of cigarettes and the countless pots of coffee he drinks each day.

Nicotine and caffeine are the only ways Eisenhower can manage the stress. He certainly can’t play golf in the midst of war. And right now, it’s still several hours too early for either a weak scotch and water, time alone in his upstairs apartment with a dime-store cowboy novel, or perhaps even a furtive romantic liaison with Kay Summersby, his personal chauffeur. At age thirty-six, the divorced Irish brunette who wears a captain’s rank has been assigned to Ike for two years.

At first she was merely his driver, a member of Britain’s all-volunteer Mechanised Transport Corps assigned to guide Eisenhower’s official Packard sedan through the blacked-out streets of London. Eisenhower admired her confidence behind the wheel and arranged for Summersby to be transferred permanently to the U.S. military’s Women’s Army Corps, where she was commissioned as an officer.

The turning point in their relationship came in June 1943, when the American colonel to whom Summersby was engaged got blown up by a land mine in Tunisia. It was Eisenhower who held Kay in his arms as she sobbed in grief. A spark passed between them in that moment, and the relationship deepened. Now the former fashion model has become Eisenhower’s chief confidante. She travels with him everywhere, and even sits in on high-level meetings, which makes her privy to top-secret war strategy. The two chatter and laugh constantly, passing the rare moments away from the pressure of the war by riding horses or playing bridge. Summersby has even gotten Eisenhower in the habit of taking tea each afternoon at 4:00 p.m., just like the British. He is so used to her constant presence that recently, while back in America for a short leave, Ike infuriated his wife, Mamie, by calling her “Kay” on two different occasions.

Kay Summersby

The close relationship between Summersby and Eisenhower goes on in secret—most of the time. But as John Thompson of the Chicago Tribune noted, their fondness for each other surfaces publicly now and then. “I have never before seen a chauffeur get out of a car and kiss the General good morning,” Thompson told American major general James M. Gavin when asked if the rumors were true.

No less than President Franklin Delano Roosevelt can see the sparks between Summersby and Ike. After the landmark Tehran Conference1 in 1943, FDR confided to his daughter, Anna, that he thought Eisenhower and his chauffeur were sleeping together.

In many ways, Eisenhower is a victim of his own success. Even though he has never once fought in battle, he has risen through the ranks and accrued power through intellect, shrewd diplomacy, and, most of all, finding ingenious ways of turning the outrageous demands of men such as George Marshall into reality.

The problem is his forces are as stuck and immobile now as they were a month ago. The shortage of gasoline, guns, and bullets that ground George S. Patton to a halt outside Metz still afflicts all the Allied forces up and down their five-hundred-mile front lines.

If there is one positive about the situation, it is that for the first time in ages, George S. Patton is not at the top of Eisenhower’s long list of problems in need of solving.

* * *

August 3, 1943, more than a year prior. Patton is visiting the Fifteenth Evacuation Hospital near the Sicilian city of Nicosia. He is exhausted after three straight weeks of managing the American attack on Italy, pushing his army past the unharvested fields of grain and the vineyards where ripened grapes dangle in enormous bunches. American and British forces are racing from the southern shores of Sicily to Messina, in the island’s north, where they hope to trap and capture the German army before its soldiers can flee to the Italian mainland. The fighting has been tough, with thousands killed on both sides. Patton’s army has captured more than twenty thousand German and Italian soldiers, as well as thousands of Sicilian peasants forced to fight for the Nazi cause. Always determined to win, Patton is more driven than ever because operational priority has been assigned to his archrival, British general Bernard Law Montgomery.2

Monty was given a plum landing spot in Sicily, on the coastal plains near Syracuse. British leadership, who had operational control of the battlefield, ordered Patton’s army to slug it out with the Axis defenders in the rugged Sicilian mountains.

This, Patton cannot allow. Nor can he stand to hear any more British gossip about Americans being inferior soldiers. He is determined to beat Monty into Messina and win glory for his army, despite the obstacles thrown in his way. “This is a horse race in which the prestige of the U.S. Army is at stake. We must take Messina before the British,” he writes to one of his commanding generals. “Please use your best efforts to facilitate the success of our race.”

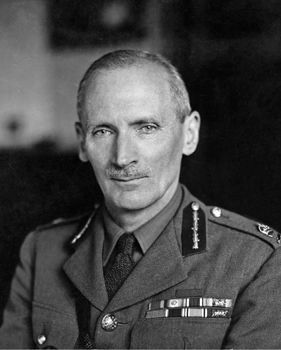

General Bernard Law Montgomery

The end of the race is still two weeks away as Patton visits a small field hospital in the crags of Sicily’s central highlands. His love of the fighting man is profound, and extends to the aftermath of battle, where he is fond of personally presenting the wounded with their Purple Heart, a medal that recognizes injury during the course of combat.

The air smells of antiseptic and dust. Men lie on litters and improvised beds, their eyes glassy from sedatives. Many have their hands, faces, and torsos wrapped in gauze, speckled here and there with blood that has soaked through the dressings. Nurses and doctors weave through this sea of men, managing their pain the best they can before determining who will be sent back to the front and who will be transferred to a hospital far behind the lines for further treatment. “All,” Patton will write in his journal tonight, “were brave and cheerful.”

Except one soldier.

Pvt. Charles H. Kuhl of the First Infantry Division sits on the edge of a stool. He is being treated for exhaustion and anxiety. This is his third trip to a field hospital for this diagnosis in his eight short months in the army.