‘ “Protect it with your life”,’ Jacob mutters under his breath…

… which is, he thinks, the crux of my dilemma.

Ten days ago, the Shenandoah anchored off Papenburg Rock – named for martyrs of the True Faith thrown from its heights – and Captain Lacy ordered all Christian artefacts placed in a barrel to be nailed shut, surrendered to the Japanese and returned only when the brig departed from Japan. Not even Chief-Elect Vorstenbosch and his protégé clerk were exempt. The Shenandoah’s sailors grumbled that they’d sooner surrender their testicles than their crucifixes, but their crosses and St Christophers did vanish into hidden nooks when the Japanese inspectors and well-armed guards carried out their search of the decks. The barrel was filled with an assortment of rosary beads and prayer books brought by Captain Lacy for this purpose: the de Zoet Psalter was not amongst them.

How could I betray my uncle, he frets, my Church and my God?

It is buried amidst his other books in the sea-chest on which he sits.

The risks, he assures himself, cannot be so very great… There is no marking or illustration by which the Psalter could be identified as a Christian text, and the interpreters’ Dutch is too poor, surely, to recognise antique Biblical language. I am an officer of the Dutch East Indies Company, Jacob reasons. What is the worst punishment the Japanese could inflict on me?

Jacob doesn’t know, and the truth is that Jacob is afraid.

A quarter-hour passes; of Chief Vorstenbosch or his two Malays there is no sign.

Jacob’s pale and freckled skin is frying like bacon.

A flying fish scissors and skims itself over the water.

‘Tobiuo!’ one oarsman says to the other, pointing. ‘Tobiuo!’

Jacob repeats the word and both oarsmen laugh until the boat rocks.

Their passenger doesn’t mind. He watches the guard-boats, circling the Shenandoah; the fishing skips; a coast-hugging Japanese cargo ship, stocky as a Portuguese carrack but fatter-bellied; an aristocratic pleasure-craft, accompanied by several attendant vessels, draped with the ducal black-on-sky-blue colours; and a beak-prowed junk, similar to those of the Chinese merchants of Batavia…

Nagasaki itself, wood-grey and mud-brown, looks oozed from between the verdant mountains’ splayed toes. The smells of seaweed, effluence and smoke from countless flues are carried over the water. The mountains are terraced by rice paddies nearly up to their serrated summits.

A madman, Jacob supposes, might imagine himself in a half-cracked jade bowl.

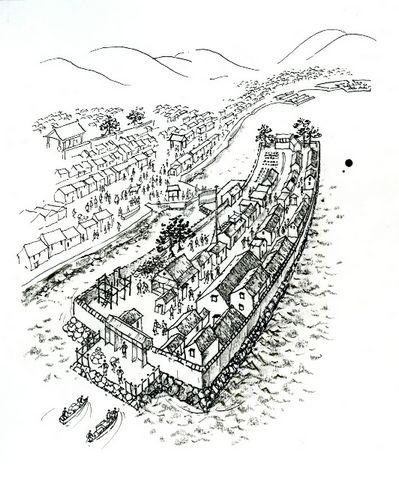

Dominating the shorefront is his home for the next year: Dejima, a high-walled, fan-shaped artificial island, some two hundred paces along its outer curve, Jacob estimates, by eighty paces deep, and erected, like much of Amsterdam, on sunken piles. Sketching the trading factory from the Shenandoah’s foremast during the week gone, he counted some twenty-five roofs: the numbered warehouses of Japanese merchants; the Chief’s and the Captain’s Residences; the Deputy’s House, on whose roof perches the Watchtower; the Guild of Interpreters; a small hospital. Of the four Dutch warehouses, the Roos, the Lelie, the Doorn and the Eik, only the last two survived what Vorstenbosch is calling ‘Snitker’s Fire’. Warehouse Lelie is being rebuilt, but the incinerated Roos must wait until the factory’s debts are in better order. The Land-Gate connects Dejima to the shore by a single-span stone bridge over a moat of tidal mud; the Sea-Gate, at the top of a short ramp where the Company sampans are loaded and unloaded, is opened only during the trading season. Attached is a Customs House, where all Dutchmen except the Chief Resident and the Captain are searched for prohibited items.

