While Socrates frantically paced, Levin addressed Stepan Arkadyich, who was smoking serenely.

“Was ever a man in such a fearful fool’s position?” he said.

“Yes, it is stupid, and I feel awful,” Stepan Arkadyich assented, smiling soothingly. “I’m a simple block of wood without my Little Samovar. But don’t worry, it’ll be brought directly.”

“No, what is to be done!” said Levin, with smothered fury. “What if it’s been lost?”

“It’s not been lost,” reassured Stepan Arkadyich.

“It may have been lost. Yes, probably it’s lost,” intoned Socrates.

“That is not helpful,” said Stepan Arkadyich with a glare suggesting a wish that Socrates, too, were in a Vladivostok R.P.F. Addressing himself to Levin, he said: “Just wait a bit! It will come round.”

And so while the bridegroom was expected at the church, he was pacing about his room like a caged Huntbear, peeping out into the corridor, and with horror and despair recalling what absurd things he had said to Kitty and what she might be thinking now.

At last the II/Runner/470 zipped into the room with the shirt held aloft from a pincer, like a dog with a bagged quail. Three minutes later Levin ran full speed into the corridor not looking at his I/Hourprotector/8 for fear of aggravating his sufferings.

“It’s eleven thirty…,” moaned Socrates, motoring quickly behind him. “eleven thirty-one! We are very late, very late indeed!”

“Not helpful,” sighed Stepan Arkadyich as he tossed his cigarette into an ashtray, where it sputtered, hissed, and disappeared. “Not helpful at all.”

CHAPTER 3

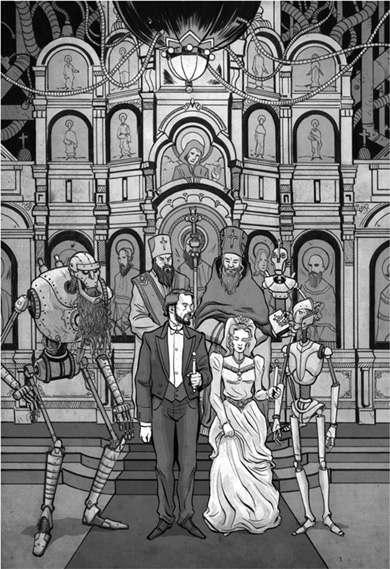

“THEY’VE COME!” “Here he is!” “Which one? The tall yellow robot?” “No, fool! The robot’s master!” “Rather young, eh?” were the comments in the crowd, when Levin at last walked with Socrates into the church.

Stepan Arkadyich told his wife the cause of the delay, and the guests were whispering it with smiles to one another. Levin saw nothing and no one; he did not take his eyes off his bride as she walked up the aisle toward him.

Everyone said she had lost her looks dreadfully of late, and was not nearly so pretty on her wedding day as usual; but Levin did not think so. He looked at her hair done up high, with the long white veil and white flowers and the high, stand-up, scalloped collar, her strikingly slender figure, and it seemed to him that she looked better than ever-not because her beauty was accented by these flowers, this veil, this gown from Paris, and by the gentle pink backlight shed by Tatiana-but because, in spite of the elaborate sumptuousness of her attire, the expression of her sweet face, of her eyes, of her lips was still her own characteristic expression of guileless truthfulness.

“I was beginning to think you meant to run away,” she said, and smiled at him.

“It’s so stupid, what happened to me, I’m ashamed to speak of it!” he said, reddening.

Dolly came up, tried to say something, but could not speak, cried, and then laughed unnaturally. She was more affected than she had anticipated by the absence of Dolichka. How perfectly ridiculous, she thought, to have no nimble metal fingers to hand her tissues, no strong metal shoulder to lean on, at her own sister’s wedding!

Kitty looked at her, and at all the guests, with the same absent eyes as Levin.

Meanwhile the officiating clergy had gotten into their vestments, and the priest and deacon came out to the lectern, which stood in the forepart of the church. The priest turned to Levin saying something, but it was a long while before Levin could make out what was expected of him. For a long time they tried to set him right and made him begin again-because he kept taking Kitty by the wrong arm or with the wrong arm-till he understood at last that what he had to do was, without changing his position, to take her right hand in his right hand. When at last he had taken the bride’s hand in the correct way, the priest walked a few paces in front of them and stopped at the lectern. The crowd of friends and relations moved after them, with a buzz of talk and a rustle of skirts. Someone stooped down and pulled out the bride’s train. The church became so still that one could hear the faint buzz of the I/Lumiére/7s in their sconces.

All eyes were fixed upon the altar, and no one noticed that outside the church, the II/Policeman/56s were motoring in arbitrary circles, periodically colliding harmlessly, a sure sign of having been severely, and purposefully, maltuned.

The little old priest in his ecclesiastical cap, with his long, silverygray locks of hair parted behind his ears, was fumbling with something at the lectern. “Drat it, Saint Peter, where’d’ya keep the things?” he muttered in frustration; but while the church’s sacramental robot had been permitted to remain in its place at the altar, its analytical core had been removed for the Ministry’s adjustment. At last the priest put out his little old hands from under the heavy silver vestment with the gold cross on the back of it.

“A GIRL CANNOT BE WED WITHOUT THE SOOTHFUL PRESENCE OF HER CLASS III,” THE PRINCE HAD PLEADED

The priest initiated two I/Lumiére/7s, wreathed with flowers, and faced the bridal pair. He looked with weary and melancholy eyes at the bride and bridegroom, sighed, and putting his right hand out from his vestment, blessed the bridegroom with it, and also with a shade of solicitous tenderness laid the crossed fingers on the bowed head of Kitty. Then he gave them the lumiéres, and taking the censer, moved slowly away from them.

“Can it be true?” thought Levin, and he looked round at his bride. Looking down at her he saw her face in profile, and from the scarcely perceptible quiver of her lips and eyelashes he knew she was aware of his eyes upon her.

She did not look round, but the high, scalloped collar, which reached her little pink ear, trembled faintly. He saw that a sigh was held back in her throat, and the little hand in the long glove shook as it held the thin illuminated Class I.

All the fuss of the shirt, of being late, all the talk of friends and relations, their annoyance, his ludicrous position-all suddenly passed away and he was filled with joy and dread.

It was that precise cocktail of strong feeling that triggered the first of the emotion bombs.

It exploded with pinpoint precision beneath the seat of a single parishioner, an elderly second cousin of Kitty’s seated in the third pew from the back. The blast unleashed all the destructive force of a traditional explosion, but all concentrated on this one unfortunate soul, furiously vibrating every molecule in his body and turning his insides to a gelatinous paste. So precise was this terrible blast of force, however, that even the parishioners to the left and right of the man did not realize what had transpired, that the wedding was suddenly under attack by agents of UnConSciya. The wedding guest simply slumped forward in his seat, and might have been sleeping: an impolite but hardly shocking action by an elderly man at a church service.

“Blessed be the name of the Lord,” the solemn syllables rang out slowly one after another, as the priest intoned the liturgy, setting the air quivering with waves of sound. The brains of the murdered second cousin, essentially turned to liquid, leaked slowly from his ears.

“Blessed is the name of our God, from the beginning, is now, and ever shall be,” the little old priest said in a submissive, piping voice, still fingering something at the lectern. And the full chorus of the unseen choir rose up, filling the whole church, from the windows to the vaulted roof, drowning out a lone woman’s panicked shrieking from the back of the church.

“This man is dead! My God, what has-what’s happened?!”