Q: How long did you plan the escape?

A: Two or three days previous.

Q: Do you wish to say anything for yourself?

A: No, sir.

Mr. Miller: After question you, Walters, I recommend that you forfeit 3100 days Statutory Good Time.

Walter was immediately brought to D Block and placed into the strip-cell, where he remained until August 28, 1943, when he was placed in segregation. He would again be placed in an isolation cell in May of 1944, after officers found a six-inch hacksaw blade hidden beneath the linoleum flooring of his D-Block cell (#23). He would ultimately remain in segregation until May 10, 1945, and then as surprising as it may seem, he was released back into the general population and given a work assignment back in the prison laundry.

Despite his years in segregation, little had changed in Walters’ attitude toward the administration. He continued to receive write-ups, which described him as making threats against officers, claiming that they made too much noise when opening the cells of the kitchen workers in the early morning. He also was reported for being intoxicated on homemade brew. In what could probably be considered one of the more unusual write-ups for possession of contraband on Alcatraz, Walters was also sent to isolation for having a toy rubber duck hidden in his cell in April of 1949.

Walter was released from Alcatraz and returned to Leavenworth on August 23, 1952. His admission record at Leavenworth certainly offered a profile of an inmate who had failed to make a positive adjustment on the Rock. It read:

At Alcatraz, he was reported for fighting, refusing to work, insolence, possession of a contraband knife, assaulting another inmate with a knife, attempting to smuggle food form the dining room, wasting food, attempting to escape, creating a disturbance and using profanity, fighting and having part of a band saw in his cell, refusing to do work directed, inciting a riot, interfering with the count and intoxication.

At Leavenworth Walters would be assigned to the Shoe Factory, and he was said to make an excellent adjustment following his transfer. He was paroled and returned to Dallas in 1958, and then he married only a year after his release. He found a job working in a small bakery and for a short period his life seemed normal. It wasn’t anything remotely like what he had experienced sitting in solitary cell at Alcatraz. But in spite of his recently won freedom and his new wife, he continued to struggle with his past. He would eventually revert back to his old familiar life as an outlaw.

Walter’s final brush with the law would occur on October 13, 1971. At about 10:00 a.m., he and an unidentified female passenger were pulled over on a routine traffic stop in Euless, Texas. As Texas Ranger Bill Harvell approached the passenger side of the vehicle, Walters drew a pistol. Harvell was able to retreat to the rear of the vehicle, when Walters punched the accelerator to flee the scene. Harvell opened fire on the 1962 Plymouth Valiant with his service revolver, emptying the entire chamber. Harvell then returned to his patrol car and gave chase, while summoning other law enforcement officers on the radio.

Walters sped through a residential district, stopping only briefly to release his female passenger. Carrying his pistol and a sawed-off shotgun, he then took off on foot into a remote pasture. An intensive manhunt ensued and Walters stayed ahead of the police for a short time. At daybreak, Hoyt Houston of Bedford, Texas, entered his garage to find Walters sleeping there in a small fishing boat. Walters ordered the man into his house at gunpoint and took his family hostage. Hoyt had two young daughters and one had been able to escape through her bedroom window to run and get help.

When the police arrived at the Houstons’ home, Walters aimed his shotgun at the family and demanded that the police drop their weapons. He then forced his hostages into the family’s 1969 Mercury and directed Mrs. Houston to drive while he kept his loaded shotgun aimed at the head of her husband, who was sitting in the passenger seat. After a slow and careful pursuit, the police were able to force the vehicle to stop on a bridge just outside of Grapevine, Texas. A police car had been positioned at the end of the small overpass, creating a roadblock. While police attempted to negotiate the safe release of the Houston family, a Texas Ranger named Tom Arnold took aim at Walters through the target scope of his 30-06 rifle. During a brief moment when approaching officers distracted Walters, Tom Arnold fired a fatal shot at Walters’ head. As the window shattered, Arnold dropped his rifle and aimed his pistol steadily at the slumped figure, then fired several more rounds into Walters’ body. None of the Houston family members were injured in the hail of gunfire. Ironically, Walters died only 300 feet from where Bonnie and Clyde had slain two police officers on April 1, 1934.

ESCAPE ATTEMPT #9

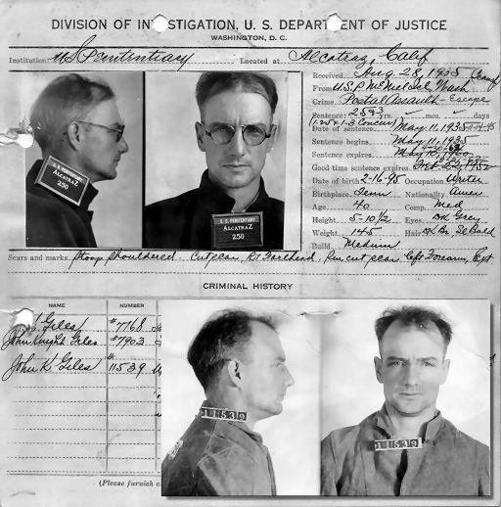

Date:

July 31, 1945

Inmates:

John Giles

Location:

Dock Area

John Knight Giles

John Giles was described by Warden Johnston as a deep and quiet gentleman with a lone wolf personality and someone who was difficult to figure out. While his attempted escape is not remembered as the most famous, it certainly was known in the circles of Alcatraz as one of the most ingenious escapes ever attempted at the Rock. John Knight Giles was born in Elgin, Tennessee on February 16, 1895 to a local engineer, as the youngest of three boys. His father had migrated south from New York and his mother was from Georgia, and the couple apparently separated frequently throughout their marriage. It is documented that John’s mother suffered from mental illness and was admitted to mental institutions several times during his childhood. John attended high school in Everett, Washington, and for unknown reasons he decided to quit school at age fifteen. He took a job as a Surveyor’s Assistant in the U.S. Reclamation Service near British Columbia, where he worked for almost four years.

Giles first brush with the world of crime came in 1915, when he was given a five to ten year sentence for robbery and was incarcerated at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. It would appear that officials were lenient with Giles and he was issued a pardon in 1918, probably to allow him to enter the U.S. Army for the First World War. He failed to enlist and only months after his release he committed another robbery. In November of 1918 Giles planned what he thought would be an easy burglary, targeting an interstate bridge tender in the state of Oregon. He robbed the tender at gunpoint and then attempted a getaway. He was swiftly apprehended by Deputy Sheriff Frank W. Twombley, and during the arrest, the officer was killed. An all-points bulletin was issued on Giles, and he was quickly taken into custody.

Giles was convicted of murder, and sentenced to life in prison at the State Penitentiary in Salem, Oregon. He was considered a quiet inmate, and he took to writing short fictional stories. Records show that he was somewhat successful in selling his work, and wrote for a variety of pulp magazines. After serving several years, Giles would boast to officials that he had helped to prevent riots and other uprisings by acting as a leader among the inmates. In November of 1934, after sixteen uneventful years, Giles managed to escape from the State Penitentiary. He was later identified in connection with a theft in Redding California, but managed to elude officials for over a year, always keeping one step ahead of them. However Giles would soon participate in a crime that would finally seal his fate.