A list at whose head, Jacob thinks, is ‘Christian Artefacts’…

He turns to his sketch and sets about shading the sea with charcoal.

Curious, the oarsmen lean over; Jacob shows them the page:

The older oarsman makes a face to say, Not bad.

A shout from a guard-boat startles the pair: they return to their posts.

The sampan rocks under Vorstenbosch’s weight: he is a lean man, but today his silk surtout bulges with sections of ‘unicorn’ or narwhal horn, valued in Japan as a powdered cure-all. ‘It is this buffoonery’ – the incoming Chief raps his knuckles on his garment’s sewn-in bumps – ‘that I intend to eradicate. “Why,” I demanded of that serpent Kobayashi, “not simply have the cargo placed in a box, legitimately; rowed across, legitimately; and sold at private auction, legitimately?” His reply? “There is no precedent.” I put it to him, “Then why not create a precedent?” He stared at me as if I’d claimed paternity of his children.’

‘Sir?’ the First Mate calls. ‘Shall your slaves accompany you ashore?’

‘Send them with the cow. Snitker’s Black shall serve me meanwhile.’

‘Very good, sir; and Interpreter Sekita begs a ride ashore.’

‘Let the mooncalf down, then, Mr Wiskerke…’

Sekita’s ample rear juts over the bulwark. His scabbard catches in the ladder: his attendant earns a sharp slap for this mishap. Once the master and servant are safely seated, Vorstenbosch doffs his smart tricorn hat. ‘A divine morning, Mr Sekita, is it not?’

‘Ah.’ Sekita nods without understanding. ‘We Japanese, an island race…’

‘Indeed, sir. Sea in all directions; deep blue expanses of it.’

Sekita recites another rote-learnt sentence: ‘Tall pines are deep roots.’

‘For why must we waste our scant monies on your obese salary?’

Sekita purses his lips as if in thought. ‘How do you do, sir?’

If he inspects my books, thinks Jacob, all my worries are for nothing.

Vorstenbosch orders the oarsmen ‘Go!’ and points to Dejima.

Unnecessarily and unasked, Sekita translates the order.

The oarsmen propel the sampan by ‘sweeping’ their oars in the manner of a water-snake, in time to a breathy shanty.

‘Might they be singing,’ wonders Vorstenbosch, ‘ “Give Us Your Gold, O Stinking Dutchman”?’

‘One trusts not, sir, in the presence of an interpreter.’

‘That’s a charitable description of the man. Yet better him than Kobayashi: this may be our last chance to have a private discussion for a little while. Once ashore, my priority must be to ensure as profitable a trading season as our shoddy cargo can afford. Yours, de Zoet, is quite different: piece together the factory accounts, both for Company trade and private trade since the year ’ninety-four. Without knowing what the officers have bought, sold and exported and for how much, we cannot know the full extent of the corruption we must deal with.’

‘I’ll do my very best, sir.’

‘Snitker’s incarceration is my statement of intent, but should we mete out the same treatment to every smuggler on Dejima, there would be nobody left but the two of us. Rather, we must show how honest labour is rewarded with advancement, and theft punished with disgrace and gaol. Thus, only thus, may we clean out this Augean stable. Ah, and here is van Cleef, come to greet us.’

The acting deputy walks down the ramp from the Sea-Gate.

‘ “Every Arrival,” ’ quotes Vorstenbosch, ‘ “is a Particular Death.” ’

Deputy Melchior van Cleef, born in Utrecht forty years ago, doffs his hat. His swarthy face is bearded and piratical; a friend might describe his narrow eyes as ‘observant’, an enemy as ‘Mephistophelian’. ‘Good morning, Mr Vorstenbosch; and welcome to Dejima, Mr de Zoet.’ His handshake could crush stones. ‘To wish you a “pleasant” stay is overly hopeful…’ He notices the fresh kink in Jacob’s nose.

‘I am obliged, Deputy van Cleef.’ Solid ground sways under Jacob’s sea-legs. Coolies are already unloading his sea-chest and carrying it to the Sea-Gate. ‘Sir, I should prefer to keep my luggage in sight…’